The Keys to 360º Narrative Through a Study

of the RTVE Broadcast of the Goya Awards

Raquel Caerols Mateo**

Universidad Complutense de Madrid, España

Manuel Gerardo Casal Balbuena***

Universidad Francisco de Vitoria, España

Pablo Garrido Pintado****

Universidad Complutense de Madrid, España

Received: November 12, 2022 / Accepted: March 16, 2023

doi: https://doi.org/10.26439/contratexto2023.n39.61376322

ABSTRACT. The push to make use of 360o narratives is driven from the growing popularity of the phenomenon in the media, especially since 2015. In Spain, the LAB of Radio Televisión Española (RTVE) has been experimenting with this technology, offering recordings of shows and documentaries and pioneering the recording of an interactive virtual reality episode of a television series. In order to identify the characteristics, challenges and difficulties of broadcasting 360o events, this paper takes as a case study the broadcast of the Goya Awards Ceremony on RTVE. The Goya Awards are a live event where the leading figures of Spanish cinema are recognised for their work during the previous year. This study is based on a prior interview with two producers from RTVE LAB responsible for the 360o production of the event. Based on the interview, a content analysis model was designed and applied to a fragment of the production.

From this analysis it can be deduced that, despite shared aspects of traditional and 360o broadcasts, there are marked differences between these types of narratives, the one designed to be watched (traditional) and other to be experienced (360o). The coexistence between these two ecosystems is difficult but not impossible as both share many parameters related to the production of meaning. The paper highlights the need standardise 360o technology for a satisfying first-person experience and acclimatisation on the part of the spectator-user

Claves de la narrativa 360o a través del estudio de la retransmisión

de la gala de los Premios Goya en RTVE

RESUMEN. El empuje del uso de narrativas 360o es un fenómeno que se viene popularizando en redes, especialmente, desde el 2015. En España, el Laboratorio de Innovación Audiovisual de Radio y Televisión Española (Lab RTVE) ha experimentado con esta tecnología ofreciendo grabaciones de espectáculos y documentales, y al ser pioneros en la grabación del primer episodio de realidad virtual interactiva de una serie de televisión. Con objeto de conocer las características, retos y dificultades de la retransmisión de eventos en 360o, el presente trabajo toma como caso de estudio la retransmisión de la gala de los Premios Goya en RTVE. Se trata de un evento en directo donde se premia a los personajes más destacados del cine español durante el año anterior. El método escogido parte de una entrevista previa a dos responsables del Lab RTVE encargados de la realización 360o de la gala. A partir de los datos recabados en la entrevista se diseñó un modelo de análisis de contenido aplicado a un fragmento de la producción. Del análisis realizado se deduce que, pese a que la retransmisión tradicional y 360o comparten aspectos formales, existen unas marcadas diferencias entre las narrativas. Unas diseñadas para ser visionadas (narrativa tradicional) y otras para ser experimentadas (narrativa 360o). La convivencia entre ambos ecosistemas sígnicos se presenta difícil, pero no imposible, ya que ambos tipos de realización comparten muchos parámetros relativos a la producción de significado. Asimismo, se ve necesaria una estandarización de la tecnología 360o para una vivencia satisfactoria en primera persona y una aclimatación por parte del espectador-usuario.

PALABRAS CLAVE: panorama / narrativas 360o / narrativa inmersiva / Lab RTVE / los Premios Goya

CHAVES PARA A NARRATIVA 360º A TRAVÉS DO ESTUDO DA TRANSMISSÃO

DA GALA DOS PRÉMIOS GOYA NA RTVE

RESUMO. O impulso para o uso de narrativas 360º vem da popularização do fenômeno em redes, especialmente desde 2015. Na Espanha, o Lab de Radio y Televisión Española vem experimentando esta tecnologia, oferecendo gravações de programas e documentários e sendo pioneiro na gravação do primeiro episódio interativo de realidade virtual de uma série de televisão. Para conhecer as características, desafios e dificuldades da transmissão de eventos 360º, este artigo toma como estudo de caso a transmissão da Gala do Goya Awards na RTVE. Este é um evento ao vivo onde as figuras mais destacadas do cinema espanhol durante o ano anterior são premiadas. O método escolhido é baseado em uma entrevista prévia com duas pessoas responsáveis pelo RTVE Lab, que são responsáveis pela produção 360º da gala. Com base nos dados coletados na entrevista, um modelo de análise de conteúdo foi projetado e aplicado a um fragmento da produção. Da análise realizada, pode-se deduzir que, apesar de as transmissões tradicionais e 360º compartilharem aspectos formais, existem diferenças marcantes entre as narrativas. Algumas são projetadas para serem assistidas (tradicionais) e outras para serem vivenciadas (360º). A coexistência entre os dois ecossistemas signos é difícil mas não impossível, já que ambos os tipos de produção compartilham muitos parâmetros relacionados com a produção de sentido. Também é necessário padronizar a tecnologia 360º para uma experiência satisfatória na primeira pessoa e aclimatação por parte do espectador-usuário.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: panorama / narrativas 360º / narrativas 2D / Lab RTVE /

Los Goya

INTRODUCTION

The history of the image is as old as mankind itself, using countless techniques, methods, materials and devices, all designed to imitate, with resolute perseverance, the mechanisms of human vision or to expand the experience of reality. That is, from the symbolism of the earliest cave paintings to the invention of linear perspective to the panoramas (from the Greek: global vision) of the 18th and 19th centuries, the history of the image has been determined by these two dimensions; in our digital context, the proximate future of the image presents the possibility of a fusion of these two dimensions, in the direction pointed to by Castañares: “Man will become no more than mind, and this, pure information, able to be digitised and downloaded onto a machine” (p. 61). This future is due precisely to the fact that, according to Debray (1994):

The image does not exist in and of itself: its status and power vary continuously with technical revolutions and changes in collective beliefs. And, nevertheless, the image has always dominated mankind, although the Occidental eye has a history and every era its optical unconscious (p.318).

And so, focussing on the Occidental eye, we can affirm that we move within an optical unconscious, from the techniques of linear perspective, the mechanical technologies of vision (photography, for example) and the panoramas of the 18th and 19th centuries; that is, from devices and technologies that attempt to reproduce our way of “seeing” to devices and technologies that become the experience of “seeing” itself. Thus, we have moved from the construction of “seeing” focussed on the object or the study of the object, to the study of the subject or the subject as the true focus of “seeing”.

Consider the reflections of David Hockney (2002) on linear perspective as a form of representation, as a form of “seeing:

The mirror-lens produces a picture in perspective. The point of view is the mathematical point of view at the centre of the mirror. Perspective is a law of optics. To the extent it was “invented”, this occurred in Florence around 1420-1430. Today, this is the window through which we see the world, in television, films, still photography, etc. The Chinese have no such system. It is said they rejected the notion of a vanishing point in the 11th century because it meant the spectator is not there; in effect, had no movement and so was not alive, although their system was highly sophisticated in the 15th century. The scrolls offer a journey across a landscape. Using a vanishing point would have meant the spectator can no longer move (p. 286).

The panorama, among all of these pre-cinema visual inventions, does appear to include the subject, as an attempt to give the spectator movement, in a first opportunity to select the framing.

The search for this experience of vision, to expand our experience of “seeing” began in 1787 with the panorama of Robert Barker (See Figure 1) similar to the Chinese scrolls which allow the eye to travel.

Figure 1

Panorama of Edimburgo

Note. From Panorama of Edinburgh by Robert Barker, 1787, https://www.aryse.org/la-vision-total-el-panorama-de-barker/

The subject is present in the experience of “seeing”, the subject must move in order for the image itself to have meaning. Peñafiel (2016) affirms that this is the beginning of a “paradigm shift in the construction of the image” (p.166), from object to subject, with the participation of the spectator in the choice of framing, and becoming apparent in 2016 with the first 360º video camera.

Interestingly, the researcher Maria Dolores Bastida de la Calle (2001) offers the following reflection:

Around the 1830’s, the panoramic narrative appeared, showing a painting as an enormous stretch canvas being unrolled from a giant spool and taken up on a second spool. One could say this anticipated in some way modern cinema, and also recalled ancient Chinese scroll painting on silk or paper and gathered up in rolls (p. 207).

Chinese scroll paintings sought the movement of the spectator. Cinema offered pictures in movement but only responded to the concept of “seeing”. The search explored other directions, such as the invention of the panorama. That is, a manner of “seeing” that makes us feel as if we are there, participants in a more ample experience of seeing in which the spectator chooses their own framing, times, moments and instants and the order of images. Bastida de la Calle (2001) goes on to add: The panorama offered the spectator a model that allowed them to direct their gaze from one end to the other, unrestricted by any specific point, just as travellers look out on a passing landscape (2011). Thus, the 360º format is the solution for the exploration of the Western optical unconscious.

The image and “seeing” as an experience, be it immersive or semi-immersive, whatever the intentions of the 360º image, are conditioned by the role of the spectator in the choice of framing.

From the earliest panoramas to all those that followed, they all involved a greater participation of the spectator in “seeing”. From an epistemological point of view, one could argue that all of these devices and technologies had the same intentionality. For a visual illustration of this we need only consider the following advertising pamphlets of a panorama representing London and the Battle of Trafalgar, both by Robert Barker, designed to emphasise their circular vision (see Figures 2 and 3).

Figure2

A view of London and Westminster, 1971

.png)

Note. From Panorama of Edinburgh by Robert Barker, 1787, https://www.aryse.org/la-vision-total-el-panorama-de-barker/

Figure 3

Advertising pamphlet of a panorama representing the Battle of Trafalgar

.jpg)

Note. From Panorama of Edinburgh by Robert Barker, 1787, https://www.aryse.org/la-vision-total-el-panorama-de-barker/

Milestones of 360º narrative in Spain

As indicated in the introduction, when speaking of milestones or changes in paradigm, framing is the fundamental, per se function of the director/producer and the foundation of all audio-visual work. But what happens if this decision is shared between the director/producer and the spectator? Here begins the inflection point, the paradigm shift.

From here, we will deal with the various challenges of 360º narrative being addressed within the Spanish media context. The purpose of this retrospective is to evaluate the degree of innovation of TVE Lab. For this, we will offer a taxonomy or classification, providing a solid overview of the question and so differentiate between 2D content adapted to 360º and 360º content that can also be consumed in 2D (semi-immersive) and content genuinely designed and created in 360º (See Table 1). All of these may be designed from two perspectives: semi-immersive and immersive experiences.

The principal challenge of 360º narrative arises from its very popularity on the internet. For example, Google launched the support for 360º video in 2015; however, the first event offered on this platform was the Coachella Music Festival (2016: ABC Tecnología, 2017), offering live-streamed performances of headline artists and some of the best moments of the festival. In parallel, the possibility to listen in surround sound was implemented, an important factor in the full enjoyment of 360º video using virtual reality headsets. To achieve this, YouTube worked with companies such as VideoStitch and Two Big Ears in the development of technologies compatible with live-stream video and special audio.

In Spain, the media has experimented with this new format in recent years. Benítez de García and Herrera Damas (2018, p. 560) note the pioneering recording of the opera Porgy and Bess VR (El Español, 2015) at the Teatro Real, as well as the retransmission, using the same technology as in 2016, of the San Fermín festival in Pamplona in 360o by the newspaper El País.

From 2016, RTVE LAB broadcast training sessions of a number of athletes participating in the Rio 2016 Olympic Games as well as the program Ministerio del Tiempo (Olivares et al., 2015-2020), making the first recording of an interactive virtual reality episode of a television series.

As illustrated in Table 1, the rate of implementation has been modest but continuous. RTVE LAB has undertaken the majority of projects with the exception of the broadcast in 360º of the Madrid Open (Mutua Madrid Open, 2018), the Copa del Rey in basketball (La Opinión de Málaga, 2020) and the pilot project of La Liga (Real or virtual, 2017) (See Table 2).

Table 1

Evolution of 360º content between 2017 and 2020

|

Product |

Year |

2D/360o |

360o |

Live |

Deferred |

Immersive |

Semi-immersive |

|

Ciudades vacías 360o |

2020 |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Gala de los Premios Goya |

2020 |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Copa del Rey de baloncesto |

2020 |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Gala de los Premios Goya |

2019 |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Madrid Open |

2019 |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Elcano 360o |

2019 |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Teatro Real |

2018 |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Madrid Open |

2018 |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

La Liga |

2017 |

X |

X |

X |

X |

Table 2

Evolution of 360º content between 2015 and 2017

|

Product |

Year |

2D/360o |

360o |

Live |

Deferred |

Immersive |

Semi-immersive |

|

Cyrano 360o |

2017 |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||

|

Cervantes VR |

2017 |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||

|

Ministerio del Tiempo |

2017 |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||

|

Islas Cíes 360o |

2017 |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||

|

Escena 360o |

2017 |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||

|

San Fermín |

2016 |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||

|

Ingeniería romana |

N/D |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||

|

Vive Río - Heroínas |

2016 |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||

|

San Fermín |

2015 |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||

|

Elecciones |

2015 |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

Porgy and Bess |

2015 |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

METHODOLOGY

A dual perspective

The chosen case study was the Goya Awards 2020 ceremony broadcast live in both traditional format and simultaneously in 360º, with a parallel immersive and multicamera signal, in which RTVE LAB returned to an initiative which first began in 2019. The importance of this case lies in the fact that this was one of the first broadcasts of a live event using 360º technology in Spain.

The website of the RTVE LAB provided instructions for viewing the awards in 360º, thus describing the coming experience:

At 22:00, when the awards ceremony begins, a live, immersive broadcast using 4 cameras we allow you to watch the ceremony as if you were sitting in the front row or on the stage at the Palacio de Deportes José María Martín Carpena. (2020a)

The website explained the various ways to enjoy the immersive experience of the event through the website or on YouTube. In both cases, the viewer could move across the image using a touchscreen . It was also possible to download the RTVE VR application, designed to provide an immersive experience by connecting a mobile phone to an adaptor to configure a virtual reality headset. The study was conceived from two perspectives:

Prior interview

Firstly, an interview was conducted with the two directors of RTVE LAB (Esther García Pérez y Marcos Martín) responsible for the design of the 360º broadcast for the awards ceremony . This served to gain insight into the technical aspects and possibilities offered by 360º narrative.

Case study. A live macro event in 360o: the Goya Awards

Secondly, and based on the interview, we designed a research model with the following objectives:

- Establish the conceptual basis of the construction of a 360º “seeing” experience

- To study the different milestones in the development of this format in Spain, both in terms of technologies and content.

- To design an analysis model applicable to the selected fragment of a 360º production.

Given that this is a highly subjective field with a complex ecosystem, we opted for a method of analysis that will reveal objective data. According to Karam (2018), “we live in a community of interpreters and producers of signs, each triggering in turn new interpreters and producers” (p. 11)

Denotative analysis is based on evidence, on what is seen. According to Pérez Báñez (2014, slide 2), denoting is opposed to connotation. It indicates, announces and suggests through formal aspects. In contrast, connotative analysis will seek to find out what causes the image. Thus, shedding light to find out how meaning is produced (Pérez Báñez, 2014, slide 3).

According to Karam (2006, p.7), syntagmatic analysis is a structuralist technique that seeks to establish the surface of the text and the relationship between its parts, or sets of parts, with each other. According to Jessica Samperio (2004), it is useful when applied to audiovisual texts. Karam (2017) agrees, stating “it corresponds to the image of a chain, from which the syntagmatic analysis comes from studying the links” (p.7).

On the other hand, according to Samperio (2004), “paradigmatic relations are the oppositions and contrasts of signifiers that belong to the same system, in the text in which they were used” (p. 64).

From these perspectives, models of connotative/denotative and syntagmatic/paradigmatic analysis are proposed, extrapolating this analysis of the traditional narrative to the 360º narrative to generate taxonomies that are useful when configuring precise messages within the context of the 360º image (See Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3

Application of the denotative/connotative analysis model

|

Type of production |

Denotative |

Connotative |

|

Traditional production |

Length of the take. Optic: Normal, normal or telephoto lens. Angulation: Normal, high-angle or low-angle. Movement: Still shot, slight movement, panoramic, hand cam or moving. Duration: very short, short, standard, long. Composition: Balanced or not. Point of view: Objective or Subjective |

Effects of these parameters and a brief summary of the meaning of the whole. |

|

360º production |

Length of the take, determined by the proxemics of the user. Optic not an issue in the production of meaning. Angulation: Operating the same. Duration: Generally, longer, allowing the user to experience interactivity and freedom of decision. Composition: Multiple compositions in each camera position; planned. Point of view: Always subjective |

Effects of these parameters and a brief summary of the meaning of the whole. The fact of experiencing an event in first person will always modify the meaning. |

Table 4

Application of the syntagmatic/paradigmatic analysis model

|

Types of production |

Syntagmatic |

Paradigmatic |

|

Traditional production |

Type of analysis: Centre to margin. Left to right. Top to bottom. Degree of iconicity: Realistic, medium or abstract. Type of composition: Static, dynamic or spiral. Dimensionality of the image: Proportions of the elements within the frame |

Signifiers found within the visual text. Absences: what remains unsaid. Proof of the commutation of signifiers. Binary opposition. Distinguish between metaphor and anecdote. |

|

Types of production |

Syntagmatic |

Paradigmatic |

|

360º production |

Type of analysis: The type of analysis varies according to where the user is looking. It is recommended to predict the types of analysis which may arise. Degree of iconicity: Operating the same. Type of composition: May be dynamic, static or spiral; a multitude are possible in each camera position and will vary according to the view of the user. Dimensionality of the image: Operating the same |

Signifiers found within the visual text. Absences: what remains unsaid. Proof of the commutation of signifiers. Binary opposition. Distinguish between metaphor and anecdote. |

It was decided to analyse the fragment in which Benedicta Sánchez received the Goya for Best New Actress for her role in O que arde (Laxe, 2019), as this was one of the most viewed segments of the ceremony according to RTVE metrics and whose analysis can be extrapolated to any other moment of the event.

The aim is to determine the shared parameters of both narratives which could be useful for the generation of meaning in this new visual ecosystem. That is, the canvas on which we have worked so far is blurred within this new ecosystem, while the syntax through which we structure signifiers is different. What possibilities does it offer us and what limitations do we face?

By applying the analysis models of traditional narratives adapted for application to 360º narratives, we can reflect on the needs of 360º video. The adaptations of both analysis models are provided below.

Adaptation of denotative and connotative analysis to 360º video

We cannot analyse the size of the frame but rather are obliged to analyse the length of the take chosen by the user, determined by the proxemics of the spectator/user, acquired according to the position of the camera. We analysed the following parameters:

- Length of the take determined by the proxemics of the spectator.

- Optics are not used narratively or compositionally.

- Movement is redefined, and the spectator/user choses the framing, generating a personalised framing of the environment. Even with camara movement, the spectator is free to frame this movement as they wish.

- The concept of duration is totally redefined by giving freedom to the user to recognise the environment. The ‘visits’ to each camera are much longer.

- Angulation functions the same.

Apart from the first-person experience and empathy as intrinsic signifiers, the meanings employed, and their relations continue to be the same in a 360º video environment. Analyses can be made to predict the framing created by the spectator in order to guide their attention in benefit of the narrative. This is also the case with the dimensionality of the elements. These depend on the position of the camera creating distinct proxemic relations in 360º panorama, generating different meanings. These meanings are predictable if the camera positions are studied adequately

360o video framing show very different dimensionalities from the same camera position, and are, a priori, the decision of the user. Therefore, the architect, no longer the scriptwriter of the narrative, must guide the interactive freedom of the user in order to avoid the paradox of interactivity identified by Jorge Esteban Blein (Narrativa VR, 2018), and still produce the intended meaning or meanings. The dimensionalities of each sector within the 360º environment can be predicted .

Adaptation of syntagmatic and paradigmatic analysis to 360º video

The principal meanings detected in each unit of 360º video are used and quantified just as in traditional video production, and tests of the commutation of signifiers or binary oppositions to evaluate the signifier power, are equally functional and revealing in the analysis of 360º video. Thus, these can be perfectly used to create specific meanings within constructed narratives or to guide the attention of the user.

RESULTS OF THE PROPOSED ANALYSIS MODEL AT THE MOST VIEWED MOMENT OF THE 360º GOYA AWARDS: BENEDICTA RECEIVES THE AWARD FROM BEST

NEW ACTRESS

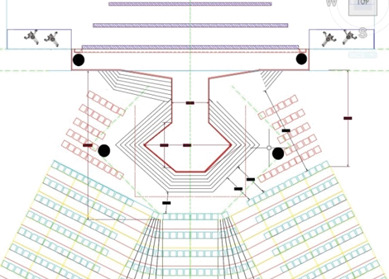

We begin with the production design which will offer insight into the results. First, the positions of the four 360º cameras (See Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4

Production design

Note. Image from the organisers of the 360º production of the Goya Awards 2020.

Figure 5

Position of a 360º camera

Note. Image from the organisers of the 360º production of the Goya Awards 2020.

Taking the stage as north, the figures 6a, 6b, 6c and 6d show the 4 views of the 360º cameras.

Figure 6

The four views of the 360º cameras at the Goya Awards

(a) (b)

(c) (d)

Note. (a) General view from the left. (b) General view from the right. (c) Closeup from the left. (d) Closeup from the right. Benedicta Sánchez, Best New Actress / Goya Awards 2020, by RTVE, January 25, 2020, YouTube (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zEjwyyiIb6s).

The RTVE LAB created a plan for the location of the VR 360º cameras, but these could not interfere with needs of traditional production and so were located where possible. Thus, the 360º VR production did not achieve the full semiotic isomorphism originally hoped for: to experience the Goya Awards from a privileged position.

These locations were chosen in order to maintain the original intent to transmit the experience of the ceremony in the first person. The result was the generation of two distinct ecosystems operating in parallel; which raises the question: Can they coexist? While this is territory yet to be explored, jumping from traditional viewing to experiencing a specific moment in the first person can be highly enriching in staging the message.

Analysis of the traditional vs 360º production

Analysing the fragment in which Benedicta Sánchez received the Goya for Best New Actress using the adapted analysis model, the results were as follows.

In the formal denotative aspects of the traditional production, Luis Campoy, the producer of the awards ceremony, narrates this fragment of the Awards ceremony composing takes according to a conventional visual syntax, and from a principally objective point of view. Shots of standard duration predominate with a number of long takes and also some exceptionally long takes of over 20 seconds, following the action with sequential takes. Each narrative unit has a reading from left to right, top to bottom, centre to margin, producing a characteristic relation between the semiotic nucleus and the signifiers which determine the final meaning of the whole.

In terms of the scale of the camera takes, there are general long shots to illustrate the scenario and position the viewer as well as close-ups to capture details and show the emotion of the participants. As in the moment when Benedicta mentions the director of the film “O que arde” (Laxe, 2019), Campoy immediately offers the viewers a close-up of the director smiling happily. Thus, the camera shows itself to be ubiquitous, in keeping with conventional film production techniques. An analysis of the optics shows no use of narrative.

In terms of connotative analysis, there are two clear semiotic nuclei, the stage with the screen and Benedicta.

If we observe the results of the syntagmatic analysis, we see that descriptive shots typically read from left to right. Long shots have a spiral composition, offering depth and the possibility of playing with the order of reading. In terms of the degree of iconicity, the entire fragment fits within a frame of realist figuration, with the dimensionality varying according to the type of shot.

For a paradigmatic analysis, each signifier of the narrative is subjected to a commutation test, imagining the narrative unit with a changed meaning or a series of similar tests which validate the signifiers.

The narrative units of the same sequence shot in 360º video differ from the traditional. We understand narrative units as the cut in the shot from a specific camera, and within these units, we aim to divide the 360º into possible shots that can be configured by the spectator making use of the interactivity provided. Barthes (1971) points to the importance with the semiotic undertaking to divide the text or body of analysis into minimal units of meaning in order to classify them according to the syntagmatic relations between them.

In 360º video, the framing is not defined by the director, now transformed into the architect of an interactive experience where multiple framings are made possible by the position of the camera. The optic is no longer relevant to narrative. The angulation is. From the camera located in front of the stage where Benedicta is standing, we have a low-angle shot in first person. Two types of movement can be distinguished: that of the camera, which here does not occur, and that taking place within the 360º sphere at the will of the spectator. Here the architect of the experience should seek to compose possible frames and guide the attention of the viewer.

Finally, on a connotative level, the general meanings are the same than in traditional production but with a difference: we not only observe, we live the experience. Furthermore, the paradigmatic analysis reveals the same as an analysis of the conventional production.

DISCUSSION

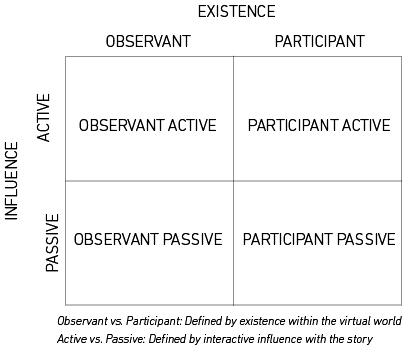

Analysis shows that, despite sharing certain formal aspects (some modified and conditioned by the use of proxemics and interactivity) it appears there are narratives meant to be viewed and other narratives to be experienced. According to Dolan and Parets (2016) there are various forms of existence within the 360º world, but not all appear to be compatible with 360º video and the degree of interactivity required takes precedence over all others, that is, the first person experience which makes use of the intrinsic freedom to experience, changing the manner of connotation. Similarly, and despite the fact that signifiers revealed in the filmic space are the same, especially at the paradigmatic level, the first person experience changes not the meaning but rather the use of the of signifiers and the manner they are experienced. There are also different narratives. Not all stories are suited for telling in the first person, although it may be effective to jump from the third to first person eventually. One interesting method is that proposed by Jorge Esteban Blein (Narrativa VR, 2017), the narrative from a mixed perspective: to see a person at an awards ceremony and then have the option to live their experience from their point of view.

Dolan and Parets (2016) speak of various modes of existence within the world of 360º but not all seem to be compatible with 360º video, nor with the degree of interactivity required by this medium (See Figure 7).

Figure 7

Existence/influence relation

Note. From Redefining the axiom of story: The VR and 360 video complex, by Dolan and Parets, January 14 2016, TechCrush (https://techcrunch.com/2016/01/14/redefining-the-axiom-of-story-the-vr-and-360-video-complex/).

For example, if we combine both narratives it would be interesting to substitute the traditional narrative for a 360º experience specifically during Benedicta’s speech to emphasises the first-person experience of this moment. .

The characteristics of 360º narration make it the most appropriate for first person story telling. However, co-existence is possible by perfecting and harnessing these new tools for the production of meaning.

Jorge Esteban Blein speaks of tools to monitor places most observed by users within the 360º space (Barreira A+D, 2020). Heat maps1 offered by YouTube provide colour coded maps of the most viewed locations in the 360º environment. The results are often surprising and very useful in generating strategies to guide the attention of users within the 360º narrative. Unfortunately, Youtube no longer offers this service.

Spectators are learning to interpret this language while also learning to use the necessary technology, representing a challenge to the human senses. Most probable scenario will be the standardisation of the production of scripts for 360º narratives and the necessary technologies. The stigmas associated with a change in paradigm have yet to be overcome, both from a conceptual point of view and in terms of user accessibility and usability. The broadcast of the Goya Awards 2020 may be regarded as a premature combining of both ecosystems but can also be considered as a valuable case study from which to draw conclusions. The 360º video in the Goya 2020 event was viewed by many professionals in traditional media as more of an obstacle than an opportunity to create and enrich the production of meaning. The planning and semiotics of complete 360º spaces supposes a logistical conundrum for pre-production. The 360º cameras are visible and obstruct the composition of shots in the traditional ecosystem. Although a bi-directional adaptation of both narratives would have been ideal this was not the case, resulting in the loss of the specificity of 360º narrative. Thus, if it had been designed as a mixed narrative from the outset, 360º video could have enhanced the semiosis of the event.

As has been the case since the birth of moving images, the utility of the semiotics of new tools has been dependent on a change in narrative paradigms and mentality of those within the pre-existing ecosystem, given the choral nature of audio-visual production. Only with these changes can new tools achieve their full potential.

CONCLUSIONS

Research into the conceptual foundations of 360º vision leads us to understand that in these circumstances the true protagonist is the subject. Additionally, vision is an experience that is also defined by its interactivity, which points the limitations of the role of director in framing the visual experience and thus “unframing” the spectator and putting the power of decision into their hands.

This synthesis, beginning from the earliest versions of 360º narratives in the form of panoramas, lays the foundations for the challenges and opportunities offered by the necessary redefinition of the concept of “seeing” itself. This, fundamentally, is the crossroads faced by all those involved in the new definition of 360º narrative; that is, a new paradigm without the prior choice of framing in a radical change in the concept of vision. This may lead researchers and professionals to reject the figure of the subject in 360º narratives; the centre of vision, now with the ability to select a frame, interacting and thus redefining the experience of “seeing” itself.

This situation has led us to propose analysing the course of 360º narrative as manifested in a macro event of the Goya Awards 2020: the contributions, limitations, risks assumed and what remains to be done; in addition to the challenge of combining both narrative techniques, the traditional and 360º. This study has been greatly facilitated by the development of new tools of analysis.

The application of the analysis model has allowed us to draw conclusions from the experience of the Goya Awards. For us, this experience has served as a laboratory, enabling a comparison, confrontation and a dialectic of both narratives and, as is well known, the dialectic is one of the most fruitful tools in generating new knowledge

Thus, we can conclude the following:

- Achieving the coexistence of both semiotic ecosystems in a single production, as with the Goya 2020, is difficult but not impossible. The findings of the study show that both systems share a number of parameters in the creation of meaning

- Traditional narrative is still able to reach places where 360º narrative cannot and remains more flexible at the moment. This is also the case with certain important formal denotative aspects such as the use of optics for narrative purposes. And where traditional narrative does not reach, the true first-person experience of the narrative, 360º offers the solution.

- Maturity is needed in the processes of visual semiosis of 360º video. It is not only about the viewer living a virtual experience parallel to reality, but about generating precise messages and complex narratives assuming that the basis of the visual syntax of the last century and a quarter, the framing, has been surpassed. Without adequate reflection, this may become merely another gadget relegated to fairground attractions, despite its immeasurable potential.

- A standardisation of technology is necessary for the satisfactory first-person experience and the climatization of the spectator/user who experiences virtual movement visually but not with the inner ear. Becoming accustomed to 360º narrative is popularly known as “growing VR legs”, which according to Jorge Esteban Blein is when the user becomes accustomed to using their VR headset.

- We must analyse and predict possible movements of the spectator in exercising their freedom to create a system of freedom-coercion for narrative purposes.

- We agree with Karam (2006) in terms of the following:

“The issue of convention, or codified and regulated rules, raises a major problem between freedom and coercion. How does freedom emerge from the coercion imposed by language?; or conversely, why, given all the possibilities of representation (including artistic creation, poetry, etc.) are we forced to resort to expressive systems that have degrees of determination and codification? Codes are operators that allow degrees of freedom and, at times, the code itself indicates how to operate with freedom” (Karam, 2006. p.4).

- It is necessary to find solutions for the broadcast of non-film events, such as the Goya Awards, in the positioning of 360º cameras to create the specific desired narrative. For the Goya Awards 2020, the 360º camera positions were the subject of difficult negotiations to find positions that did not hinder traditional production. The chosen locations were those which best served the intended mis-en-scene within the limitations imposed by the needs of traditional production. Ways must be found for different technologies to co-exist, not only on the narrative level but also in terms of logistics, staging and scenography.

- We believe that taking these observations into consideration, it is possible to achieve a semiotic symbiosis. A condition is the absence of any logistical hindrances or friction given the compatibility of the two systems.

- We draw from a pre-existing narrative language, but we must consider the possibility it will take on its own reality and eventually split into two.

Finally, with the aim of assisting future research into this field, it should be noted that this work consists of a case study, based on the first-hand experience of producers from RTVE LAB of the Goya Awards 2020 ceremony in 360º. The paper offers a comparative analysis of 360º and traditional production to determine the precision of the audiovisual message transmitted to the viewer, given the interest stirred by two parallel productions. 360º video is a rich and broad field in terms of narrative possibilities and creation of new visual syntax. Figures such as Jorge Esteban Blein are developing new terminology, specific narrative variants or scripts in which 360º video offers great potential. However, there is still much to be decided about whether these are parallel processes of semiosis processes or if they could and should coexist within mixed narratives.

This study is limited to the use of 360º video for audio-visual narrative, with the first-person experience of an event as an invisible protagonist and with a very limited level of interactivity, based on deciding nothing other than where to direct your gaze, generating, consciously or unconsciously, an à la carte framing of the event.

There are other audiovisual products offering greater interactivity, closer to gamification than to the role of spectator. However, here the aim was to study the role of a new visual syntax in the narrative field. To date, framing has been and remains a key element in audiovisual narrative, defining the visual composition of a scene by the cinematographer and film director. Through this composition essential information is transmitted. Now, framing plays an even more important role but without the limitations of the traditional camera’s framed view. Here the framing is dynamic, creating a tension between interactivity and narrative guidance. This is an exciting field of study in which there is still much to explore.

REFERENCES

ABC Tecnología (2017, september 25th). YouTube lanza las retransmisiones en 360 grados en directo y sonido espacial. https://www.abc.es/tecnologia/redes/abci-youtube-lanza-retransmisiones-360-grados-directo-y-sonido-espacial-201604182151_noticia.html

Aristóteles. (2000). Poética. Icaria editorial. (Obra original publicada ca. 335 A.E.C.)

Arrieta, E. (2016, julio). Wolder lanza la primera cámara 360o de una marca española. Expansión Tecnología. https://www.expansion.com/tecnologia/2016/07/21/5790c40146163f47548b458c.html

Barreira A+D. (2020, 25 de marzo). Desafíos de la narrativa en VR: Lo que el cine ya superó, con Jorge Esteban Blein [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FDAKIsIh53o

Barthes, R. (1971). Elementos de semiología. Alberto Corazón Editor.

Bastida de la Calle, M. (2001). El Panorama: una manifestación artística marginal del siglo xix. Espacio, Tiempo y Forma. Serie VII, (14). https://doi.org/10.5944/etfvii.14.2001.2378

Benítez de García, M. J., & Herrera Damas, S. (2018). Los primeros pasos del reportaje inmersivo a través de vídeos en 360o. Historia y Comunicación Social, 23(2), 547-566.

Castañares, W. (2011). Realidad virtual, mímesis y simulación. Cuadernos de Información y Comunicación, 16, 59-81.

Debray, R. (1994). Vida y Muerte de la imagen. Paidós.

Dolan, D., & Parets, M. (2016, January 14th). Redefining the axiom of story: The VR and 360 video complex. TechCrunch. https://techcrunch.com/2016/01/14/redefining-the-axiom-of-story-the-vr-and-360-video-complex/

El español. (2015, september 10th). Porgy and Bess VR / Ópera 360 [Video]. YouTube.

Gubern, R. (2014). Historia del cine. Anagrama.

Haneger, M. (2014). La cinefilia en la época de la poscinematografía. L´atalante, (18), 7-16. https://revistaatalante.com/index.php/atalante/issue/view/13

Hockney, D. (2002). El conocimiento secreto. Destino.

Jump Into Reality. (2019, October 29th) ¿Que es la realidad virtual en tiempo real? [Video]. YouTube.

Karam, T. (2006, December 1st). Introducción a la semiótica de la imagen. Portal comunicación.com.

Karam, T. (2018, January 29th). Sesión 0 [Simposio]. Seminario Semiótica, Cultura y Tecnologías en Comunicación: Industrias, Discursos, Materialidades y Públicos, Universidad Autónoma de la Ciudad de México, México D. F.

La opinión de Málaga. (2020, February 14th). La Copa del Rey, en 360 grados gracias a Telefónica. https://www.laopiniondemalaga.es/unicaja/2020/02/14/copa-rey-360-grados-gracias-27639216.html

Laxe, O. (Director). (2019). O que arde [Película]. Miramemira; Kowalski Films; 4 a 4 Productions; Tarántula Luxembourg.

Mohan, N. (2016, 18 de abril). Un paso más cerca de la realidad: presentamos las retransmisiones en directo en 360o y el audio espacial en YouTube. Google Blog Oficial de España. https://espana.googleblog.com/2016/04/un-paso-mas-cerca-de-la-realidad.html

Mutua Madrid Open. (2018, May 13th). Daily. El Mutua Madrid Open, pionero en la emisión 360o.[Video].YouTube.

Narrativa VR. (2017, June 14th). ¿Qué es la narrativa desde un punto de vista mixto en realidad virtual? [Video]. YouTube.

Narrativa VR. (2018, February 22th). Keynote de Jorge Esteban Blein en The XR Date [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vfEZOT4wH7I

Olivares, J., Yubero, A., Roy, M, & Vigil, M. (Productores ejecutivos). (2015-2020). El Ministerio del tiempo [Serie de Televisión]. Cliffhanger; Globomedia; TVE.

Peñafiel, C. (2016). Reinvención del periodismo en el ecosistema digital y narrativas AdComunica, (12), 163–182.

Pérez Báñez, M. (2014, November 28th). Taller de imagen. Denotación y connotación [Diapositiva de PowerPoint]. SlideShare.

Real o virtual. (2017, July 7th). La primera transmisión 360 en directo de la Champions League, en el OVR17.

RTVE. (2016, July 20th). Vive Río 2016 / Heroínas / Vídeo ٣٦٠º VR / LAB RTVE.es [Video]. YouTube.

RTVE. (2020a, January 25th). ¿Cómo seguir los Goya en RTVE.es? https://www.rtve.es/noticias/20200125/como-seguir-goya-360-rtvees/1995944.shtml

RTVE. (2020b, January 25th). Benedicta Sánchez, mejor actriz revelación / Premios Goya 2020 [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zEjwyyiIb6s

Samperio, J. (2004). Análisis de la representación de la mujer en los medios impresos de la campaña de El palacio de Hierro [Tesis de licenciatura, Universidad de las Américas Puebla]. Colección de Tesis Doctorales.

1 Here are two heatmap examples (although YouTube heatmaps are no longer available as a tool): <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZhUPuB2iaoM>, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XBGi_

QUQ6VA>