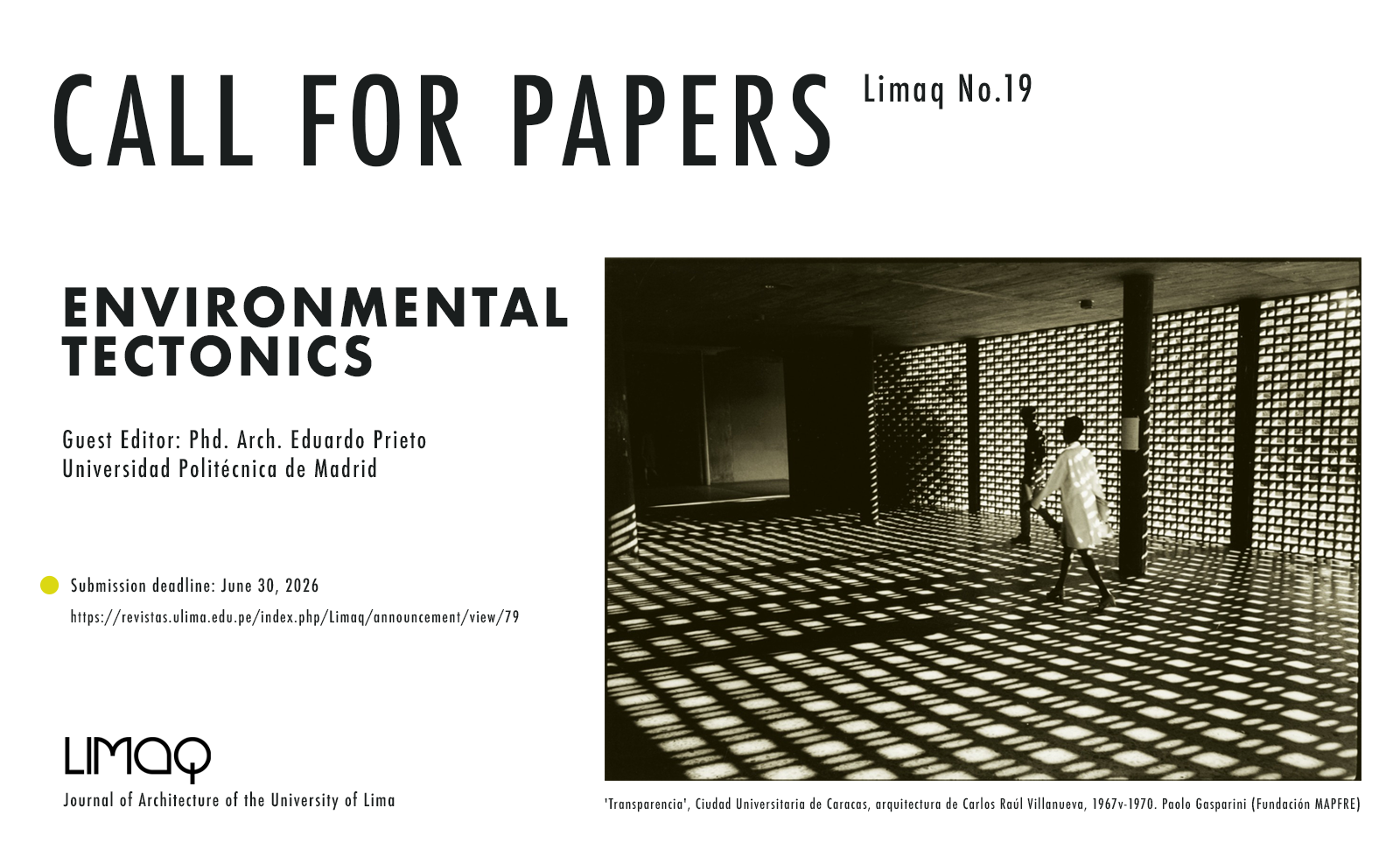

Thematic Call: “Environmental Tectonics”

Submission deadline: June 30, 2026 – Limaq No. 19

Submission deadline: June 30, 2026 – Limaq No. 19

Thematic section: “Environmental Tectonics”

Guest Editor: Phd. Arch. Eduardo Prieto

Universidad Politécnica de Madrid

The assembling of pieces skillfully resolved by the cabinetmaker, the mounting of structures deftly arranged by the shipbuilder, the primordial construction raised with spontaneous wisdom by birds in their nests… For centuries, the word “tectonics” denoted the act of building in general; it was Gottfried Semper who endowed the term with its disciplinary connotation, before the avant-gardes came to prefer words such as Bau or Construction, better aligned with the interested discourse of the technological Zeitgeist, and before, with the post–postmodern “return to order,” Kenneth Frampton once again vindicated the term in a simultaneously novel and traditional transversal and aesthetic sense through his Tectonic Culture. Since then, “tectonics” has lived in a state of semantic calm that is, however, only apparent, given the profound transformations currently affecting techniques and materials, as well as the no less profound economic, social, and political changes that today shape the construction system.

Among these changes, the most influential in shaping imaginaries and techniques has been the emergence of the new paradigm of sustainability, which combines moral pragmatism, social awareness, and economic opportunism, and maintains a complex relationship with technology. Indeed, within the peculiar intellectual framework of “the sustainable,” technology can be both a redemptive entity and the beast responsible for all evils. This complex—at times contradictory—relationship is having a direct impact on architecture, which perhaps for the first time since the heroic days of postmodernity and semiotics seems to be rethinking its fundamental premises through new frameworks of discussion. These diverse frameworks give rise to the questions posed by this call: Do the meanings traditionally ascribed to the word “tectonics” still hold, or is it necessary to expand the concept toward a kind of “environmental tectonics”? If so, what would its attributes, singularities, and paradoxes be? Would environmental tectonics have specific formal and aesthetic manifestations, or would it merely coexist with the modes or “styles” of traditional registers? In parallel: Would it serve only the pragmatic aims of sustainability, or would it fertilize architecture with new cultural and aesthetic imaginaries? Would it present itself as a novel, disruptive, avant-garde tectonics (one more in the history of the last century), or would it be able to establish a certain interested and operative relationship with tradition, with history? Finally: Would this environmental tectonics consist merely in the technical validation of the normative, social, and economic demands of sustainability, or would it have—or could it have—a critical, even resistant character, somehow encouraging the renewal of architecture?

As a place where climates and microclimates, techniques and ideologies converge, architecture can become a powerful field of technical, compositional, pedagogical, social, and even political experimentation regarding our ecological and social practices, in light of the environmental tectonics proposed here. Delimiting this field is the aim of this call, which seeks less to receive proposals to “save the world” than to critically enrich architecture within the multicritical context in which we are compelled to live.

.jpg)