THE MARGINALIZATION OF THE VISUAL

IN ARCHITECTURAL THEORY:

ORIGINS, CONSEQUENCES, AND CHALLENGES

La marginación de lo visual en la teoría

arquitectónica: orígenes, consecuencias y desafíos

Manfredo Di Robilant

Politecnico di Torino, Italia

Received: January 16, 2025

Accepted: April 10, 2025

doi: https://doi.org/10.26439/limaq2025.n016.7653

In most architectural theory books published in recent decades, words prevail while images remain sparse and secondary—if not entirely superfluous—to the arguments presented. These images often resemble relics from the formative decades of modern architecture, a time when architectural discourse was rich in iconography. Following the crisis of the modern movement, images were largely abandoned in architectural debate. For several decades now, architectural theory has primarily involved the introduction of philosophical trends into the field. As philosophy is minimally visual, words have come to dominate architectural theory. However, both designers and the general public predominantly engage with architecture through visualization. This article examines the origins and consequences of this hiatus and, through a research project conducted by the author, illustrates how ad hoc imagery can shape architectural arguments.

book design, iconography, philosophy and architecture, visual argumentation

En la mayoría de los libros de teoría arquitectónica publicados en las últimas décadas, las palabras predominan mientras que las imágenes son escasas y secundarias —cuando no superfluas— respecto a los argumentos expuestos. Estas suelen remitir a las décadas formativas de la arquitectura moderna, cuando el discurso era rico en iconografía. Tras la crisis del movimiento moderno, las imágenes fueron prácticamente abandonadas en el debate teórico. Desde entonces, la teoría arquitectónica se ha centrado en la incorporación de corrientes filosóficas, disciplina escasamente visual, lo que ha reforzado la primacía del texto. Sin embargo, tanto los proyectistas como el público experimentan la arquitectura principalmente a través de lo visual. Este artículo analiza los orígenes y consecuencias de esta situación y muestra, a partir de un proyecto de investigación del autor, cómo las imágenes ad hoc pueden dar forma a los argumentos arquitectónicos.

diseño editorial, iconografía, filosofía de la arquitectura, argumentación visual

This is an open access article, published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license.

INTRODUCTION

Theory in architectural practice has the potential to help architects and those in related fields—identify and address issues that are critical to our built environment.1 However, the form that theory takes is crucial to its effectiveness. When examining architectural thought produced since the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution, we encounter a wide range of theories. These theories can be colliding, complementary or extraneous to each other, depending on the backgrounds, interests, and ambitions of their authors, but all are expressed through written words. Many are also expressed—or at least clarified—through images.

In the following paragraphs, I trace a path through modern and contemporary architectural thought by focusing on the relationship between words and images in books or manifestos that have conveyed some of these theories. In doing so, I refer to physical objects: paper publications. I do not consider the content of these publications outside of the form in which they are presented. Therefore, I take into consideration aspects such as page size, graphic layout, the number and scale of the images, if the images were produced ad hoc or come from other sources, and so on.

I also examine the extent to which words and images are interrelated—that is, whether the discourse remains clear and persuasive if images are removed. As for the contents, my aim is not to provide a brief history of an entire cultural sector, but rather to highlight a specific process within it. Therefore, the selection of cases is limited to a set of exemplary instances.

FOUNDATIONAL CASES

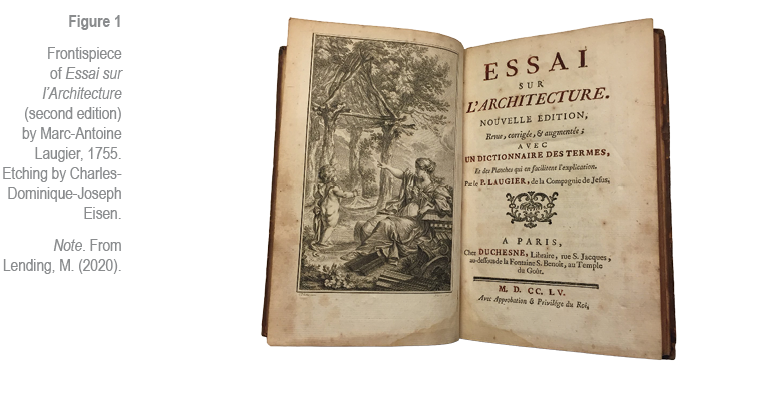

Among the architectural thinkers at the dawn of modernity is the French Marc-Antoine Laugier, who in 1753 published his Essai sur l’Architecture (Laugier, 1753). Laugier never practiced as an architect, with the exception of a consultancy for the design of the choir in the Cathedral of Amiens. When writing about architecture, he was thus not seeking commissions or attempting to establish a social status for himself, since he was already a high-ranking ecclesiastic. In his reflections on architecture, he offered readers guiding principles rather than examples of how to design buildings.

Conversely, books on architectural theory that spread across Europe following the invention of the printing press—beginning in the early sixteenth century—provided readers with concrete examples, ranging from individual elements such as columns or capitals to entire buildings like palaces or churches. All editions of works by Vitruvius, Vignola, de l’Orme, Palladio, and Scamozzi—to name a few—were intended to supply readers with visual samples to copy or draw inspiration from in their own work. The words in these books are often long captions for the illustrations; they are subordinated to iconography (Cosgrove, 2000).

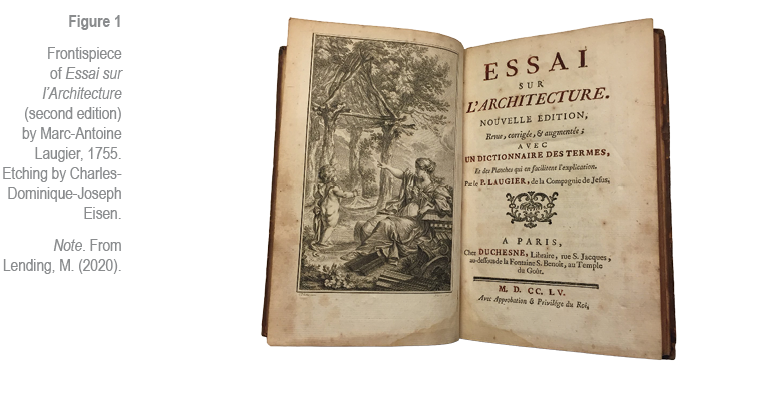

Though, Laugier’s words are independent from images, and his book was printed with not a single image in it, not even in the frontispiece. The usual sizes for architectural treatises were in-quarto or in-folio, so that the details of the drawings were visible; Laugier’s Essai was in-ottavo. Laugier’s ambition was to establish the foundational principles of architecture, from which operational rules could descend about how to design buildings. The idea that humans were happier and better in primitive societies was in fashion in contemporary philosophy in France, and Laugier individuated the foundational principles of architecture in the imitation of nature (Laugier, 1977). He argued that the origin of architecture was in a ‘primitive hut’ made by imitating trees. The trunks became columns, the branches became beams, and the leaves became tiles.

Already Vitruvius wrote about this primitive hut, but Laugier gave it an importance that Vitruvius did not. Laugier in fact could connect the ‘primitive hut’ to a contemporary philosophical fashion. He stated the primacy of thought in architecture: “It seems to me that in those arts which are not purely mechanical it is not sufficient to know how to work; it is above all important to learn to think” (Laugier, 1977, p. 1). For Laugier, the archetype was exclusively theoretic, a metaphor, a metonymy, a genetical principle, a verification criteria, and a logical operator (Laugier, 1987, pp. 14–15). Architecture, for him, was an occasion to express interests and apply persuasions that he had matured in another field. Goethe criticized him as a “connoisseur of philosophy” who tried to engage architecture (Laugier, 1987, pp. 7–8).

In 1755, Laugier published a second edition of his book, which included a preface addressing some of the critiques he had received and a concise dictionary of architectural terms, illustrated with eight schemes. However, what changed the posthumous destiny of Laugier was the etching, printed in full page at the left of the frontispiece: an allegory of nature showing the primitive hut to architecture. The drawing, created by Charles-Dominique-Joseph Eisen, strictly followed Laugier’s arguments and has become “one of the most celebrated icons in the history of architecture” (MIT Libraries, n.d.).

The paradox is that although Laugier’s book was conceived as a merely verbal, argumentative essay, it is a single image—external to the main text—that prevailed over nearly three hundred pages of arguments. This may serve as an indication that images are powerful persuasive tools in architectural discourse.

In exploring the relationship between words and images in architecture, an opposite to Laugier’s approach can be found in a book whose iconography also achieved wide diffusion—though its success was immediate, unlike the posthumous recognition of Laugier’s allegory. This is Augustus Welby Pugin’s Contrasts, published in 1836 with the ambition to expose the criticalities of industrial England by comparing its contemporary architecture with that of the Middle Ages (Pugin, 1836). The book’s subtitle reads: Or, a parallel between the noble edifices of the Middle Ages and corresponding buildings of the present day. However, what follows on the frontispiece is more interesting to this article’s purpose: Accompanied by appropriate text.

Pugin conceived his work as an iconographic demonstration of his thesis. The fifteen full-page images of architectural “contrasts” at the bottom of the in quarto volume—all produced ad hoc by the author—are self-evident in their goal. The fifty pages of the book that precede are “accompanying”. Pugin, a masterful illustrator and architect obsessed with detail, was not diminishing the value of words in general. Rather, in his self-appointed mission as a Catholic aiming to redeem Protestant industrial society, he recognized the power of icons, and specifically of architectural icons (Hill, 2009).

Therefore, he addressed his images not only to architects but also to policymakers operating within the architectural field, in an effort to promote reforms in society. Pugin might have appeared either too naïve or too sophisticated, but what is relevant to this article is that he addressed general topics using architecture as an advantage, visual point. In this sense, Pugin anticipated the early twentieth-century avant-garde fascination with manifestos, even though his project advocated a return to the past.

Another nineteenth-century theorist who anticipated avant-garde topics was Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, a French pioneer of preservation and author of, among other books, Entretiens sur l’architecture, published in two volumes and an accompanying album between 1863 and 1872, and later translated into English in 1881 (Viollet-Le-Duc, 1863). Entretiens sur l’architecture consists of 445 pages, illustrated with small in-text images, and aims to trace a broad compendium of architectural history while projecting its future in light of modernity. However, what contributed most to the book’s success were the 36 large, out-of-text drawings, engraved ad hoc by different illustrators under the author’s supervision. These images extended beyond words, particularly the iron construction projects, which functioned as “seeds disseminated for future developments” (Bressani, 2014, p. 432).

The success of Entretiens sur l’architecture was not unrelated to the fame of its author, a prominent public character during the Second Empire, but it was the iconography that played a crucial role in the book’s diffusion. Among the out-of-text images are some architectural fantasies of public buildings that combine iron frameworks and stone vaults. Viollet-le-Duc exerted significant influence on architecture thanks to these fantasies, even before his texts were translated into other languages, as the prominent English architect William Burges testified: “We all cribbed on Viollet-le-Duc even though no one could read French” (“Eugène Viollet-le-Duc,” 2024).

Without considering the role of the Entretiens sur l’architecture’s iconography, it is difficult to understand the twentieth-century architecture’s fascination with the metaphor of structure as the skeleton of buildings—and with other anatomical metaphors—along with their impact on both buildings and the lives of their inhabitants and users. Once again, the power of the image synthesized and overcame the verbal content.

Twentieth century MANIFESTOS

Sant’Elia and Le Corbusier

In the twentieth century, the protagonists of the modern movement frequently used images to formulate their ideas—an approach consistent with their contiguity to the visual arts, as already noted by Sigfried Giedion, theorist of the Congrès International d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM) (Giedion, 1941). Antonio Sant’Elia’s L’architettura futurista: Manifesto, published in 1914, is an eloquent example of this contiguity.

In terms of its material form, the manifesto is a four-page leaflet, approximately A4 in size. The first two pages contain only text, with key passages highlighted in bold; the third page is equally composed of text and images; and the fourth consists only of images, all drawn by the author himself. Words and images are not strictly interrelated: the six images serve as possible samples of what Futurist architecture might look like, extending beyond the text. Hence, reading the text is not necessary to understand the manifesto’s claim. Indeed, the images have been reproduced countless times without accompanying words, standing as autonomous theses on architecture (Sant’Elia, 1914).

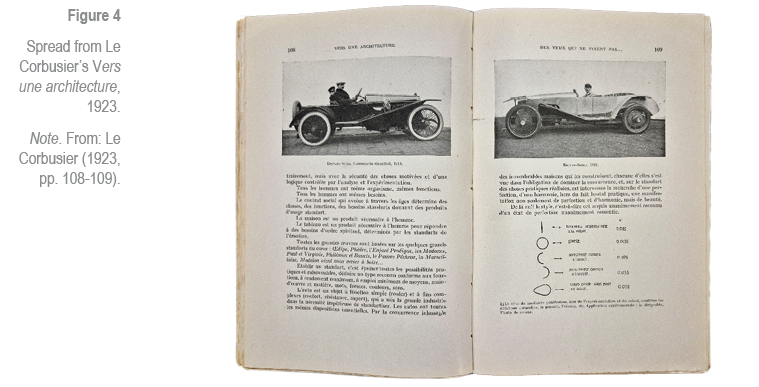

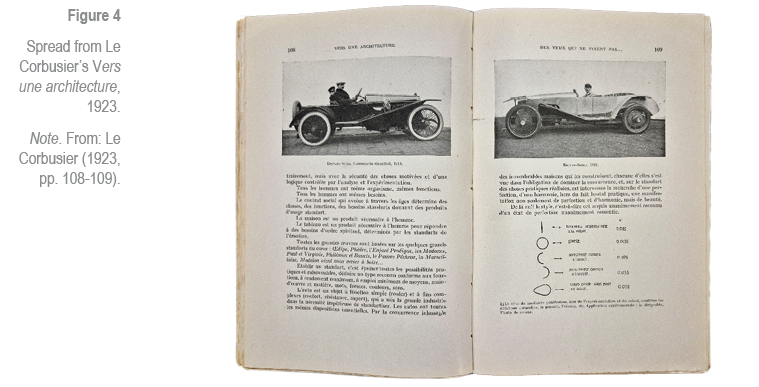

The Futurist visions remained paper architecture, but when Le Corbusier published his own manifesto, Vers une architecture, in 1923, he pursued the same iconicity through more nuanced means (Le Corbusier, 1923). Vers une architecture was charged with the same ambition that Sant’Elia infused in his leaflet, yet it took the form of a book.

Excluding the introductions to various editions and the epistolary appendix, the core text spans 243 pages and contains approximately 220 images. The book measures 240 × 150 mm, allowing the black-and-white images to remain clearly legible despite their low resolution. Apart from the first five pages—where the author outlines his key positions—and the opening page of each section, which introduces its main argument, the book includes only 24 pages of uninterrupted text and just three spreads without images. Le Corbusier designed the layout page by page, conceiving it visually rather than verbally (Cohen, 2016).

The images fall into several categories: photographs of buildings and other objects, drawings taken from external sources, and illustrations by the author himself. These images are closely integrated with the text, which is not meant to stand alone. The images serve to describe, compare, provoke, and demonstrate. Their close relationship with the text makes them eloquent: they are part of the argument. Le Corbusier used visuals to construct his arguments and words to elaborate on them. In Vers une architecture, the arguments are often communicated visually before the text is even read.

Gropius and the Bauhaus

The doctrine of Walter Gropius, another foundational character of modern architecture, was more visual than verbal when he was director of the Bauhaus in the 1920s. Still, he continued to assign a crucial role to images even when he published his ideas in book form. This was the case in 1935, when he left Nazi Germany and presented his positions in the United Kingdom and the United States. The New Architecture and the Bauhaus, published in London in 1935, is an octavo-format book of 112 pages, 14 of which are entirely visual and two partially so. Without these images, the text would lack supporting evidence (Gropius, 1965). Even in his most theoretically oriented book, Apollo in the Democracy: The Cultural Obligation of the Architect, published in 1968, images remain important for clarifying the ethical and political agenda he proposes (Gropius, 1968). Until the end of his life, Gropius remained consistent with the Bauhaus ideals—principles that were, quite literally, a vision rather than a series of argumentations.

Rudofsky and Venturi, Scott Brown, Izenour

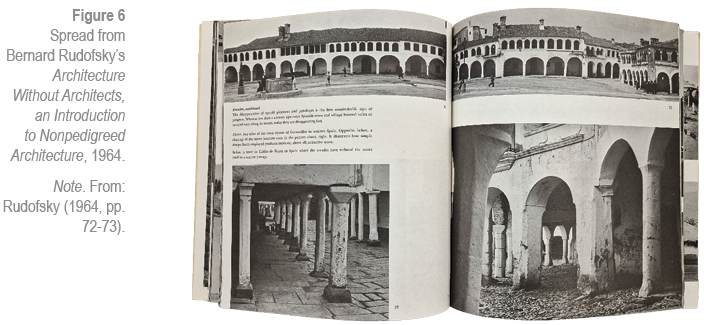

When, in the early 1960s, divergent positions started to emerge beyond the modern masters such as Le Corbusier and Gropius, much of the confrontation was conducted through colliding iconographies. A blatant example in this regard is Bernard Rudofsky’s Architecture Without Architects: A Short Introduction to Non-Pedigreed Architecture, the catalogue of an exhibition held at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1964–1965 and, as such, deeply visual in nature (Rudofsky, 1964). The book comprises 156 pages in an almost square format (240 × 215 mm) and contains 156 pages and 156 images, black-and-white photographs, with nine drawings. The images are large and dominate the layout of all pages, while the text consists of extended captions. The photographs themselves form the argument and, as the author states, are the output of lifelong research. They depict buildings and towns in rural contexts, many outside Europe and North America, all of which are non-authored.

The polemic targets the urban-focused, Eurocentric modern movement and its assumption that buildings ought to be designed by specialists and should reflect industrial progress and the emergence of new technologies. Despite its strong reliance on iconography, Architecture Without Architects is not a pamphlet; rather, it presents a strong methodological stance calling for anthropology to be considered as complementary approach to architectural thought. The prevalence of images does not necessarily imply a conception of architecture as an autonomous discipline.

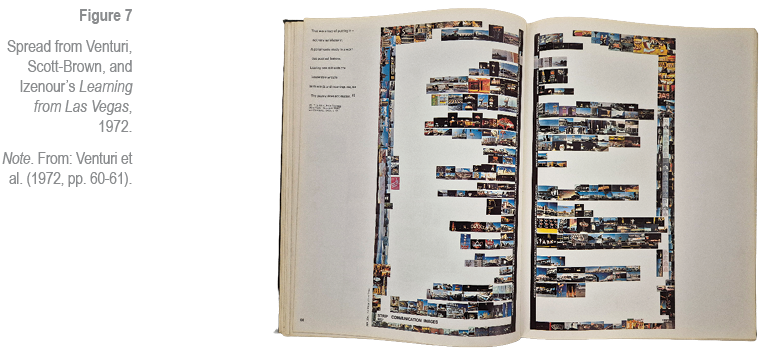

Less than a decade later, another blatant iconographic opposition to architectural specialization appeared: Learning from Las Vegas by Venturi, Scott Brown, and Izenour (Venturi et al., 1972). Its large format (355 × 265 mm) supports Muriel Cooper’s layout, which is designed around the extensive iconography of Las Vegas streets, accompanied by analytical sketches by the authors. It is now almost a cliché to describe Learning from Las Vegas as a milestone in the twentieth-century architectural literature; however, it is still worth emphasizing that the book emerged from the authors’ academic work, specifically a graduate research studio at Yale. Yet, because its visual arguments consist of photos and sketches, Learning from Las Vegas does not require specialized architectural training to be understood, despite the complexity of its arguments and regardless of whether one agrees with its conclusions.

POST-1960’S VERBALIZATION

Rossi and Tafuri

How many recent books by scholars in architecture have a comparable degree of universality? To understand why most of them seek hyper-specialization rather than universality, we must go back to the mid-1960s. A relevant case in this regard is Aldo Rossi’s L’architettura della città, published in 1966 and later translated into several languages, including a seminal edition by MIT Press in 1984 (Rossi, 1984). At the time, Rossi already had a small practice, but the immediate goal of the publication was academic, since it served him as a qualification to advance in his university career.

Although he was writing a book on the theory of architectural design, Rossi made large use of theories developed by geographers—a move that facilitated the book’s reception within academia as a “scientific” work, rather than a manifesto oriented toward practice. Reinforcing this position, L’architettura della città appeared in the catalogue of an academic publisher not primarily focused on architecture (Rossi, 1966). The book adopts a scholarly format (230 × 165 mm), with a total of 210 pages and 12 images, all sourced from existing publications. At the end of the volume, there is an iconographic section containing 37 images. However, iconography in this case provides useful references rather than visual arguments. The arguments are entirely verbal.

L’architettura della città stands out for the influence it exerted in the following decades within international academia. For this reason, its extensive engagement with geographic theories is noteworthy. Geography, with its emphasis on objectivity, provided Rossi with a tool in his effort to reframe architecture as a “science.” The next step was to transform architecture into a “critical discourse,” intellectualizing and politicizing it and eventually depriving it of intrinsic reasons of interest.

An emblematic example on this trend can be found in the work of another highly influential Italian scholar, Manfredo Tafuri, who in 1968 published Teorie e storia dell’architettura (Tafuri, 1968). Like Rossi’s work, Tafuri’s book would become widely disseminated within American academia in the following decades. At the time, Tafuri was a young scholar fully devoted to academia, having already abandoned architectural practice. He considered his work as purely intellectual, and as such, sought to preserve it from the commercial aspects inherent to the profession.

Teorie e storia dell’architettura is, in many ways, a self-portrait of the architect-intellectual as a cleric. It reflects Tafuri’s deep pessimism regarding architecture’s potential to play an effective role in society, as well as his messianic belief in an imminent communist era—though his writing remains vague about how, and to what extent, such an era might redeem architecture from its supposed superfluity. Tafuri set a precedent through his pessimism, broad cultural references, and political anathemas.

The book measures 205 × 132 mm and comprises 272 pages, with 20 images embedded in the main text. These images illustrate buildings or projects mentioned in the surrounding paragraphs. The selection of cases appears somewhat random: the images serve not as evidence but just to spare the reader the task of seeking out the referenced examples. They are not more than a little help. An appendix follows, containing 83 images with brief captions, arranged to illustrate each chapter. Most of these images do not directly correspond to the text but rather expand upon the topics in each chapter. In this way, the book separates words from iconography: words become “discourse,” while the images in the appendix form a sui generis graphic novel.

I am not here presenting Teorie e storia dell’architettura as a “first” but rather as a notable example of a book that uses architecture as a starting point for a discourse whose legitimacy does not lie in architecture but in the discourse itself or in political claims (Cohen, 2015). Tafuri was a Marxist, with sympathies for structuralism and semiotics, both of which he mentions in Teorie e storia dell’architettura. However, he did not frame his arguments within a systematic approach and always kept a degree of methodological eclecticism in his subsequent works.

Deconstructivism

The step forward—namely, the attempt to systematically frame architectural discourse within a specific philosophical current—emerged later, when American academia became fascinated by French philosophy, with Jacques Derrida as a flag bearer (Cusset, 2008). A seminal manifestation of this trend in architecture occurred in the mid-1980s, with the exchange of letters between Peter Eisenman and Jacques Derrida (Kipnis & Leeser, 1997). As a designer, Eisenman tried to transform Derrida’s words into spatial visions; however, in architectural jargon, “deconstructivism” became de facto a word to define a style in a paradoxical coming back of early twentieth-century reine Sichbarchkeit. The exhibition Deconstructivist Architecture, held at the MoMA in 1989, marked the “architecturalization” of the word, overlooking its philosophical origin while linking it to Russian constructivism.

This “architecturalization” could be considered as a case of intellectual appropriation and creative exploitation of work from another field. However, in fact, it seems it had the opposite effect: it legitimated architects’ aspirations to try turning into philosophers. Since philosophy is scantly visual, words prevailed over images in architectural theory books. An example of pure iconoclasm can be found in Mark Wigley’s The Architecture of Deconstruction: Derrida’s Haunt, published in 1993 (Wigley, 1995). In this discussion of the implications that the thought of Derrida might have on architecture—and vice versa—there are no images. The only image is on the cover but does not directly reference architecture, as it depicts a mousetrap. Wigley, who was co-curator of the MoMA exhibition, could perhaps be seen as attempting to compensate for the centrality of images in the exhibition itself. In a balance between images and words, the 1990s witnessed a marked shift toward the latter in academic publications on architectural thought.

Pérez-Gomez, Hays, Leach and Pallasmaa

Numerous examples from this decade illustrate the diminishing relevance of images. One particular fascinating case is a book by Alberto Pérez-Gomez, one of the academic initiators of the liaison between philosophy and architecture, and himself trained in architecture. In his Polyphilo or the Dark Forest Revisited: An Erotic Epiphany of Architecture, published in 1992, the images are not related to the text. Much like in Teorie e storia dell’architettura, they form a sui generis graphic novel, with the difference that they have nothing to do with architecture (Pérez-Gómez, 1992). It is rather surprising that the title references the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, the Venetian folio book published in 1499, which constituted a milestone in the intertwining between text and images. The tendency toward verbal suprematism was consolidated at the end of the century in a climactic and influential 800-page volume by Michael Hays, published in 1998 and released in paperback two years afterward. Hays, a professor of Architectural Theory at Harvard, conceived Architecture Theory since 1968 as an anthology for students and scholars (Hays, 1998). Among the authors are not only writers but also practicing architects who have had a profound influence on the field, including Tschumi, Eisenman, Stern, Koolhaas, and Krier. There is substantial architectural content in the book. However, its operation is the opposite of the catalogue of Deconstructivism in Architecture: it “philosophizes” architecture by framing it within a complex and multilayered system of philosophical trends. In Hay’s anthology, architecture is positioned as following philosophy, and readers—typically architecture students—are expected to learn about philosophy in order to understand architecture.

Accordingly, images are extremely rare occurrences within the densely printed pages, which measure 200 × 280 mm. With its thickness and bright red cover, Architecture Theory since 1968 stands as a bibliographical monument to a trend that consolidated in the following years, marking the marginalization of architects—and of architectural tools and contents—from academic publications on architectural theory.

In a book published the year after Hays’ anthology, theorist Neil Leach addresses The Anaesthetics of Architecture, in which he complains about the condition of architecture at the turn of the century (Leach, 1999). He criticizes the contamination of architecture by “the intoxicating world of the image,” which he links to the free market and seems to abhor (Leach, 1999, p. 1). Unsurprisingly, one of his targets is Learning from Las Vegas, with its iconography that celebrates commercial billboards. Consistently with the new canon of architectural thought, Leach addresses this issue through philosophical theories, specifically those of Guy Debord and Jean Baudrillard. Of the book’s 98 pages, 34 contain images, but only seven depict particular buildings or architectural drawings. Except for two photos of the National Gallery’s expansion by Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, the images serve to support a discourse that is external to architecture itself.

The lasting influence of Tafuri’s pessimism remains evident. In the first two decades of the 21st century, the import of philosophical currents into architectural thought diffused as a given practice. A paradigmatic example is the current collection of nineteen books and e-books in Routledge’s Thinkers for Architects book series, aimed at architecture students.2 The series is premised on the implicit assumption that architects cannot be thinkers, so they need to be nourished by thought from outside their discipline. This thought is neither visual nor spatial. Yet the ability to visualize spatial solutions is fundamental to architecture at any scale. Despite the speculations of scholars who have left architecture to cultivate philosophy, when a new building enters the public realm, reactions are largely prompted by aesthetics and so by the visual. The question is that visualizing spatial solutions is a fundamental task of architecture at any scale.

The de-visualization of architectural theory has a manifesto in the seminal The Eyes of the Skin published by Juhani Pallasmaa (Pallasmaa, 1996), where the author reckons the importance of other senses than sight to understanding and designing buildings. The book itself features a thoughtful use of images, but the pars destruens of it is iconoclastic: “As a consequence of the current deluge of images, architecture of our time often appears as a mere retinal art, thus completing an epistemological cycle that began in Greek thought and architecture” (p. 24). The first target of Pallasmaa is the reduction of architecture to a collection of photos, so the shift from spatial to superficial (in literary and metaphorical sense) thought. The second target is the prevalence of the visual in architectural theory since Leon Battista Alberti. The contempt of the visual is also a characteristic of much of the philosophy that permeated architectural theory in the same years, again with Derrida as a flag bearer (Jay, 1993). But, I argue, the marginalization of the visual brought to a reversal of what was the aim of architectural thought before: addressing general topics using architecture as a vantage point.

Borissavliévitch and Koolhaas

In the trajectory that I traced until now, one could notice the missing of mostly verbal books on the theory of architecture before the 1960s or of others significantly visual after the same decade. Among the first, an example is the ambitious book by Serbian architect Miloutine Borissavliévitch, Les théories de l’architecture: Essai critique sur les principales doctrines, relatives à l’esthétique de l’architecture, published in the 1920s—the same decade in which Le Corbusier was spreading his visuals—but which remained confined to a niche audience (Borissavliévitch, 1926). Moreover, the author’s focus on theories of proportions makes some of the few images necessary to the chapters in which they appear.

Among the latter, two pervasively influential works stand out: Rem Koolhaas’ Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan (Koolhaas, 1978) and S, M, L, XL (Koolhaas et al., 1997). Their powerful, largely ad hoc visuals and bold graphic design make them projects in themselves; not merely vehicles for conveying architectural content. For this reason, these two books offer an example of how architectural thought can be produced through architectural means, rather than beyond or apart from them. However, I would argue that this feature of the two books has been largely overlooked by scholars in theory who, conversely, are often blind to architecture in the same schools dedicated to its teaching.

More broadly speaking, iconography is largely overlooked by academics engaged in architectural theory. The questions it raises and the potential it offers are ignored or disregarded. As a result, architectural theory has increasingly become a verbal exercise, conducted by scholars who are not primarily interested in architecture.

RECLAIMING THE VISUAL IN ARCHITECTURAL THEORY

To address this condition, I designed a series of projects for fantastic buildings, each of which discusses how a specific theme influences architecture (and vice versa, in some cases), like “proportions”, “control”, “progress”, “creativity”, “ethics” et alia. Each discussion is divided into paragraphs, and each paragraph is prompted from a zoom into the project. Architecture, even though fantastic, prompts arguments, and the visual prompts the verbal. The discussions become meta-projects. To make the discussions accessible, the projects are inspired by stories from the world’s literary canon.

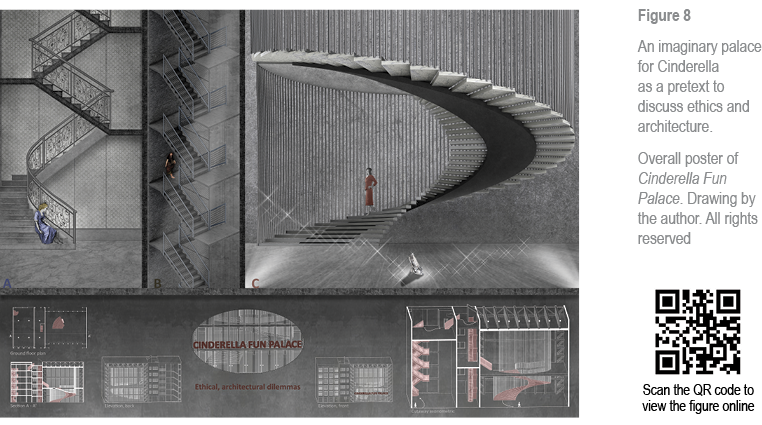

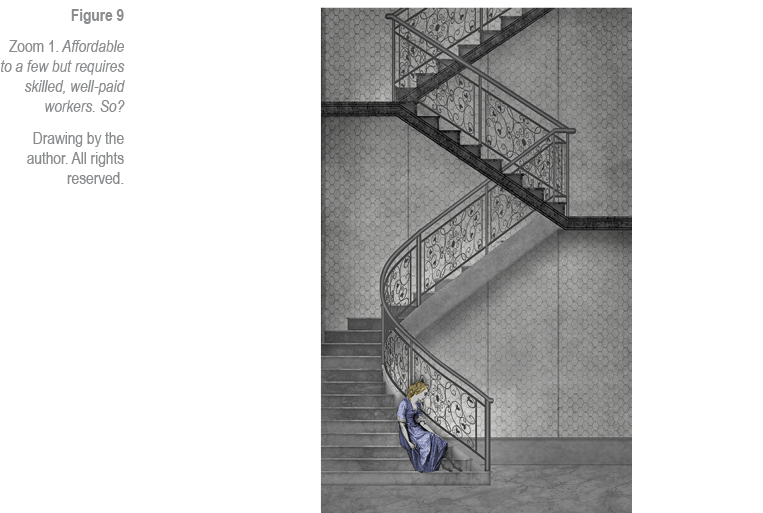

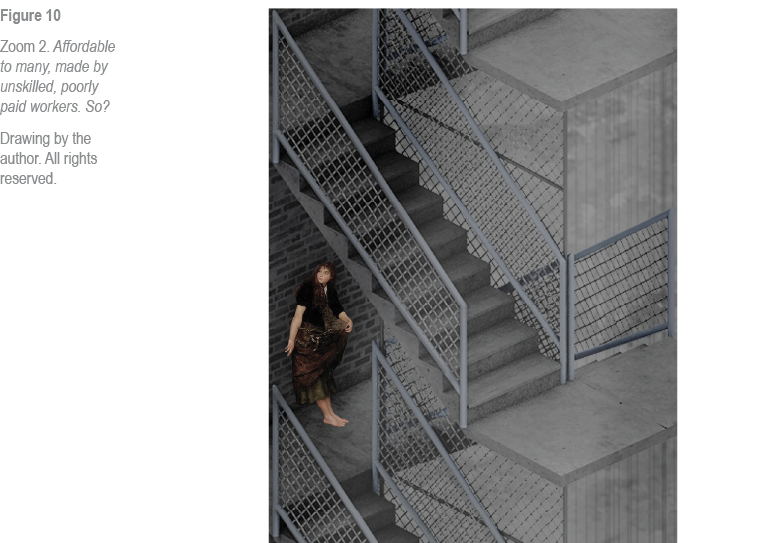

In the case of “ethics,” for example, the project is spun from the story of Cinderella—a tale of social descent and ascent, whose turning point takes place on a staircase. The project imagines a palace with three different staircases, each representing a significant rise or fall in Cinderella’s life: an archetype who loses everything only to gain the world, transitioning from her upper-class childhood to an enslaved adolescence, and ultimately to royal ascension. Each staircase incorporates architectural features that symbolically reflect its corresponding life stage. The discussion starts with the hypothesis that an aging Queen Cinderella has commissioned the palace to commemorate the anniversary of her despotic reign—something that, in real life, might resemble an autocracy. The palace is conceived as a monumental, functionless box. This leads to a provocative question: Should such a commission pose an ethical problem for the architect?

The discussion unfolds through six zoom-ins of the fictional project aimed at making architectural theory accessible to a wider audience. The following figures illustrate the six zoom-ins and key moments from the fictional project. Each illustration prompts a chapter, whose title is reported here as a caption, in form of a question. The full story forms a chapter of twelve from a book on which I am working, titled Projected Stories. 12 architectural discussions from 12 works of literature. The project is based on a narrow intertwining between images and words, in the attempt to define a visual and narrative approach to theory of architecture.

REFERENCES

Borissavliévitch, M. (1926). Les théories de l’architecture: Essai critique sur les principales doctrines, relatives à l’esthétique de l’architecture. Payot.

Bressani, M. (2014). Architecture and the Historical Imagination: Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-Le-Duc, 1814–1879. 1st ed. Ashgate. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315567679

Cohen, J. L. (2015). La coupure entre architectes et intellectuels, ou les enseignements de l’Italophilie: Ouvrage de référence sur l’architecture. Mardaga.

Cohen, J. L. (2016). Introduction. In Le Corbusier, Toward an Architecture (pp. 1–78). Frances Lincoln.

Cosgrove, D. (2000). Ptolemy and Vitruvius: Spatial representation in the sixteenth-century texts and commentaries. In A. Picon, & A. Ponte (Eds.), Architecture and the sciences: Exchanging metaphors (pp. 20–51). Princeton Architectural Press.

Cusset, F. (2008). French theory: How Foucault, Derrida, Deleuze, & Co. transformed the intellectual life of the United States. University of Minnesota Press.

Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. (2024, November 18). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Eug%C3%A8ne_Viollet-le-Duc&direction=prev&oldid=1264330365

Giedion, S. (1941). Space, time and architecture: The growth of a new tradition. Harvard University Press.

Gropius, W. (1965). The new architecture and the Bauhaus. The MIT Press. https://monoskop.org/images/b/b7/Gropius_Walter_The_New_Architecture_and_the_Bauhaus_1965.pdf

Gropius, W. (1968). Apollo in the democracy: The cultural obligation of the architect. McGraw-Hill.

Hays, K. M. (1998). Architecture theory since 1968. The MIT Press. Hill, R. (2009). God’s architect: Pugin and the building of romantic Britain. Yale University Press.

Jay, M. (1993). Downcast Eyes: The Denigration of Vision in Twentieth-Century French Thought. University of California Press.

Kipnis, J., & Leeser, T. (Eds.). (1997). Chora L Works: Jacques Derrida and Peter Eisenman. The Monacelli Press.

Koolhaas, R. (1978). Delirious New York: A retroactive manifesto for Manhattan. Oxford University Press. https://monoskop.org/images/8/81/Koolhaas_Rem_Delirious_New_York_A_Retroactive_Manifesto_for_Manhattan.pdf

Koolhaas, R., Mau, B., & Werlemann, H. (1997). S,M,L,XL. The Monacelli Press.

Laugier, M.-A. (1753). Essai sur l’architecture. Duchesne.

Laugier, M.-A. (1977). An essay on architecture. Hennessey & Ingalls.

Laugier, M.-A. (1987). Saggio sull’architettura. Aesthetica.

Le Corbusier (1923). Vers une architecture. Crès.

Leach, N. (1999). The anaesthetics of architecture. The MIT Press.

Lending, M. (2020). Origins in translation. Drawing Matter. https://drawingmatter.org/origins-in-translation/

MIT Libraries. (n.d.). Essai sur l’architecture (second edition), The Primitive Hut. DOME: MIT Libraries Visual Collections. https://dome.mit.edu/handle/1721.3/5422

Pallasmaa, J. (1996), The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. Academy Editions. (p.33, in third edition 2012), Wiley.

Pérez-Gómez, A. (1992). Polyphilo or the dark forest revisited: An erotic epiphany of architecture. The MIT Press.

Pugin, A. W. N. (1836). Contrasts: Or, a parallel between the noble edifices of the Middle Ages and corresponding buildings of the present day. Printed for the author. https://books.google.com.pe/books/about/Contrasts.html?id=vKRWAAAAMAAJ&redir_esc=y

Rossi, A. (1966). L’architettura della città. Marsilio.

Rossi, A. (1984). The architecture of the city (D. Ghirardo & D. Ockman, Trans.). The MIT Press. (Original work published 1966) https://monoskop.org/images/1/16/Rossi_Aldo_The_Architecture_of_the_City_1982_OCR_parts_missing.pdf

Rudofsky, B. (1964). Architecture without architects, an introduction to nonpedigreed architecture. The Museum of Modern Art. https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_3459_300062280.pdf

Sant’Elia, A. (1914). L’architettura futurista: Manifesto. https://eng.antoniosantelia.org/files/pdf/eng/manifesto_santelia.pdf

Tafuri, M. (1968). Teorie e storia dell’architettura. Laterza.

Venturi, R., Brown, D. S., & Izenour, S. (1972). Learning from Las Vegas. The MIT Press. https://monoskop.org/images/archive/c/cd/20170506121429%21Venturi_Brown_Izenour_Learning_from_Las_Vegas_rev_ed_missing_pp_164-192.pdf

Viollet-Le-Duc, E.-E. (1863). Entretiens sur l’architecture. Morel et Cie.

Wigley, M. (1995). The architecture of deconstruction: Derrida’s haunt. The MIT Press. https://monoskop.org/images/6/64/Wigley_Mark_The_Architecture_of_Deconstruction_Derridas_Haunt_1993.pdf

1 By “theory,” I refer to “The body of generalizations and principles developed in association with practice in a field of activity (such as medicine or music) and forming its content as an intellectual discipline” (Merriam-Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary, n.d.).

2 For an overview of the editorial presentation and series titles, see: https://www.routledge.com/Thinkers-for-Architects/book-series/THINKARCH?gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQiAsOq6BhDuARIsAGQ4-zjxywzPFEaiuFhnjBdDl06Vvet1dVYGqqzGA9c9ju2u9kWMmby1NIQaAmuxEALw_wcB