Computer vision for Pokémon Battles:

A YOLO and Tesseract-Based System

for Automated Recognition and Gameplay

Analysis

Miguel R. Lladó

https://orcid.org/0009-0001-1123-895X

Universidad de Lima, Perú

Terence Morley

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7588-6457

University of Manchester, United Kingdom

Received: September 11, 2025/ Accepted: November 6, 2025

doi: https://doi.org/10.26439/interfases2025.n022.8270

ABSTRACT. Pokémon Double Battles present a complex decision-making environment that has traditionally relied on manual data analysis. This paper introduces an automated system leveraging computer vision and deep learning to extract structured gameplay data from battle footage. Our approach integrates You Only Look Once (YOLO) for Pokémon sprite recognition along with Tesseract-based optical character recognition (OCR) for extracting move and status text. The study introduces a custom-built image dataset generated through the augmentation of publicly available Pokémon sprites, which is then used to train a YOLO model for sprite recognition. The system was tested across multiple controlled and real-world gameplay scenarios, achieving high accuracy in Pokémon recognition and action tracking. Additionally, a JSON-based gameplay notation system is proposed to structure battle sequences, thus improving analysis and strategic review. The results demonstrate the feasibility of AI-driven gameplay analysis, with potential applications for competitive players, game analysts, and developers. Given its exploratory nature, this study focuses on technical feasibility rather than statistical generalisation. Future work includes expanding the dataset, improving OCR performance, and enabling real-time processing to support broader practical use.

KEYWORDS: Computer vision, Pokémon, YOLO, Tesseract, OCR

Visión por Computador para Batallas Pokémon: Un Sistema

Basado en YOLO y Tesseract para el Reconocimiento

Automatizado y el Análisis de Juego

RESUMEN. Las batallas dobles de Pokémon presentan un entorno de toma de decisiones complejo que tradicionalmente ha dependido del análisis manual de datos. Este artículo presenta un sistema automatizado que aprovecha la visión por computadora y el aprendizaje profundo para extraer datos estructurados del metraje de batalla. Nuestro enfoque integra You Only Look Once (YOLO) para el reconocimiento de sprites de Pokémon y reconocimiento óptico de caracteres (OCR) con Tesseract para la extracción de movimientos y estados. El estudio presenta un conjunto de datos de imágenes personalizado, generado mediante la ampliación de sprites de Pokémon disponibles públicamente, y lo utiliza para entrenar un modelo YOLO para el reconocimiento de sprites. El sistema se probó en múltiples escenarios controlados y de juego real, logrando alta precisión en el reconocimiento y seguimiento de acciones. Además, se propone un sistema de notación basado en JSON para estructurar las secuencias de batalla, mejorando el análisis y la revisión estratégica. Los resultados demuestran la viabilidad del análisis de juego basado en IA, con aplicaciones potenciales para jugadores competitivos, analistas de videojuegos y desarrolladores. Dada su naturaleza exploratoria, este estudio se centra en la viabilidad técnica más que en la generalización estadística. Las mejoras futuras incluyen la expansión del conjunto de datos, la optimización del OCR y la integración de procesamiento en tiempo real para un uso más amplio.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Visión por computadora, Pokémon, YOLO, Tesseract, OCR

INTRODUCTION

Background and Motivation

Artificial intelligence (AI) has become increasingly influential in the video game industry, with applications ranging from non-player character (NPC) behaviour to advanced game analytics. In particular, computer vision, a subfield of AI focused on interpreting visual information, enables systems to analyse images and video to extract actionable insights. These capabilities are increasingly applied to optimize gameplay strategies, monitor player performance, and provide viewers with enriched information overlays during broadcasts (El-Nasr et al., 2016; Yannakakis & Togelius, 2018).

Pokémon, a video game franchise with hundreds of millions of sales (The Pokémon Company, 2024b), has integrated AI to improve both player experience and viewer engagement. For instance, the Pokémon Battle Scope (PBS), developed in collaboration with the Japanese AI company HEROZ (Takahiro & Tomohiro, n.d.), has been used to augment tournament broadcasts by providing real-time strategic feedback during Single Battles (The Pokémon Company, 2024d).

However, PBS focuses exclusively on Single Battles (1v1). In contrast, Double Battles—the official format of competitive tournaments including the Pokémon World Championship—feature two Pokémon per player, significantly increasing the number of possible move combinations, synergies, and strategic options (The Pokémon Company, 2024c). Analysing Double Battles presents new challenges and opportunities for applying AI and computer vision. Figure 1 illustrates the layout of a Double Battle, where both players command two Pokémon simultaneously.

Figure 1

Gameplay Image of a Double Battle as Displayed in the Video Game Pokémon Scarlet

Note. Image captured from the video game Pokémon Scarlet on Nintendo Switch.

This paper combines YOLO—a family of real-time vision models capable of detection, segmentation, and classification (Jocher et al., 2024; Redmon et al., 2016)—with Tesseract OCR (Tesseract OCR, n.d.-b) to automatically extract structured data from Pokémon Double Battle footage. In our pipeline, YOLO is used in its image-classification configuration to recognise Pokémon sprites, while Tesseract extracts on-screen text. The outputs are serialised into a JSON-based battle notation suitable for downstream analysis.

The study advances computer vision-based gameplay analysis by delivering, to our knowledge, one of the first systems that integrates YOLO and Tesseract OCR for the automated interpretation of Pokémon Double Battles. In contrast to prior work focused on single-battle settings or text-based simulations (Hu et al., 2024; Norström, 2019; Simoes et al., 2020), we demonstrate that deep learning can derive machine-readable structure directly from raw gameplay video. The resulting JSON notation offers a reusable foundation for player training, game analysis, and strategy review.

Research Aim and Objectives

The central aim of this study is to design and evaluate an image recognition system for Pokémon Double Battles, capable of transforming gameplay footage into structured data. This work supports the broader goal of enhancing the analytical capabilities available to players, developers, and researchers.

The paper focuses on three core objectives:

- Developing an image recognition pipeline using YOLO for Pokémon identification and Tesseract for move extraction.

- Creating and curating a labelled dataset of commonly used competitive Pokémon sprites, ensuring accurate model training.

- Implementing a JSON-based notation system to represent each turn in a structured and analysable format.

These components aim to reduce the need for manual analysis and pave the way for more advanced AI-driven tools that support gameplay insight, performance evaluation, and competitive training.

RELATED WORK

AI has been widely applied to video games for purposes ranging from gameplay enhancement to player modelling and opponent simulation. In the context of Pokémon, most academic research has focused on decision-making strategies using structured, text-based battle logs rather than analysing the game’s visual content (Yannakakis & Togelius, 2018).

For example, Simoes et al. (2020) developed a reinforcement learning agent capable of predicting optimal actions based on Pokémon Showdown simulations, which provides structured representations of in-game states. These models benefit from direct access to internal data such as team composition, moves, and health, making them easier to train. However, they do not address the challenge of interpreting battles from unstructured visual inputs such as gameplay video, particularly within the Pokémon franchise, where the interface presents multiple simultaneous visual elements, including Pokémon sprites, health bars, names, and move animations, that overlap and change dynamically each turn. While these earlier works relied on structured or simplified data sources (Hu et al., 2024; Norström, 2019), this study advances the field by analysing native gameplay footage from Double Battles, which introduces higher visual density and variability.

One of the most prominent commercial implementations of AI in Pokémon is the PBS, developed by The Pokémon Company in partnership with HEROZ and showcased in 2024 during official tournament broadcasts (The Pokémon Company International, 2024). PBS was used during Single Battle matches to provide real-time statistical overlays for viewers, such as indicators of which side held the advantage and suggestions for optimal moves based on the current battle context. Its primary goal was to enhance the viewing experience and make competitive matches more accessible to audiences unfamiliar with the strategic depth of the game. Nevertheless, PBS was only implemented for Single Battles, leaving the Double Battle format—used in official competitions such as the Pokémon World Championship—without equivalent analytical support (Heroz, 2024; The Pokémon Company, 2024c, 2024d).

Computer vision techniques offer a path forward for addressing this gap. Technologies such as YOLO (Redmon et al., 2016) have been widely adapted beyond object detection to perform image classification tasks, leveraging convolutional architectures trained to differentiate among visual categories (Redmon et al., 2016). This makes YOLO suitable for sprite recognition in games, where clear and repeatable visual patterns can be learned efficiently. Meanwhile, Tesseract OCR has proven effective for extracting text from images and video, including user interfaces and in-game overlays, though its performance depends on resolution, font clarity, and video quality (Smith, 2007; Tesseract OCR, n.d.-b).

The combined use of deep learning–based visual models and OCR has been explored in domains such as automatic number plate recognition, where YOLO variants are used to localise plates and Tesseract OCR (or similar engines) is applied to transcribe the characters. Examples include systems based on YOLOv5 combined with Tesseract OCR for real-time licence plate recognition, and YOLOv8 integrated with OCR techniques for high-precision plate detection and reading (Moussaoui et al., 2024; Thapliyal et al., 2023). These studies demonstrate how visual classification and detection, combined with OCR, can transform raw imagery into structured, machine-readable data—a methodological principle that can be applied.

While several studies have applied YOLO models to video game environments—such as first-person shooter scenarios for real-time character detection (Cheng, 2023) and object recognition using Grand Theft Auto V datasets for computer vision training (Bazan et al., 2024)—none have explored the integration of YOLO as an image classifier with Tesseract OCR to extract structured gameplay information within the Pokémon franchise. This study addresses such gap by testing a pipeline that classifies Pokémon sprites and extracts text-based actions from screen recordings. The extracted data is structured into a JSON-based notation system, providing a foundation for further gameplay analysis and AI-driven tools.

METHODOLOGY

This section outlines the development process of a system designed to extract structured data from Pokémon Double Battle gameplay using computer vision techniques. The methodology covers three main components: a YOLO-based sprite classification model, a Tesseract OCR-based text extractor, and a JSON-based battle notation system. Each component was developed to support the automation of battle interpretation and strategic data representation. The research is exploratory, aiming to validate the technical feasibility of the proposed recognition pipeline rather than produce generalisable performance metrics.

Pokémon Sprite Dataset and Classification Model

To train the image classification model for identifying Pokémon, a custom non-public sprite dataset was constructed based on Pokémon usage data from the 2024 North America Pokémon VGC International Championship (The Pokémon Company, 2024a). Only Pokémon with a usage rate above 1% were included, resulting in 62 unique sprites. This count reflects cases like Urshifu, whose different forms share identical in-game visuals.

Each sprite was sourced from pokemondb.net (Pokémon Database, 2024), resized to 256×256 pixels, and subjected to extensive augmentation to increase variability and simulate real-world conditions during Team Preview. Augmentation techniques applied included:

- Gaussian blur

- motion blur

- affine transformations (±5° rotation and ±5% scaling)

- additive Gaussian noise

- gamma contrast adjustment

- padding and cropping

Each Pokémon class produced 1,000 augmented images, split into 800 training, 100 validation, and 100 test samples, for a total of 62,000 images. Figure 2 illustrates a comparison between a base sprite and one of its augmented versions.

Figure 2

Original and Augmented Sprites of the Pokémon Urshifu

Note. Adapted from “Pokémon Sprite Archive,” by Pokémon Database, 2024 (https://pokemondb.net/sprites). Copyright Pokémon Database.

The classification model used for sprite recognition was YOLOv8m, a medium-sized image classifier comprising 103 layers and 15,842,078 parameters, operating at 41.7 GFLOPs (Jocher et al., 2024). Training was carried out using the Ultralytics (Ultralytics, 2024) classification pipeline with default hyperparameters. Once trained, the model was used to classify sprites displayed during the Team Preview phase of each recorded battle. The predicted Pokémon names were recorded in the system’s JSON-based battle notation as the opposing team’s composition.

Gameplay Footage Collection

To validate the system under real gameplay conditions, footage from eight complete Pokémon Double Battles was recorded using the Nintendo Switch version of Pokémon Scarlet. All matches followed the VGC Regulation Set G, the official competitive format used in ranked online play (The Pokémon Company, 2024c). The sample size was defined to balance the diversity of competitive scenarios with the practical constraints of manual frame annotation and model validation. Each recorded battle contained multiple visual events—including move executions and Pokémon switches—providing a sufficiently varied dataset for evaluating classification accuracy and OCR performance within exploratory research context. Figure 3 illustrates the main gameplay phases captured during each recorded Double Battle, which guided the segmentation of the validation process described in the following sections.

Figure 3

Simplified Sequence of Gameplay Phases in Pokémon Scarlet Double Battles Used for System Validation

Note. Gameplay images from the video game Pokémon Scarlet on Nintendo Switch.

Video capture was performed using an Elgato 4K X capture card (Elgato, 2024) in combination with OBS Studio, version 30.1.1 (OBS Project, 2024), ensuring consistent image quality across all the recordings. Each video was exported at a resolution of 1920×1080 pixels, 30 frames per second (FPS), and a bitrate of 3000 kbps, providing sufficient visual clarity for both sprite classification and text recognition.

The collected gameplay featured a wide range of battle scenarios, moves, and Pokémon species. Of the 62 Pokémon species used to train the classification model, 31 appeared in the recorded matches, offering a representative and realistic subset for in-situ system evaluation.

Text Extraction and Validation

The system uses Tesseract OCR, version 5.3.3.20231005, with default settings, to extract a wide range of textual information from gameplay frames. This information includes Pokémon levels, move names, Pokémon nameplates during battle, and on-screen timers.

Depending on the current battle state, specific regions of interest are cropped from each frame and fed into Tesseract. For example:

- level information displayed under each Pokémon during Team Preview (e.g., “Lv. 50”)

- battle messages indicating move usage or effects (e.g., “Flutter Mane used Shadow Ball!”)

- in-battle name tags and remaining time indicators

To ensure the extracted information is valid, the system cross-references Tesseract’s output with a structured reference database. This database contains lists of all valid Pokémon names and legally allowed move names, enabling the system to discard incorrect or misread entries.

We constructed the database using data extracted from PokéAPI (Hallett et al., 2024), with manual curation to remove duplicates and inconsistencies. The database is hosted on Microsoft Azure and queried in real time during execution. Its relational structure ensures that each move is associated only with Pokémon that can legally learn it, enhancing the precision of battle data (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

Relational Schema of the Pokémon Name and Move Validation Database

JSON-Based Battle Notation System

Within the field of Pokémon gameplay analysis, a standardised method for representing and processing battle events in structured form has not yet been established. While platforms such as Pokémon Showdown offer replay systems that store battle data, these formats are tailored to their specific environments and are not generalised for broader AI or analytical applications (Luo, 2024). Similarly, existing research efforts often define custom representations that address only narrow experimental needs (Norström, 2019; The Pokémon Company, 2024d).

To enable consistent, machine-readable analysis across diverse gameplay recordings, our system defines a custom JSON-based notation for Double Battles. This notation, originally described by Lladó Herrera (2024), captures both static elements (e.g., teams, levels) and dynamic sequences (e.g., actions, switches, outcomes). The following section outlines the JSON schema implemented by the system:

Root Structure

- player1: information about the first player

- player2: information about the second player

- battle_log: list of objects representing the sequence of turns in the battle

- winner: name of the winning player

Player Object

Each player object (player1 and player2) contains:

- name: player’s name

- team: list of Pokémon objects representing the player’s team

Pokémon Object in Team

Each Pokémon object within a team contains:

- name: Pokémon’s name

- level: Pokémon’s level (e.g., “Lv. 50”)

Battle Log Object

Each object in the battle_log list represents a turn in the battle and contains:

- turn: turn number

- player1_active: list of objects representing the active Pokémon for player 1 during this turn

- player2_active: list of objects representing the active Pokémon for player 2 during this turn

- actions: list of objects representing the actions taken by a player during the turn

Active Pokémon Object

Each object in the player1_active and player2_active lists represents the Pokémon currently on the battlefield at the beginning of the turn. Each player can have up to two active Pokémon in these lists. The fields include:

- name: active Pokémon’s name, or null if no Pokémon is present in that slot

Action Object

Each object in the actions list represents an action performed during the turn and contains:

- player: player performing the action (“player1” or “player2”)

- move: move used during the action; if the move is labelled as “Switch”, it indicates a substitution in which a Pokémon is being swapped out for another Pokémon on the team

- source: Pokémon performing the move

- target: object representing the Pokémon entering the battlefield during a substitution

This field is populated only when the move is “Switch”; otherwise, it remains null. When a substitution occurs, the target object contains:

- player: player whose Pokémon is being switched in

- pokemon: name of the Pokémon being switched into the battlefield

System Architecture and Workflow

The system integrates three core components: a YOLOv8m image classification model for Pokémon recognition during Team Preview, a Tesseract OCR-based module for extracting text information during gameplay, and a validation database hosted on Azure to ensure the correctness of recognised Pokémon names and moves. These components are coordinated by a state machine architecture, which governs the execution flow according to the battle phase.

Class Design

The system is implemented using an object-oriented structure. Its core logic is encapsulated in the BattleState class, which stores the entire match, including Player instances, the battle log, and the final outcome. Each Player holds a team of Pokémon, while each turn is represented by a BattleLog object, which includes active Pokémon and a list of Action instances. The relationships between these data structures are illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5

UML Class Diagram Showing the Relationships Among the Main Data Structures Used in the System

This design provides modularity and clear data separation between phases, enabling easier updates and extensibility for future features, such as ability tracking or item usage.

State-Based Workflow

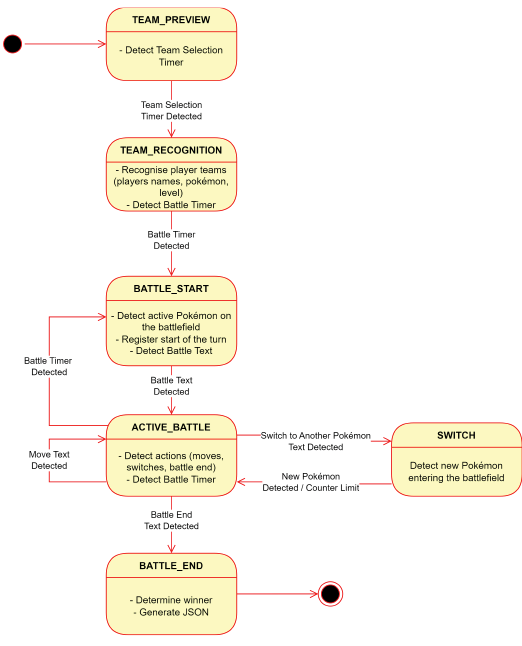

The system operates as a state machine, transitioning between predefined stages based on visual cues extracted from battle footage. This architecture ensures that relevant components—classification, OCR, or logging—are activated only during the appropriate phase of the match, improving both accuracy and efficiency. An overview of this process is illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6

General State Machine Workflow for Pokémon Battle Visual Recognition System

Video was sampled at two frames per second (one frame every fifteen from the native 30 FPS). This rate was selected to significantly reduce computational load and storage requirements while maintaining sufficient temporal resolution to capture all relevant gameplay transitions, including move executions and Pokémon switches. Preliminary tests showed that higher sampling rates produced redundant frames without improving recognition accuracy, confirming that 2 FPS provided an optimal trade-off between efficiency and reliability.

The key states in the workflow are described below:

- TEAM_PREVIEW: Processing begins when the system identifies the “01:29” timer positioned at the upper centre of the screen. Detection of this element designates the start of Team Preview and advances the workflow to the next state.

- TEAM_RECOGNITION: This state is triggered when “Stand By” messages appear for both players. The system:

- extracts player names using OCR

- detects twelve Pokémon sprites (six per player) using the YOLOv8m classifier

- captures level text (e.g., “Lv. 50”) using OCR from designated regions

- BATTLE_START: Triggered when Pokémon appear on the battlefield. The system reads four text areas where names are displayed using Tesseract OCR. Valid names are confirmed against the Azure database, while unrecognised names remain null until identified in later frames. The state ends when text indicating action selection is detected.

- ACTIVE_BATTLE: Once the battle begins, the system monitors a mid-screen region for gameplay messages. It applies four OCR configurations (two-page segmentation modes with and without median blur) to maximise text capture. During this phase, the system:

- logs move using patterns like “used [Move]”

- recognises switches (e.g., “come back!”, “withdrew”)

- detects end-of-battle messages (e.g., “You defeated”, “You lost”)

Redundant actions are filtered to avoid duplicates. A new turn begins when the timer is detected again, shifting the state back to BATTLE_START.

- SWITCH: Activated when a switch is detected in the previous state. Pokémon sent out are identified through phrases like “Go! [Pokémon]” or “[Player] sent out [Pokémon]!”, depending on the side. Names are validated against the database. If no valid name is detected within 200 frames, the system times out and returns to the ACTIVE_BATTLE state.

- BATTLE_END: When final messages appear, the system checks for the terms “WON!” or “LOST” at the lower left of the screen to determine the winner. This outcome is logged, and the final JSON file is generated, marking the end of processing.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

System Configuration

The analysis was conducted using an ASUS Zenbook UM425UA (ASUSTeK Computer, n.d.), featuring an AMD Ryzen 5700U processor, 16 GB of RAM, and a 512 GB SSD. System execution was performed locally on this laptop environment. The analysis was conducted using an ASUS Zenbook UM425UA (ASUSTeK Computer, n.d.), featuring an AMD Ryzen 5700U processor, 16GB of RAM, and a 512GB SSD. System execution was carried out locally on this laptop environment.

The evaluation set consisted of eight recorded matches in 1080p at 30 FPS with a bitrate of 3000 kbps. Processing efficiency was achieved by selecting a frame interval of 15, corresponding to two analysed frames per second. The evaluation set consisted of eight recorded matches in 1080p at 30 fps with a bitrate of 3000 kbps. Processing efficiency was achieved by selecting a frame interval of 15, equating to two analysed frames per second.

Testing Methodology

This section outlines the validation procedures applied to both the YOLO classification model and the complete Pokémon battle analysis system. The evaluation results should be interpreted within an exploratory framework, as the primary objective was to test the system’s accuracy and robustness under controlled gameplay conditions rather than to generalise findings across all competitive scenarios. Two levels of evaluation were conducted: offline model testing and end-to-end system validation using gameplay recordings.

The YOLO model was tested using a synthetic dataset generated through data augmentation, as described in Section 3.1. Due to the limited availability of original sprites—only one per Pokémon—this approach allowed the creation of varied, labelled data suitable for assessing classification accuracy under controlled conditions.

In parallel, the full system was evaluated using eight recorded Pokémon battles, simulating real-world usage scenarios. The system’s output, stored in JSON format, was compared against manually labelled ground truth extracted from the videos. These comparisons were used to verify the accuracy of sprite recognition, move extraction, active Pokémon tracking, and battle outcome detection.

Together, these tests assessed both the individual components and overall reliability of the system when applied to practical gameplay footage.

YOLO Model Testing Results

The YOLO v8m classifier was evaluated on the augmented Pokémon sprite dataset to assess its baseline classification capability before gameplay testing. As previously detailed in Lladó Herrera (2024), the model achieved perfect performance across all metrics, obtaining mean precision, recall, and F1-scores of 1.00 on every evaluated class. This indicates that the network successfully learned the sprite features introduced through augmentation—such as rotation, blur, and colour variation—without any class imbalance or misclassification.

While these metrics confirm excellent classification performance within the controlled dataset, they also reflect the limited scope of this baseline experiment. Although the training and validation sets were independent and contained no overlapping sprites, both were derived from the same source collection prior to augmentation. Consequently, the perfect results likely reflect the model’s ability to memorise augmented visual patterns rather than its performance on entirely unseen data. This evaluation was conducted solely to verify the stability of the classification pipeline and its feature extraction process under ideal conditions. Future research could address stricter dataset independence through pre-split augmentation and the incorporation of an external validation set.

These results confirm the model’s robustness for static sprite recognition under controlled conditions. However, such performance reflects the simplified nature of the dataset rather than the complexity of real gameplay. Therefore, the subsequent validation stage using battle footage was conducted to examine model reliability under dynamic conditions involving motion blur, overlapping entities, and changing visual contexts.

Full System Validation

This section presents the validation results of the Pokémon battle analysis system, with tables summarising the accuracy and performance of its individual components.

Table 1 summarises the main characteristics of the gameplay recordings used for system validation, including video duration, processing time, and number of turns. This information highlights both the diversity of the dataset and the computational workload associated with each match.

Table 1

Characteristics of the Recorded Gameplay Videos

|

Battle video |

Video length |

Number of turns |

Process time |

|

1 |

13:08 |

9 |

53:45 |

|

2 |

09:51 |

6 |

36:16 |

|

3 |

06:24 |

4 |

23:51 |

|

4 |

09:41 |

7 |

40:34 |

|

5 |

09:07 |

5 |

35:25 |

|

6 |

10:09 |

7 |

37:31 |

|

7 |

12:01 |

8 |

46:38 |

|

8 |

15:17 |

11 |

69:23 |

Note. Adapted from Lladó Herrera, M. R. (2024). Computer Vision in Gaming: Analysing Pokémon Battles [Unpublished master’s dissertation]. The University of Manchester.

Team Preview Validation

The evaluation of the Team Preview stage considered three primary tasks—player name extraction, sprite identification, and level recognition—as measures of system accuracy.

Player names were correctly identified in 15 out of 16 cases across the eight gameplay videos, yielding an average accuracy of 93.75 %. The single error was recorded in video 4, where only one of the two names was accurately recognised.

For Pokémon sprite recognition, the system correctly identified an average of 11.63 out of 12 sprites per video, yielding an overall accuracy of 96.88 %. In five videos, all sprites were correctly recognised, whereas the remaining three each contained a single misclassification, demonstrating consistent detection performance within the evaluated dataset. However, the model showed reduced accuracy for specific Pokémon, such as Miraidon and Ursaluna-Bloodmoon, highlighting the difficulty of recognising certain species and identifying areas for further optimisation in future iterations.

The Pokémon level detection task demonstrated the highest reliability, achieving an average accuracy of 98.96 %. In seven of the eight videos, all level indicators were accurately captured, with a single error occurring in video 4.

Battle Validation

This section presents the system’s performance during the battle phase, including the validation of active Pokémon tracking, action recognition, and winner detection.

Active Pokémon tracking was measured by assessing the system’s ability to correctly identify the four positions on the battlefield during each turn—two for each player. The system was designed to recognise whether each position was occupied by a valid Pokémon name or intentionally left empty (null). Across all eight videos, a total of 228 positions were evaluated. The system achieved an average accuracy of 99.22 %, with six of the eight videos attaining 100% accuracy. Single misidentifications occurred in videos 3 and 5, each slightly reducing the respective video’s score.

Action validation was divided into two stages. The first focused on confirming that each action was correctly attributed to the appropriate player and that the corresponding move was accurately extracted. Out of a total of 185 total actions, the system achieved an average accuracy of 96.22 % for both player and move detection. Most videos achieved full accuracy, with minor declines observed in videos 1, 5, 7, and especially video 8, which recorded the highest number of incorrect recognitions.

The second stage evaluated the system’s ability to identify the source Pokémon (the one executing the move) and, in the case of switch actions, the target Pokémon (the one entering the battlefield). Across the same set of 185 actions, source identification achieved an average accuracy of 96.22 %. Target identification, applicable only to switch events, was evaluated across 18 relevant cases and achieved an average accuracy of 91.67 %, with perfect accuracy observed in five of the eight videos. Accuracy dropped notably in video 7 to 50 %, due to one incorrect recognition out of two attempts.

Finally, winner detection was evaluated by comparing the system’s reported outcome with the actual result of each battle. The system correctly identified the winner in seven of the eight videos, achieving an overall accuracy of 87.50 %. The only failure occurred in video 5, where the system did not detect the end of the battle and, consequently, could not assign a winner.

Summary of Results

Table 2 provides an overview of the consolidated performance metrics for each evaluated stage.

Table 2

Summary of System Validation Performance

|

Phase |

Validation task |

Accuracy (%) |

Evaluation basis |

|

Team |

Player name recognition |

93.75 |

2 names per match |

|

Pokémon sprite recognition |

96.88 |

12 sprites per match |

|

|

Pokémon level recognition |

98.96 |

12 level tags per match |

|

|

Battle |

Active Pokémon recognition |

99.22 |

228 positions total |

|

Action recognition |

96.22 |

185 actions total |

|

|

Source Pokémon recognition |

96.22 |

185 actions total |

|

|

Target Pokémon recognition |

91.67 |

18 switch events |

|

|

Winner recognition |

87.50 |

8 matches |

Note. Adapted from Lladó Herrera, M. R. (2024). Computer Vision in Gaming: Analysing Pokémon Battles [Unpublished master’s dissertation]. The University of Manchester.

Discussion

The results show that a vision-based pipeline can reliably extract structured information from native Pokémon Double Battle footage. In the controlled sprite dataset, the YOLOv8m classifier achieved perfect precision, recall, and F1. In real gameplay, accuracy remained high for tasks tied to stable HUD regions: team-preview sprite identification (96.88 %), player-name recognition (93.75 %), and level recognition (98.96 %). This is consistent with guidance in the Tesseract documentation, which indicates that OCR performs best on clean, high-contrast interface text at adequate resolution (Tesseract OCR, n.d.-a). During battle, the state-based design supported robust active-Pokémon tracking (99.22 %) and action recognition (96.22 %). The most challenging component was target identification during switch events (91.67 %), where rapid scene changes and transient overlays increase contextual ambiguity for text extraction. Class-specific variability observed in Team Preview (e.g., lower rates for certain species) indicates opportunities for targeted augmentation or post-processing to improve robustness in visually similar cases.

Relative to prior work—where most Pokémon AI research has relied on structured inputs such as simulators or battle logs (Hu et al., 2024; Norström, 2019; Simoes et al., 2020)—this study operates directly on native broadcast-style video and demonstrates that comparable reliability can be obtained in stable interface states. At the same time, the drop in accuracy for fast transitions and occluded elements underscores the importance of segmenting gameplay into states before applying computer-vision modules and suggests that further refinements should prioritise these dynamic segments.

Consistent with the paper’s exploratory scope, these findings are intended to demonstrate technical feasibility rather than statistical generalisation. The combined use of a YOLO-based image classifier for sprite recognition and Tesseract OCR for textual elements provides a practical basis for automated, minimally supervised data extraction from Double Battles, enabling downstream analytics and tooling for competitive contexts.

FUTURE WORK AND CONCLUSIONS

Future Work

Several avenues exist for expanding and refining the current system:

- Dataset Expansion and Event Coverage. The current system was trained on a curated dataset comprising the most frequently used competitive Pokémon. Expanding this dataset to include the full in-game roster could enhance the model’s generalisability. Furthermore, the system could be extended to recognise more complex gameplay events, such as move direction or inferred targeting. Enhancing event detection would increase the richness of the generated data and strengthen the analytical value of the JSON notation system.

- Real-Time System Integration. The current system operates on pre-recorded gameplay, making it well suited for post-match analysis. However, adapting it for real-time use could enable dynamic applications such as live coaching, tactical support, or spectator-oriented tools. Achieving this would require improvements in frame processing and inference time to ensure system responsiveness. Real-time integration could also support automated match commentary systems, offering context-aware narration during live events.

- Training AI Agents Using Real Game Data. Existing research in Pokémon AI has largely relied on simulated data from platforms like Pokémon Showdown (Norström, 2019; Simoes et al., 2020). In contrast, the structured outputs produced by the present system provide a pathway for training AI agents using actual gameplay footage. This approach introduces greater variability and more accurately reflects in-game dynamics, although it necessitates addressing potential challenges, such as visual overlays or screen artefacts in streamed content.

Conclusions

This research introduces a computer vision–based system for analysing Pokémon Double Battles. Gameplay video was transformed into structured representations, providing a clear link between visual elements and usable analytical data. Experimental results indicated reliable performance in player name recognition, sprite classification, and level detection, confirming the system’s capability to interpret game information accurately and support applications in strategy evaluation and post-match review.

Beyond its immediate performance, the system contributes a broader foundation for structured game analysis. The development of a custom dataset and a JSON-based notation framework enable detailed tracking and documentation of gameplay events, offering tools for both strategic post-game review and future applications in AI-driven analysis. While overall performance remained strong across various validation stages, certain challenges were identified. These included occasional misrecognitions or interface inconsistencies that impacted isolated predictions. These outcomes emphasise the importance of continued refinement to increase the adaptability of the approach to a broader range of gameplay contexts.

Ultimately, the project not only met its original technical goals but also lays the groundwork for further advancements in the application of computer vision and AI within interactive gaming environments.

DISCLAIMER

The images used in this paper are property of Nintendo, Game Freak, and Creatures Inc. They are included solely for academic and analytical purposes under the permitted use exceptions established in Legislative Decree No. 822 (Peruvian Copyright Law).

REFERENCES

ASUSTeK Computer. (n.d.). Zenbook 14 (UM425UA). Retrieved August 27, 2024, from https://www.asus.com/laptops/for-home/zenbook/zenbook-14-um425-ua/

Bazan, D., Casanova, R., & Ugarte, W. (2024). Use of custom videogame dataset and YOLO model for accurate handgun detection in real-time video security applications [Manuscript in preparation]. Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas.

Cheng, Y. (2023). Character detection in first person shooter game scenes using YOLO-v5 and YOLO-v7 networks. In 2023 2nd International Conference on Data Analytics, Computing and Artificial Intelligence (ICDACAI) (pp. 825-831). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/icdacai59742.2023.00160

El-Nasr, M. S., Drachen, A., & Canossa, A. (2016). Game analytics. Springer.

Elgato. (2024). 4K X. Retrieved August 19, 2024, from https://www.elgato.com/uk/en/p/game-capture-4k-x

Hallett, P., Adickes, Z., Marttinen, C., Vohra, S., & Pezzè, A. (2024). PokéAPI. Retrieved August 25, 2024, from https://github.com/PokeAPI/pokeapi

HEROZ, I. (2024, February 9). HEROZ、将棋AIの技術を生かし、ポケモンバトルに特化したゲーム演出AI 「Pokémon Battle Scope」を株式会社ポケモンと共同開発 「ポケモン竜王戦2024」ゲーム部門の配信画面に初導入 [HEROZ, leveraging its Shogi AI technology, has jointly developed with The Pokémon Company a game presentation AI specialized for Pokémon battles called ‘Pokémon Battle Scope,’ which is being introduced for the first time on the broadcast screen of the game division at the ‘Pokémon Ryuo Championship 2024]. https://heroz.co.jp/release/2024/02/09_press01-3/

Hu, S., Huang, T., & Liu, L. (2024). PokéLLMon: A human-parity agent for Pokémon battles with large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.01118. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2402.01118

Jocher, G., Chaurasia, A., & Qiu, J. (2024). Ultralytics YOLO (Version 8.2.82) [Software]. Ultralytics. Retrieved from https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics

Lladó Herrera, M. R. (2024). Computer vision in gaming: Analysing Pokémon battles [Unpublished master’s dissertation]. The University of Manchester.

Luo, G. (2024). Pokémon Showdown [Computer software]. Retrieved August 25, 2024, from https://github.com/smogon/Pokemon-Showdown

Moussaoui, H., Akkad, N. E., Benslimane, M., El-Shafai, W., Baihan, A., Hewage, C., & Rathore, R. S. (2024). Enhancing automated vehicle identification by integrating YOLO v8 and OCR techniques for high-precision license plate detection and recognition. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 14389. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65272-1

Norström, L. (2019). Comparison of artificial intelligence algorithms for Pokémon battles [Master’s thesis, Chalmers University of Technology]. Chalmers Open Digital Repository. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12380/300015

OBS Project. (2024). OBS Studio. Retrieved August 19, 2024, from https://obsproject.com/

Pokémon Database. (2024). Pokémon sprite archive [Database]. Retrieved August 24, 2024, from https://pokemondb.net/sprites

Redmon, J., Divvala, S., Girshick, R., & Farhadi, A. (2016). You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 779-788. https://doi.org/10.1109/cvpr.2016.91

Simoes, D., Reis, S., Lau, N., & Reis, L. P. (2020). Competitive deep reinforcement learning over a Pokémon battling simulator. In 2020 IEEE International Conference on Autonomous Robot Systems and Competitions (ICARSC). IEEE.

Smith, R. (2007). An overview of the Tesseract OCR engine. In Ninth International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition (ICDAR 2007). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICDAR.2007.4376991

Takahiro, H., & Tomohiro, T. (n.d.). Amaze the world by the power of AI. HEROZ, Inc. Retrieved August 13, 2024, from https://heroz.co.jp/en/company/

Tesseract OCR. (n.d.-a). Improving the quality of the output. Retrieved August 16, 2024, from https://tesseract-ocr.github.io/tessdoc/ImproveQuality.html

Tesseract OCR. (n.d.-b). Tesseract User Manual. Retrieved August 16, 2024, from https://tesseract-ocr.github.io/tessdoc/

Thapliyal, T., Bhatt, S., Rawat, V., & Maurya, S. (2023). Automatic license plate recognition (ALPR) using YOLOv5 model and Tesseract OCR engine. In 2023 First International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Electronics and Computational Intelligence (ICAEECI). IEEE.

The Pokémon Company. (2024a). 2024 Pokémon North America International Championships. Retrieved August 24, 2024, from https://www.pokemon.com/us/play-pokemon/internationals/2024/north-america/about

The Pokémon Company. (2024b). Pokémon in figures. Retrieved August 6, 2024, from https://corporate.pokemon.co.jp/en/aboutus/figures/

The Pokémon Company. (2024c). Video game rules, formats, & penalty guidelines. Retrieved August 6, 2024, from https://www.pokemon.com/static-assets/content-assets/cms2/pdf/play-pokemon/rules/play-pokemon-vg-rules-formats-and-penalty-guidelines-en.pdf

The Pokémon Company. (2024d). With AI, now everybody can totally enjoy battle watching. The Pokémon Company. Retrieved August 5, 2024, from https://corporate.pokemon.co.jp/en/topics/detail/118.html

The Pokémon Company International. (2024). About us. The Pokémon Company International. Retrieved August 13, 2024, from https://corporate.pokemon.com/en-us/about/

Ultralytics. (2024). This is Ultralytics. Retrieved August 26, 2024, from https://www.ultralytics.com/about

Yannakakis, G. N., & Togelius, J. (2018). Artificial intelligence and games (Vol. 2). Springer.