THE BEAUX-ARTS POCHÉ AND MODERN

ARCHITECTURE IN LATIN AMERICA

EL POCHÉ DE LA TRADICIÓN BEAUX-ARTS

Y LA ARQUITECTURA MODERNA EN AMÉRICA LATINA

Claudia Costa Cabral

Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0079-1861

Received: December 23, 2024

Accepted: May 20, 2025

doi: https://doi.org/10.26439/limaq2025.n016.7661

Like many terms within the Beaux-Arts vocabulary, poché had a clear and straightforward definition: the drawing convention of darkening the masonry sectioned in a plan. However, it also comprised more opaque meanings. Modern architecture in Latin America was introduced by architects trained within this academic tradition. This paper aims to show that the poché was widely employed by these architects in various contexts—ranging from its use as a technique to integrate modern buildings into the urban fabric while preserving large interior spaces as regular figures, to its role in organizing functional components and enabling transparency. Alongside composition and character, the Beaux-Arts poché—with its multiple and perhaps slippery meanings—does not seem to have been entirely abandoned by architectural practices that embraced the free plan, free façade, pilotis, roof garden, and horizontal window: elements usually regarded as the hallmarks of modernity.

academic tradition, Beaux-Arts, Latin America, modern architecture, poché

Como muchos términos del vocabulario de la École des Beaux-Arts, poché tenía una definición clara y directa: la convención gráfica de oscurecer la mampostería representada en corte en un plano. Sin embargo, también aludía a significados más complejos. Partiendo del hecho de que la arquitectura moderna en América Latina fue introducida por profesionales formados en esta tradición académica, este artículo propone mostrar que el poché fue ampliamente empleado por ellos en distintos contextos: desde su uso como recurso para integrar los edificios modernos en el tejido urbano, al tiempo que se preservaban grandes espacios interiores concebidos como figuras regulares, hasta su función en la organización de los componentes funcionales y en la generación de transparencias. Junto con la composición y el carácter, el poché beauxartiano —con sus múltiples y, quizá, resbaladizos sentidos— no parece haber sido del todo abandonado por aquellas prácticas arquitectónicas que hicieron suyos la planta libre, la fachada libre, los pilotis, la terraza-jardín y la ventana horizontal, elementos habitualmente considerados como emblemas de la modernidad.

tradición académica, Beaux Arts, América Latina, arquitectura moderna, poché

This is an open access article, published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license.

Introduction1

Arthur Drexler’s preface to the catalog of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) exhibition The Architecture of the École des Beaux-Arts, which opened in 1975, highlighted the connection between the triumph of modern architecture and the pedagogy of the German Bauhaus. Drexler argued that although Bauhaus disappeared as an institution, it flourished as a doctrine. Aspiring to a global role, this doctrine required a void to fill and the only available universal educational system was the one developed and disseminated by the École des Beaux-Arts. This system, however, came to be described as one aimed at solving what were no longer “real problems,” as Drexler put it. “And since history is written by the victors,” he added, it “has helped to perpetuate confusion as to what was lost” (Drexler, 1975, p. 3).

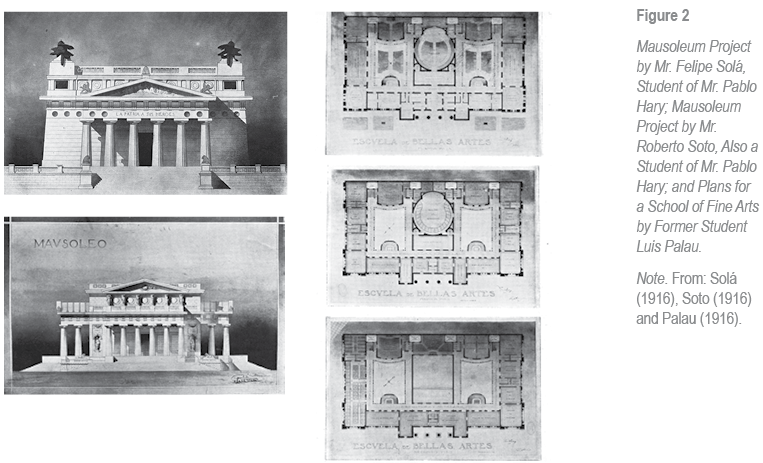

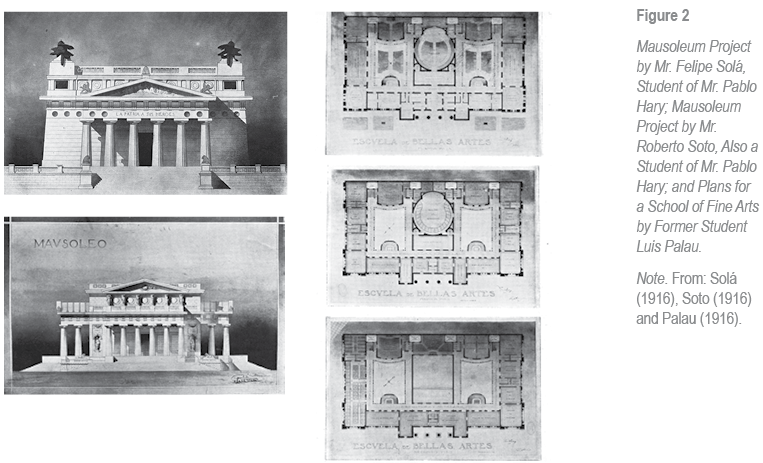

Like many terms within the Beaux-Arts vocabulary, poché had a clear and straightforward definition: the drawing convention of darkening the masonry sectioned in a plan. However, it also comprised more opaque meanings. “Composition” was another keyword of the Beaux-Arts system. The exhibition catalog defined it as the bringing together of several parts into a unified whole, integrating exterior volumes with corresponding interior spaces and involving “the conception of the building as a three-dimensional entity through which one mentally ‘walked’ as one designed” (Drexler, 1975, p. 9). The poché was essential to this idea of composition: it accommodated interior and exterior divergences, geometrically constructing figural spaces along the building’s spatial path and secured areas for both structural support and services (Figures 1 and 2).

Modern architecture in Latin America was introduced by architects trained within this academic tradition. This paper aims to show that the poché was widely employed by these architects in various contexts—ranging from its use as a technique to integrate modern buildings into the urban fabric while preserving large interior spaces as regular figures, to its role in organizing functional components and allow transparency.

Contrary to the Bauhaus’ doctrinaire perception, it indeed addressed “real problems,” which involved the adaptation of modern architecture to traditional city patterns and the management of complementary service systems within buildings.

The Beaux-Arts Poché

Authors who have recently focused on the architectural poché as a topic, including its historical and contemporary uses, largely agree that defining the term remains “elusive and elliptical” (Young, 2019, p. 191; Lueder, 2015). They also emphasized the antinomy between the poché and the preferred structural system of modern architecture, which is typically identified with the independent skeleton. Michael Young noticed that Le Corbusier’s “Five Points of New Architecture” could be, in part, “an attack on poché as descended from academic and vernacular tradition” (Young, 2019, p. 194). Christoph Lueder described the Beaux-Arts poché as a tectonic and drawing convention based on a presumed congruency between space and structure, “in opposition to the free plan theorized by Le Corbusier in 1926” (Lueder, 2015, p. 125).

The ambiguities surrounding the term poché within the Beaux-Arts vocabulary are probably not alien to the very way in which the academic training was organized. Officially, the École des Beaux-Arts was established in Paris in 1819 and taught architecture until 1968. Yet, the genesis of the Beaux-Arts theoretical and practical foundations must be traced back to the Académie Royale d’Architecture, founded by Colbert in Paris. As Richard Chafee has thoroughly explained, the École was not newly established in 1819 but had been transformed since 1793 from the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture and the Académie Royale d’Architecture (Chafee, 1977, p. 61). The role assigned to the Académie involved both improvement and control. It sought to foster architectural knowledge, address theoretical problems, and refine the academic doctrine and its rules—understood as universal principles founded in the authority of Classicism (Hautecoeur, 1964, p. 24). The scope of activities promoted by the École comprised lectures and courses, yet, as Chafee observed, what was taught there “was material communicable in words.” The students’ drawing boards were located in the ateliers, not within the Académie’s École. Even after the French Revolution and the eventual settlement of the École in its definitive home on Quai Malaquais—in buildings adapted by Félix Duban—the students did not learn to design there but outside the school, in an atelier supervised by an architect (patron) (Chafee, 1977, pp. 62, 75).

The use of the term poché to refer to the drawing convention of darkening the masonry sectioned in a plan probably belonged mainly to the spoken jargon of the ateliers rather than to the academic literature. The poché was part of the graphic code shared by architects and builders—a representational system that allowed the postponement of more practical decisions related to construction and services in favor of an immediate focus on more strictly artistic and architectural issues, such as the figural and distributive aspects of composition (Corona Martínez, 1990, p. 170).

The term “composition” migrated from painting to architecture toward the end of the eighteenth century (Gregotti, 1986; Rowe, 1976). Werner Szambien defined composition, in a general sense, as “a mental operation leading to the conception of a whole which assembles several differentiated elements” (Szambien, 1986, p. 64). He noticed the potentially contradictory fact that “the very idea of heterogeneousness and confusion contained in that word was opposed to architecture’s asserted aim: to reach unity, harmony and symmetry” (Szambien, 1986, p. 64). Strictly speaking, in the academic composition, the “differentiated elements” corresponded to a stable repertory of architectural elements—most of them consistent with the classical language and therefore already shaped and categorized—which should be assembled according to an accepted set of rules: the “principles of composition,” mostly learned from the study of past examples.

“In the teaching of all the patrons,” observed Chafee, “two constants are evident: the importance of the plan, and the importance of a vague quality often called ‘character’” (Chafee, 1977, p. 97). The typical Beaux-Arts plan was governed by the principles of axial composition, manipulating multiple sequences of geometrically defined, symmetrically arranged spaces along the major and minor axes. The axial composition implied a particular idea of movement—a unifying experience of the building’s interior space obtained through a series of discrete and even contrasting adjacent rooms.

As Corona Martínez has noticed, “spaces exist by their limits” (Corona Martínez, 1990, p. 179). The poché, understood as the solid, darkened zones of masonry in a plan, was crucial to shaping the void, giving spatial definition to the room as a geometrical figure. In this sense, the poché was instrumental in both preserving the formal autonomy of each singular room and controlling the relationship to one another, accommodating the inevitable geometrical discrepancies among them.

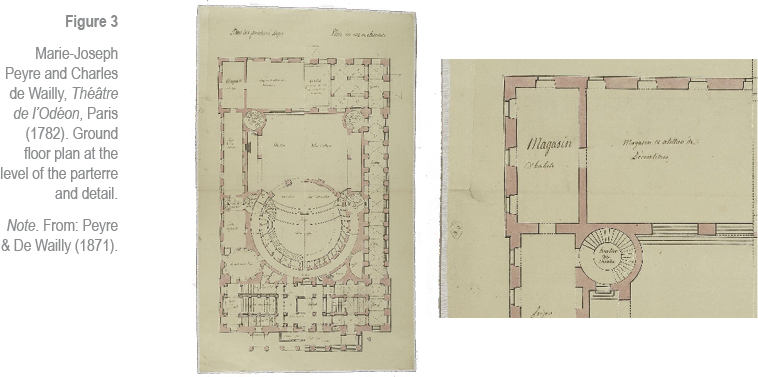

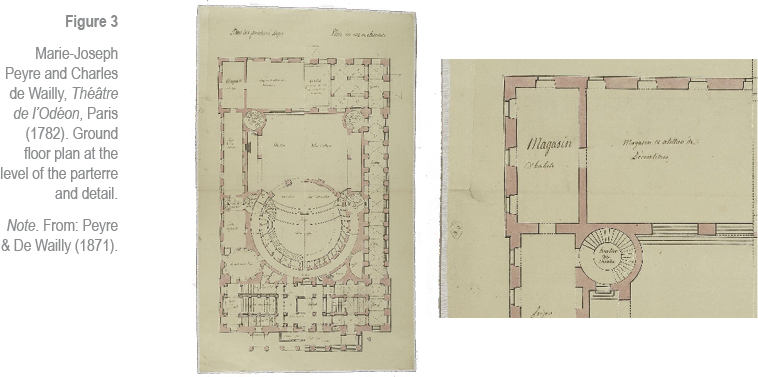

The term poché was also associated with poche—meaning ‘little pocket’ or ‘cavity’—suggesting that these darkened zones could not be entirely solid. A secondary meaning referred to the practice of inserting tiny service spaces—such as utility compartments, auxiliary passages, and service stairs—within the solid sections of masonry, allowing them to remain functional while remaining out of sight (Figure 3).

The poché was also related to character. In the catalog of the MoMA’s 1975 exhibition, Drexler remembered that “the majority of architects who reached professional maturity in the 1940s had received at least an American version of Beaux-Arts training” (Drexler, 1975, p. 4). The manual written by John Harbeson in 1926, The Study of Architectural Design, with Special Reference to the Program of the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design, summarized much of the École’s pedagogy as it had been transmitted to America (Lueder, 2015, p. 127). Harbeson noted that the poché would “at once give scale and character to a plan” (Harbeson, 1926, p. 101). The poché revealed the hierarchy among rooms: larger and more important spaces in a plan were given thicker walls, big enough not only to provide structural support but also to admit a “richer outline,” as the poché could incorporate “pilasters, engaged columns, panels, or niches, which would be lacking in corridors or rooms intended for the minor services of the building” (Harbeson, 1926, p. 137).

According to Alan Colquhoun, by the nineteenth century, the principles of design developed and transmitted through the academic tradition were common to all styles: “composition, in academic usage, seems to presuppose a body of rules that are a-stylar” (Colquhoun, 1986, p. 15).2 As he argued, “this idea of composition was directly inherited by the 20th century avant-garde from the academic tradition” (p. 15).

Alongside composition and character, the Beaux-Arts poché—with its multiple and perhaps slippery meanings—does not appear to have been entirely abandoned by architectural practices that embraced the free plan, free façade, pilotis, roof garden, and horizontal window: elements usually regarded as the hallmarks of modernity.

The Critical Recovery of the Poché

The historiographical reassessment of the Beaux-Arts system in the late 1970s and 1980s was part of a general effort in which the MoMA’s exhibition The Architecture of the École des Beaux-Arts (1975) undoubtedly played a key role. As discussed previously, authors like Drexler (1975), Colquhoun (1986), Szambien (1986), and Corona Martínez (1990) offered compelling reflections on the academic concepts of composition and character. Nevertheless, the historiographical recovery of the poché as a concept might have had earlier and American roots.

According to Colin Rowe, the term poché had been forgotten, or “relegated to a catalog of obsolete categories,” until Robert Venturi revived its usefulness in 1966. Rowe used the idea of poché in his argument in favor of an articulated urban texture. Appealing to what he himself acknowledged as an “overhauled sense” of the term, he valued its ability to engage and be engaged, to act as both figure and ground, suggesting that a building itself could become a type of poché (Rowe & Koetter, 1979, pp. 78–79).

Venturi’s critical and historiographical recovery of the poché, exposed in “The Inside and the Outside,” becomes a cornerstone in his argument concerning contradiction in architecture. He claims that the so-called flowing space, produced by an architecture of interrelated horizontal and vertical planes connected by areas of plate glass—as in Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion—has been considered the boldest contribution of modern architecture. “Such cornerless architecture,” he says, “implied an ultimate continuity of space” and the “oneness of interior and exterior space” (Venturi, 1977, p. 70). Nevertheless, Venturi argues that “the old tradition of enclosed and contrasted inside space (…) has been recognized by some modern masters,” even though it has not been emphasized by historians (Venturi, 1977, p. 70).

The poché is part of that tradition. Its persistence is exemplified by the work of Louis Kahn, whose “servant space,” sometimes used to harbor mechanical equipment, is compared to “the poché in the walls of Roman and Baroque architecture,” both regarded as “alternative means of accommodating an inside different from the outside” (Venturi, 1977, p. 82). Moreover, Venturi asserts that “contradiction, or at least contrast, between the inside and the outside is an essential characteristic of urban architecture,” and that the poché was a way to cope with “the space left over by this contradiction” (Venturi, 1977, p. 84).

Venturi and Rowe’s critical framework for understanding the academic poché as a design resource with multiple uses may help clarify the argument at stake here. If the poché was a compositional technique employed to accommodate geometrical discrepancies between adjacent interior spaces—as required by the Beaux-Arts plan—it was also used to inscribe regular voids inside irregular exterior volumes. Besides, if the poché could manage discontinuities, as in the interior/exterior contrast discussed by Venturi, it also proved to be a helpful device considering the structural and mechanical demands of buildings. Although aligned with modern architecture and its new sense of space continuity, architects in Latin America do not seem to have completely discarded the old poché technique. On the contrary, they used it to serve the aims of modern space, at least in two different situations, which may or may not coexist within a single building: first, the insertion of the modern building into the traditional urban block; and second, the management of functional components and service systems to allow the maximum transparency.

The Poché and the City

The use of the poché in the urban sense, as suggested by Rowe and Venturi, can be observed in the work of several modern architects in Latin America. However, one would probably not find any recorded written mention of the term by the authors of these buildings. Venturi notes that residual spaces are “sometimes awkward,” quoting Kahn’s assertion that “a building should have bad spaces as well as good spaces” (Venturi, 1977, p. 82). One might say that urban parcels are also frequently “awkward,” being the result of long-term processes of subdivision and/or reintegration, frequently shaped by private and circumstantial interests rather than by coherent public planning policies.

The poché might be understood as a sort of “realpolitik” for modern architecture. As explained by José Luis Romero in the classic Latinomérica: las ciudades y las ideas, the crisis of 1930 unified the destinies of Latin American capital cities. The rural exodus, or the “offensive of the countryside on the city,” manifested itself in the demographic and urban explosion that changed the physiognomy of cities across the continent (Romero, 2007, p. 321). The development of modern architecture in the region coincided with these social and economic processes and certainly played a role in the construction of this new urban physiognomy.

The traditional urban block, though often subdivided into awkward lots, retained both internal and external constructive logic, mainly directed toward maximizing building capacity and lot coverage. The densification and verticalization of the traditional city block frequently relied on what Carlo Aymonino called “distorted typologies”— typologies shaped a posteriori to reach the limits of the solely pre-established non- aedificandi areas: the streets (Aymonino, 1984, p. 76).

The theater was among these distorted typologies. From Rino Levi’s Cine Ufa-Palácio (São Paulo) in the 1930s to Mario Roberto Álvarez and Macedonio Oscar Ruiz’s Teatro Municipal General San Martín (Buenos Aires) in the 1950s, a series of similar urban facilities were designed accepting the external pressure imposed by irregularly shaped lots (Figure 4).

Rino Levi designed the Cine Ipiranga in 1941 and the Teatro Cultura Artística in 1942–1943 (Figure 4). The Cine Ipiranga occupied the ground floor of the high-rise building that housed the Hotel Excelsior, extending across the entire surface of a trapezoidal lot. Levi stretched a regular portico along the street, aligned with the hotel’s façade. The entrance to the hotel was squeezed at one side of the portico, occupying the narrower, straighter section of the lot perpendicular to the street. The larger, deeper portion of the lot—where the big movie hall could be accommodated—was angled in relation to the street. Beyond the shared portico, the entrance, foyer, and waiting room were conceived as a sequence of regular spaces assembled along a central axis, parallel to the lot’s angled limit. The ticket offices, symmetrically placed on either side of this axis, function as a poché, absorbing the spatial irregularities generated by this shift. On the second floor, taking advantage of the difference between the tapered figure of the acoustically shaped movie hall and the trapezoidal shape of the lot, Levi used the residual areas as a poché, housing staircases that led to the galleries on both sides of the room.3

The Teatro Cultura Artística’s bilateral symmetrical plan occupied a parcel that, except from the front alignment, had a broken outline. Using the poché technique, minor service spaces were transferred to the peripheral rear and side zones, allowing the architect to build major, regular spaces inside an irregular site.

Mario Roberto Álvarez and Macedonio Oscar Ruiz adopted a similar strategy in the Teatro Municipal General San Martín (1953–1960), a vast complex situated on a deep lot between party walls (Figure 5). The bold, unobstructed, and regular 260 m2 foyer and exhibition hall—one of the building’s most distinctive features—was made possible through the old poché idea. Service spaces, lifts, and secondary stairs were organized in two rows along both sides of the building, acting as thick walls that concealed the irregular angles of the lot, allowing the massive hall to take on a regular form. This hall serves both a smaller underground theater and a larger one suspended above it—conceived as a relatively autonomous volume supported by a set of oblique columns. In an expanded sense of the concept, one may suggest that this elevated volume functions as a giant poché for those who enter the building.

The almost contemporary Cine Ufa-Palácio, designed by Rino Levi in São Paulo in 1936, and the Cine Gran Rex, designed by Alberto Prebisch in Buenos Aires in 1937 (Borghini, Salama, & Solsona, 1987), were not built on awkward or irregular parcels but rather on regular ones (Figure 4). Yet both designs call upon the use of the poché to handle the discrepancy between the rectangular external volume of the building and the bowed shape of the movie hall—in the case of Rex—or the subtle inflections of interior spaces in Levi’s Ufa-Palácio. Levi’s symmetrical entrance space design, featuring two central columns set against a curved wall ending on both sides in generous circular volumes housing the ticket offices, improved by specially designed artificial lighting elements, recalls the Beaux-Arts meaning of the poché as expressive of character—something that could be even exaggerated or enriched to underscore the importance of the building (Figure 6).

Lina Bo Bardi, ever surprisingly, used the Brazilian varanda as a poché in her design for the Diários Associados Building (São Paulo, 1947, not built). The contradiction between the inside and the outside (to quote Venturi) is not transferred to the rear of the lot but resolved at the front, where Lina’s varanda acts as a buffer between the semicircular interior foyer and the exterior street (Figures 4 and 7).

The poché can also be observed in architectural works that might be seen as pieces of a “modern city” liberated from the traditional urban subdivision. Affonso Eduardo Reidy’s free-standing, wide, serpentine building at the Pedregulho Complex (Rio de Janeiro, 1946–1948), endowed with pilotis and free façades, also owes its meandering shape to the presumably forgotten poché. Reidy inserted thick walls between the dwelling units—sometimes used as cabinets—to absorb the internal angles produced by the curvature of the building and to preserve the regularity of the interior spaces (Figure 8).

Lastly, if we adhere to Rowe’s “overhauled” understanding of the poché—in which it is no longer limited to the inner part of a building—we could add to this list the plastic Covered Plaza by Carlos Raúl Villanueva (University City of Caracas, 1952–1953), which softly engages the inflected form of the Aula Magna and the orthogonal volume of the rectorate building.

The Poché and the Private Life of Buildings

As Reyner Banham put it, iron, steel, and concrete were new topics when they were incorporated into modern architecture, but “their general category was old and familiar. Not so electric lighting or mechanical ventilation” (Banham, 1984, p. 10). In the Beaux-Arts tradition, the poché was associated not only with a structural meaning but also—retrospectively—with a “functional” one. As already stated, the poché, understood as a shared graphic code, implied the existence of a reserved area, set aside for future construction and structural arrangements. In addition, it also denoted the placement of tiny service spaces inside these mostly opaque zones of masonry.

The poché holds a sort of “Janus-like quality,” borrowing Rowe’s term to define architectural elements that simultaneously express an objective functional purpose and evoke more open associations central to the idea of character (Rowe, 1976, p. 69). The poché was used by modern architects both to discipline and to hide the functional and mechanical components of buildings.

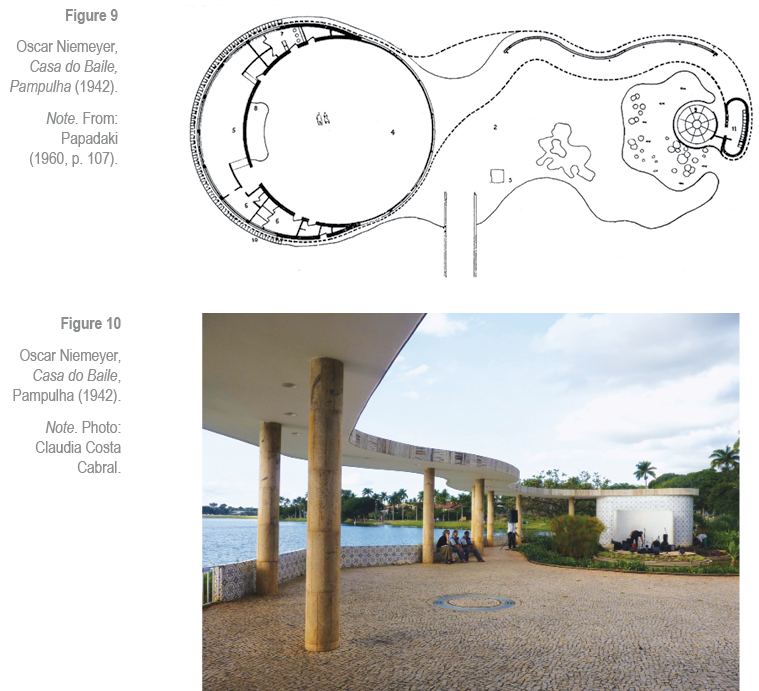

Oscar Niemeyer’s Casa do Baile (Pampulha, 1942) is well known for its singular ovoid shape, prolonged by a flowing concrete slab over pilotis. Niemeyer’s scheme overlapped two off-centered circles with slightly different diameters. The restaurant—the main space—was set in the smaller circle. The kitchen and service areas filled the crescent left between the two circles, functioning as a poché. This enabled the restaurant to be perceived as a free, neat round room from the inside, while preserving the unity of the whole external volume (Figures 9 and 10).

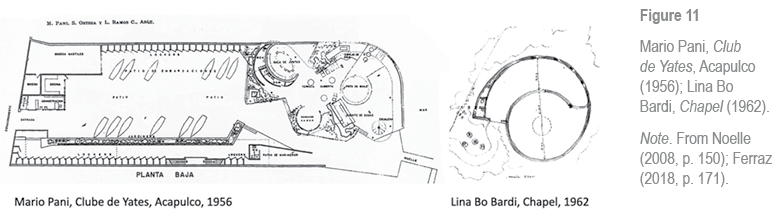

A similar use of the poché can be found in Mario Pani’s circular rooms in the Club de Yates in Acapulco (1956), as well as in Lina Bo Bardi’s 1962 study for a chapel (Figure 11). Later, Lina would once again appeal to the poché to accommodate the kitchen and service areas of the Restaurant Coaty in Salvador de Bahia (1986). The main space was a circular room built around an existing tree. The kitchen was placed in an adjacent circular volume, while the remaining services were pushed toward the rear, taking advantage of the marginal space between the circle and the straight edge of the lot (Figures 12 and 13).

Moreover, the notion of poché can be related to the condensed services cores functioning as solid interior volumes, as seen in Amancio Williams’s design for the UIA Building (Buenos Aires, 1968) and Mario Roberto Álvarez’s Somisa Building (Buenos Aires, 1966–1972) (Figure 14). In the symmetrical plan of the Somisa Building, which coincides with the triangular shape of the lot, lifts and service compartments are arranged along a central axis, enabling a free façade and a transparent interior space. Williams packed two mega-pillars, service shafts, toilets, stairs, and lifts into four equivalent volumes at the center of a released floor plan. Similarly, Clorindo Testa designed the four giant pillars of the Biblioteca Nacional (Buenos Aires, 1962–1995) as hollow structures, where he inserted lifts, toilets, service shafts, and so on (Figure 15). The service poché might also pop out as an exterior volume, as Antonio Bonet showed on the terrace of the Hostería La Solana del Mar (Portezuelo, 1946) (Figure 16).

As for the relatively new categories pointed out by Reyner Banham—plumbing, electric lighting, mechanic ventilation, and so forth—perhaps the most interesting example is the second expansion of the Museo de Bellas Artes in Caracas, carried out by Carlos Raúl Villanueva between 1966 and 1976 (Figure 17). The original building, constructed by Villanueva between 1935 and 1938, featured a symmetrical, Beaux-Art-inspired plan and a Neoclassical façade, despite the use of reinforced concrete columns covered with white mortar. Villanueva completed the first expansion of the building in 1952, keeping the original axial scheme and one-story height. In 1966, he enlarged the complex with a markedly different structure. He housed the new museum galleries in a resolutely modern five-story tower of exposed concrete, accessed by ramps (Castro, 2018). Following Louis Kahn’s precedent at the Yale University Art Gallery (1951–1953)—in which Kahn unified structure, installations, and ceiling into a reinforced concrete slab composed of hollow tetrahedrons—Villanueva designed the horizontal structure of the galleries tower as a structural and functional poché.

The tower was supported by four external walls of reinforced concrete. Each level housed a square exhibition room measuring 21 meters wide and four meters high, entirely free of interior columns. Villanueva developed a prefabricated system for the horizontal structure to be cast at the construction site. It was based on a regular three-by-three-meter grid and was composed of distinct types of elements: the so-called “frames,” used to form the ceiling; the “crosses,” found within the structure’s depth to connect the elements of the lower and upper cords; and the “plates,” which formed the flooring. Joined by post-tensioned cables, these pieces formed a three-dimensional grid 1,4 meters in depth (Castro, 2018). Villanueva explained the advantages of this thick yet semi-hollow structure, not only in terms of weight reduction but also for the space it provided for installations, lighting fixtures, fittings, among others, which could easily pass through the whole structure (Villanueva, 1966).

Conclusion

The poché was essential to an academic idea of composition in which structural and functional components could be condensed within an opaque masonry mass. Such opaqueness has also been described as the symptom of a design system that prioritized the figurative aspects of composition over the more practical ones—those related to construction and services—which were left to be specified at a later stage (Corona Martínez, 1990). From Laugier to the Bauhaus, the functionalist doctrine would contradict this practice, advocating instead for an architecture in which each part clearly expressed its constructive and functional role. As Barry Bergdoll has put it, Laugier’s allegory of the primitive hut—and his insistence that walls needed for protection but not for structural support should never be employed without showing “their artifice”—established “the ethical criteria of truth which would have a long life in modern architectural theory” (Bergdoll, 2000, p. 12).

As a design technique learned from the academic tradition, the poché may be seen as opposed to the clarity pursued by modern architecture. This subtle, understated persistence of the poché in the practice of modern architects in Latin America—as illustrated by the cases discussed here—reveals a resourceful, original, and inventive use of an old design tradition years before the ban against the use of history was lifted and the Beaux-Arts system inspired an extensive historiographical review by museums and scholars.4

The Beaux-Arts poché tradition may have had formal or even decorous motivations, but it was also objective and pragmatic. The many ways in which the poché was employed and reinvented over the years show the persistence of disciplinary knowledge. The history of architecture has emphasized ruptures rather than continuities. Sounding breakups and visible turns have been more profoundly interrogated and scrutinized than the plain and more or less unnoticeable persistence of the disciplinary techniques and the practical instrumentality of architecture as a profession.

Modern architecture embraced radical, revolutionary statements on structuring architectural space, hoping to shape new ways of thinking and comply with current social requirements. Academic tradition, by contrast, was probably more concerned with perfecting a system of stable—though not immutable—rules, rather than seeking to transcend them in search of a revolutionary future. Yet, as an “a-stylar” body of principles, as Colquhoun has put it, the Beaux-Arts system seems to have continued supplying modern architecture with useful ammunition in its long avant-garde battle.

References

Anelli, R., Guerra, A., & Kon, N. (2001). Rino Levi, arquitetura e cidade. Romano Guerra Editora.

Aymonino, C. (1984). O significado das cidades. Presença.

Banham, R. (1984). The architecture of the well-tempered environment (2nd ed). The University of Chicago Press.

Bergdoll, B. (2000). European architecture 1750–1890. Oxford University Press.

Borghini, S., Salama, H., & Solsona, J. (1987). 1930–1950 Arquitectura moderna en Buenos Aires. Nobuko.

Chafee, R. (1977). The teaching of architecture at the École des Beaux-Arts. In A. Drexler (ed.), The architecture of the École des Beaux-Arts (pp. 61–109). The Museum of Modern Art.

Colquhoun, A. (1986). Conflitti ideologici del moderno. Casabella, 520–521, 11–18.

Comas, C. E. (2006). Corollaire brésilien: l’architecture moderne et la tradition académique. Les Cahiers de la Recherche Architecturale, Urbaine et Paysagère, 18–19, 47–66.

Comas, C. E. (2019). Beaux-Arts y arquitectura en América Latina. Summa+, 172, 128.

Corona Martínez, A. (1990). Ensayo sobre el proyecto. CP67.

Cuadra, M. (2000). Clorindo Testa, architect. Nai Publishers.

de Castro, C. E. B. (2018). Paredes modernas, o Museu de Belas Artes de Caracas e o SESC Pompéia [Master’s thesis. Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul].

Dembo, N. (2011). La tectónica en la obra de Carlos Raúl Villanueva: aproximación en tres tempos. UCV.

Drexler, A. (Ed.). (1975). The architecture of the École des Beaux-Arts. The Museum of Modern Art.

Ferraz, M. C. (Ed.). (2018). Lina Bo Bardi. 4th ed. Romano Guerra Editora.

Gregotti, V. (1986). Costruire l’architettura. Casabella, 520–521, 2–5.

Harbeson, J. F. (1926). The study of architectural design, with special reference to the program of the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design. Pencil Points Press.

Hautecoeur, L. (1964). História geral da arte: da natureza à abstração (Vol. 3, S. Milliet, Trans.). Difusão Européia do Livro.

Jurado, M. (2007). Diez estudios argentinos: Mario Roberto Álvarez y Asociados. 1st ed. Arte Gráfico Editorial Argentino.

Katzenstein, E., Natanson, G., & Schvartzman, H. (1985). Antonio Bonet: arquitectura y urbanismo en el Río de la Plata y España. Espacio Editora.

Lueder, C. (2015). Poché: The innominate evolution of a Koolhaasian technique. OASE, 94, 124–131.

Mindlin, H. E. (1956). Modern architecture in Brazil. Reinhold Publishing Corporation.

Noelle, L. (Ed.). (2008). Mario Pani. UNAM, Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas.

Nouvel Opéra. Plan (2025, March 8). [Image]. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nouvel_Op%C3%A9ra._Plan_-_Charles_Garnier_-_btv1b53221329q.jpg

Palau, L. (1916, mayo). Proyecto de un mausoleo. Revista de Arquitectura, II(5), sección Estímulo de Arquitectura, lámina IV. https://biblioteca.fadu.uba.ar/catalogo/revistas/pdf.php?f=pdf/files/e50b85e708b77b8928006cb6824b086c&g=6

Papadaki, S. (1960). Oscar Niemeyer. George Braziller.

Peyre, J. & De Wailly, Ch. (1781). Plans du Théâtre de l'Odéon. Plan du rez de chaussée au niveau du parterre [Image]. Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris. https://bibliotheques-specialisees.paris.fr/ark:/73873/pf0001998045/v0001.simple.highlight=Cr%C3%A9ateur:%20%22Wailly,%20%20Charles%20de%20(1729-1798)%22.selectedTab=record

Romero, J. L. (2007). Latinoamérica: las ciudades y las ideas. Siglo Veintuno Argentina.

Rowe, C. (1976). The mathematics of the ideal villa and other essays. The MIT Press.

Rowe, C., & Koetter, F. (1979). Collage city. The MIT Press.

Solá, F. (1916, mayo). Proyecto de un mausoleo. Revista de Arquitectura, II(5), sección Estímulo de Arquitectura, lámina I. https://biblioteca.fadu.uba.ar/catalogo/revistas/pdf.php?f=pdf/files/e50b85e708b77b8928006cb6824b086c&g=6

Soto, R. (1916, mayo). Proyecto de un mausoleo. Revista de Arquitectura, II(5), sección Estímulo de Arquitectura, lámina I. https://biblioteca.fadu.uba.ar/catalogo/revistas/pdf.php?f=pdf/files/e50b85e708b77b8928006cb6824b086c&g=6

Szambien, W. (1986). L’avvento dell composizione architettonica in Francia. Casabella 520–521, 64–66.

Venturi, R. (1977). Complexity and contradiction in architecture. The Museum of Modern Art.

Villanueva, C. (1966). Ampliación del Museo de Bellas Artes en el Parque Los Caobos en Caracas. Memoria Descriptiva – Estructura. In C. E. B. de Castro (2018). Paredes modernas, o Museu de Belas Artes de Caracas e o SESC Pompéia [Master’s thesis. Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul], pp. 258–262.

Williams, C. (2008). Amancio Williams: obras y textos. 47 al fondo, 17, 30–31. http://bdzalba.fau.unlp.edu.ar/greenstone/collect/investig/index/assoc/AR174.dir/doc.pdf

Young, M. (2019). Paradigms in the poché. In A. Kulper, G. La, & J. Ficca (Eds.), 107th ACSA Annual Meeting Proceedings, Black Box (pp. 190–195).

1 This article is based on the paper “The Beaux-Arts Poché and Modern Architecture in Latin America,” presented at the 7th International Conference of the European Architectural History Network (EAHN 2022), held in Madrid, as part of the session “Mid-Century Modern Architecture and the Academic Tradition,” proposed and chaired by Carlos Eduardo Dias Comas (Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul) and Maria Cristina Cabral (Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro). I would like to acknowledge the chairs’ thematic proposal, which shaped the development of this paper, as well as the support of the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Brazil, for my research on modern architecture in Latin America.

2 For further discussion of the concepts of composition and character in relation to modern architecture in Latin America, see: Comas, C. E. (2006) Corollaire brésilien: l’architecture moderne et la tradition académique, Les Cahiers de la Recherche Architecturale, Urbaine et Paysagère, 18/19, 47–66; and Comas, C. E. (2019). Beaux-Arts y arquitectura en América Latina, Summa+, 172, 128.

3 On Rino Levi’s acoustic expertise see: Anelli, R., Guerra, A., & Kon, N. (2001). Rino Levi, arquitetura e cidade (1st ed., pp. 179–180). Romano Guerra Editora.

4 Although the presence of the poché in contemporary architecture could be explored—as other authors have shown (Lueder, 2015; Young, 2019)—we would not, strictly speaking, referring to the same phenomenon. The historiographical review of the academic tradition mediates between modern architecture and the contemporary scene. It poses a somehow different question that would require the assessment of a larger historiographical framework, which exceeds the aim of this article, centered on the knowledge of modern architecture.