SMART CITIES AND PUBLIC SAFETY: EMPIRICAL

EVIDENCE ON VIDEO SURVEILLANCE AND

DEVELOPMENT IN APARECIDA DE GOIÂNIA CITY

MARCOS DIAS DE PAULA

https://orcid.org/0009-0003-1254-9834

Universidade Federal de Goiás, Brazil

PEDRO H. GONÇALVES

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9919-6557

Universidade Federal de Goiás, Brazil

Received: September 5, 2025/ Accepted: October 23, 2025

doi: https://doi.org/10.26439/interfases2025.n022.8258

ABSTRACT. This article analyzes the relationship between the implementation of urban video surveillance, as part of the smart cities strategy, and social and public safety indicators in Aparecida de Goiânia (GO) in Brazil. Using a quantitative approach with ordinary least squares (OLS) regression, this study examines the influence of technology on the reduction of homicides and on the Federation of Industries of the State of Rio de Janeiro (FIRJAN) education, health, employment, and income indexes from 2014 to 2024. The theoretical framework addresses the concepts of smart cities, human development, and urban security, supported by international standards and references, including the works of Amartya Sen and the ISO 37122 guidelines. The results reveal negative correlations between the presence of cameras and violence rates; however, the robustness tests indicate model limitations, highlighting the need for additional variables and further methodological refinement. Overall, the study contributes to the broader debate on the role of technology in sustainable urban development, particularly in contexts characterized by medium socioeconomic complexity.

KEYWORDS: smart cities / video surveillance / public safety / FIRJAN indicators / human development

CIUDADES INTELIGENTES Y SEGURIDAD PÚBLICA: EVIDENCIA

EMPÍRICA SOBRE VIDEOVIGILANCIA Y DESARROLLO EN LA CIUDAD

DE APARECIDA DE GOIÂNIA

RESUMEN. Este artículo analiza la relación entre la implementación de la videovigilancia urbana, como parte de la estrategia de ciudades inteligentes, y los indicadores sociales y de seguridad pública en Aparecida de Goiânia (GO), Brasil. Mediante un enfoque cuantitativo con regresión de mínimos cuadrados ordinarios (MCO), el estudio examina la influencia de la tecnología en la reducción de homicidios y en los índices de educación, salud, empleo e ingresos de la Federación de Industrias del Estado de Río de Janeiro (FIRJAN) durante el período 2014–2024. El marco teórico aborda los conceptos de ciudades inteligentes, desarrollo humano y seguridad urbana, apoyándose en normas y referencias internacionales, incluyendo los aportes de Amartya Sen y las directrices ISO 37122. Los resultados revelan correlaciones negativas entre la presencia de cámaras y las tasas de violencia; sin embargo, las pruebas de robustez indican limitaciones del modelo, lo que resalta la necesidad de incorporar variables adicionales y de un mayor refinamiento metodológico. En conjunto, el estudio contribuye al debate más amplio sobre el papel de la tecnología en el desarrollo urbano sostenible, particularmente en contextos caracterizados por una complejidad socioeconómica media.

PALABRAS CLAVE: ciudades inteligentes / videovigilancia / seguridad pública / indicadores FIRJAN / desarrollo humano

INTRODUCTION

The phenomenon of accelerated urbanization, observed on a global scale in recent decades, presents a complex set of challenges for public management and the quality of life of its citizens. The growth of cities has driven the search for innovative solutions to chronic urban problems, ranging from infrastructure and mobility to public safety and social well-being. In this context, the concept of a Smart City emerges as a promising approach, proposing the integration of technology, especially Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), with urban management to optimize services, improve sustainability, and promote citizen participation (Abreu & Marchiori, 2019; Lazzaretti et al., 2019).

Although the use of technology to enhance urban life is not a novel concept, the conceptualization of the smart city as a social issue and a subject of scholarly inquiry is relatively new and continues to evolve. The term smart began to be used in the 1990s, initially referring to the infrastructures required to support information technology. Over time, however, the concept has evolved to encompass a broader perspective, in which digitalization is not an end in itself but rather a tool to support multiple dimensions of urban life, including governance, economy, environment, and quality of life (Abreu & Marchiori, 2019). Within the context of smart cities, there is an ongoing debate regarding the centrality of technology. Some approaches position technology as a key driver in a top-down framework, whereas others argue that technology should be adapted to the needs of citizens in a bottom-up approach (Dameri, 2013, as cited in Alves, 2019, p. 7).

In Brazil, the discussion on Smart Cities has been gaining ground, in both academia and on government agendas. Initiatives such as the Brazilian Charter for Smart Cities, prepared by the Ministry of Regional Development in collaboration with several societal sectors, represent an effort to establish a national public agenda for digital transformation in Brazilian cities. This Charter seeks to integrate the agendas of urban development and digital transformation, guided by the perspectives of environmental, urban, social, cultural, economic, financial, and digital sustainability. It proposes an expanded conception of the smart city, acknowledging the complexity and distinct characteristics of Brazil’s various territories to reduce socio-spatial inequalities (Brasil. Ministério do Desenvolvimento Regional, 2021).

Despite increasing interest, the concept of smart cities still lacks consensus and a unifying definition in Brazil. National research on the topic is multidomain, encompassing fields such as administration, information systems, engineering, and architecture. There is a conceptual predominance that links ICTs with quality of life, as noted by Lazzaretti et al. (2019). However, the mere application of technology does not guarantee that a city becomes smart. The transformation depends on coordinated action between federal spheres, clear strategies, and overcoming barriers such as lack of technical knowledge, investment difficulties, and resistance to change (Roland, 2019).

The evaluation of the performance and degree of “intelligence” of cities is critical to directing planning and public policies. International tools and standards, such as ISO 37122:2019 and its Brazilian version, ABNT NBR ISO 37122:2020, proposed by the Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas (ABNT, 2020), offer sets of indicators to assess progress towards a smart city. However, it is emphasized that the evaluation should not focus only on the technological aspect but consider multiple perspectives, including sustainability, resilience, quality of life, and social aspects (Abreu & Marchiori, 2019).

Within this framework, the relationship among Smart Cities, Regional Development, and the application of social and security indicators assumes particular relevance. The socioeconomic development of Brazilian cities varies considerably, and these disparities can influence their capacity to implement smart city projects (Jordão, 2016). Synthetic indicators such as the Human Development Index (HDI) have historically been used to measure social conditions, despite criticisms about their universal application and disregard for regional particularities (Guimarães & Jannuzzi, 2005).

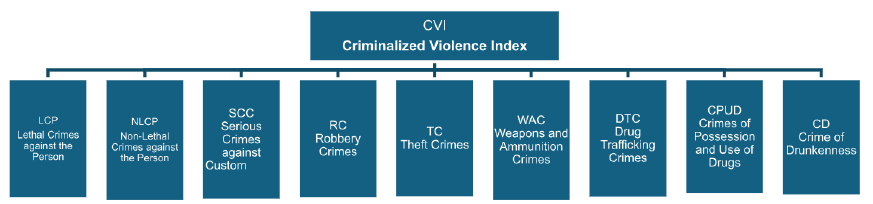

Similarly, violence is a social problem that directly impacts quality of life and development, with different forms of manifestation (Minayo, 2006). Indexes, such as the Criminalized Violence Index (CVI), seek to facilitate the understanding of the factors that influence criminal dynamics and support public policies focused on violence prevention and control. Social cohesion, defined as the level of coexistence between different groups in a city, is also a crucial factor for the urban context (Takiya et al., 2019).

Considering the complexity of the topic and the need to adapt the Smart City concept to the Brazilian context—with its regional particularities and social challenges—this research project aims to examine the interrelation between the implementation of technological initiatives and the performance of social and security indicators. Specifically, this study focuses on the city of Aparecida de Goiânia, which is currently implementing a Smart City project. The initiative encompasses several sectors, including public security, and the municipality has invested in technologies such as video surveillance systems. The relevance of security and human development indicators for the consolidation of Smart Cities in the Brazilian regional context still requires deeper exploration.

Within this context, this dissertation project aims to analyze the relationship between the implementation of information and communication technologies—such as video surveillance—within a Smart City initiative and the potential changes in security indicators (homicides) and quality-of-life indicators (education, health, employment, and income) in a medium-sized Brazilian city. To this end, it seeks to answer the following research questions: How did the implementation of video surveillance in Aparecida de Goiânia alter the Homicide rates and the Federation of Industries of the State of Rio de Janeiro (FIRJAN) indexes for education, health, employment, and income? The study is justified by the need to deepen the understanding of how Smart City initiatives directly contribute to citizens’ well-being and to urban development, taking into account the specificities of the Brazilian context and the importance of multidimensional indicators that extend beyond mere technological application.

RELATED WORK

The study of the relationship between the implementation of video surveillance technologies in the context of smart cities and performance in public safety and social development has been gaining relevance in the Brazilian academic and governmental scenario. This section aims to position the current article—which investigates this relationship in Aparecida de Goiânia (GO) using a quantitative approach—in comparison with other prominent works focused on Brazilian cities, such as Foz do Iguaçu (Chichoski & Marquardt, 2023), Recife (Ferreira et al., 2023), and Manaus (Filho et al., 2024).

Similarities and Conceptual Alignment

The analyzed articles significantly show strong convergence in their emphasis on video surveillance as a central instrument for public safety and contemporary urban management in Brazil.

Video Surveillance as a Smart City Tool

All studies characterize video monitoring as a technological innovation applied to public safety and aligned with smart-city principles. Across the examined cities, the primary objective is to employ this technology for crime prevention and intervention. In Manaus, for instance, the Smart Siege (Cerco Inteligente) system was implemented to enhance police response efficiency and effectiveness, thereby strengthening crime-fighting efforts.

Emphasis on Integration and Governance

There is a consensus on the need for integration and cooperation between public security agencies and municipal administration for the system’s effectiveness.

- In the main article, the Aparecida de Goiânia initiative is part of a broader Smart City project focused on data-driven governance.

- In Foz do Iguaçu, the system’s effectiveness is linked to the structure of the Integrated Municipal Management Cabinet (GGIM), which brings together 21 institutions for dialogue and deliberation.

- In Recife, the system is managed by the Integrated Social Defense Operations Center (CIODS), where the coordination between agencies such as the police and the fire department is considered favorable to advancing the Smart City concept.

- In Manaus, the system is under the responsibility of the Integrated Security Operations Center (CIOPS) and the Integrated Command and Control Center (CICC), which coordinate and integrate state security forces (military police, civil police, and military fire department).

Social Benefit and Sense of Security

The studies agree that video monitoring provides socioeconomic gains and, crucially, increases the sense of security in the population and public road users. In addition to combating crime, video monitoring functions as a social support mechanism, assisting in social defense activities such as managing traffic accidents, monitoring areas of drug use, and even enabling the rescue of individuals during suicide attempts, as reported in the Manaus case.

Institutional and Resource Challenges

All Brazilian contexts face barriers to the full implementation of the system. Works from Foz do Iguaçu (Chichoski & Marquardt, 2023) and Recife (Ferreira et al., 2023) report challenges related to insufficient staffing to operate the platforms—such as the overload of approximately 50 cameras per operator in Foz do Iguaçu—and limited government support for sustained investments and the acquisition of high-value equipment, respectively.

Methodological and Focal Differences

The article on Aparecida de Goiânia differs markedly from the others in its methodological approach, as it is one of the few that attempts to quantify the impact of technology on multidimensional development indicators (Table 1).

Table 1

Comparative Synthesis of Approaches

|

Characteristic |

Article (Aparecida de Goiânia) |

Chichoski y Marquardt (Foz do Iguaçu) |

Ferreira, Novaes y Macedo (Recfe) |

Filho, Santos y Lima (Manaus) |

|

Main |

Quantitative (OLS Regression) |

Qualitative/Descriptive/Exploratory (Empirical/bibliographical research) |

Qualitative (Case study, interviews) |

Qualitative/Exploratory (SSP-AM Data, bibliographical) |

|

Impact Focus |

Statistical correlation between cameras and multidimensional Human Development indicators (IFDM: Education, Health, Employment/ Income) and Homicides |

Operational contribution and border surveillance |

Innovation in the public sector and analysis of innovation classification (incremental/technological) |

Advantages and disadvantages of the “Smart Siege” system and use of images in investigations |

|

Critical Result |

Found negative correlations (cameras vs. violence), but the OLS model showed statistical limitations (heteroscedasticity, specification problems) |

Highlighted the need to improve integration and investment in human resources/maintenance costs |

Insufficient government support and technological deficit (lack of AI/facial recognition) |

Concerns about privacy and the risk of falling into the “myths of the video image” (Silbey, 2004) |

|

Technological Scale |

Large scale infrastructure (3,275 cameras installed, 720 km of fiber optics) |

Smaller scale (288 cameras in total, migrating from radio to 240 km of fiber optics) |

Existing system with technological deficit, but with expansion plan for 2,000+ cameras and addition of AI analytics |

Medium scale (more than 500 cameras) |

THEORETICAL FOUNDATION

The concept of Smart Cities emerged in response to contemporary urban challenges, proposing the strategic use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) to improve public services, promote sustainability, social inclusion, and foster regional development. The Brazilian Charter for Smart Cities reinforces this vision by highlighting that a smart city is not limited to the adoption of technologies, but rather to their use as a means of improving quality of life, promoting social justice, and reducing inequalities.

In this sense, the approach adopted by Covas and Covas (2020) shows that the smartification of territories is directly linked to the ability to mobilize collective intelligence, integrating economic, social, environmental, and cultural dimensions. Technology, therefore, acts as a catalyst; however, its effectiveness depends on the articulation between public and private actors and the civil society, which positions technology as a means to achieve objectives and not as a central element, reinforcing the more humanistic and integrative aspect of the proposal for implementing smart cities.

Sancino and Lorraine (2020) complement this perspective by arguing that leadership is a crucial element in smart city governance, fundamental for aligning technological objectives with social interests and local specificities. The absence of collaborative governance and solid public policies can constrain the benefits of digital transformation, particularly in developing countries.

The measurement of a city’s degree of intelligence is a methodological challenge widely discussed in the literature. The international standard ABNT NBR ISO 37122:2020 establishes a set of indicators that enables the evaluation of the smart city performance, covering aspects such as economy, education, environment, security, mobility, and governance. However, Abreu and Marchiori (2023) point out that, although the standard is an important reference, it has limitations, such as the absence of specific indicators for data privacy and digital security, as well as a fragmentation among the topics of sustainability, intelligence, and resilience.

In the Latin American context, Gomes et al. (2016) propose a specific index that incorporates the region’s socioeconomic and structural particularities and integrates the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) across the dimensions of economy, environment, governance, infrastructure, and social aspects. This approach aims to address the limitations of applying global models to the realities of Latin American and Caribbean countries.

The relationship of smart cities, public safety, and human development is central to the debate on sustainable urban development. Jordão (2016) argues that, beyond digitalization, smart city initiatives must be aligned with local social needs, prioritizing inclusion, social cohesion, and the reduction of inequalities. This perspective expands the traditional understanding of smart cities by emphasizing their social and human-centered dimensions.

The Human Development Index (HDI) has been widely used as a metric for assessing social well-being in cities, although it presents methodological limitations, as pointed out by Guimarães and Jannuzzi (2005). These authors emphasize that, although the HDI is a relevant indicator, it can mask internal inequalities, making it necessary to complement it with other specific metrics, such as the CVI developed by Lira (2013), which provides a territorialized analysis of crime and serves as a robust tool for supporting public security policies.

From an economic perspective, the concept of development has historically been linked to the notion of social well-being and, for a long period, was interpreted as synonymous with economic growth, especially in its regulatory aspects. However, with the advancement of theoretical reflections and the emergence of multidimensional approaches, this conception was gradually reformulated, incorporating variables that extend beyond the limits of wealth generation and focus, above all, on the elements that directly shape the population’s quality of life.

At the end of the 20th century, this discussion was significantly enriched by the studies of economist Amartya Sen, whose theoretical contribution repositioned development as a process centered on expanding the real freedoms that individuals are able to exercise. For Sen (2000), development must be understood beyond an exclusively economic perspective, incorporating elements related to human capabilities and quality of life. This implies considering, in an integrated manner, both the individual and collective dimensions of well-being.

Sen’s central critique lies in the observation that the mere generation of wealth is not, in itself, a sufficient to promote social well-being. This outcome depends, above all, on people’s agency and their substantive freedoms—that is, the effective capacity to make choices and pursue valued life goals within contexts where the necessary means are available.

In this regard, Sen’s conception of development laid the foundation for the creation of new instruments to evaluate quality of life, among which the Human Development Index (HDI) stands out. This indicator incorporated fundamental dimensions such as health, education, and income, providing an alternative and more comprehensive metric for the comparative analysis of development across countries and regions.

In the Brazilian context, Sen’s theoretical proposal inspired the formulation of the Firjan Municipal Development Index (IFDM), created by FIRJAN. Although it is based on categories similar to those of the HDI—income, health, and education—the IFDM differs methodologically in the variables considered and the weights assigned in constructing the index, reflecting a contextualized application of the human development approach at the local level.

The city of Manaus, for example, adopted video surveillance systems as part of its smart city strategy, aiming to reduce crime rates and increase the perception of security. However, studies such as that of Filho et al. (2024) indicate that, while video surveillance can positively impact crime prevention and the investigation of offenses, it also raises concerns regarding privacy, the ethical use of data, and the potential to reinforce inequalities, particularly in the absence of well-structured digital governance.

The use of data is a fundamental component in the management of smart cities. However, Rezende et al. (2019) warn that there is a fine line between making data accessible to enhance public services and infringing on citizens’ privacy. The General Data Protection Law (LGPD) in Brazil and the Access to Information Law (LAI) are legal frameworks that must be adhered to in the implementation of smart city projects. Additionally, Paes et al. (2021) argue that data governance should be centered on sustainable urban metabolism models, in which the collection, analysis, and use of data serve not only to enhance operational efficiency but also to promote social and environmental sustainability.

Brazilian experiences in developing smart cities reveal a range of challenges, including the lack of integration among public policies, insufficient technological infrastructure in many regions, and low maturity in the data culture. Furthermore, Martinelli et al. (2020) indicate that, although the benefits of smart cities are positively perceived, many initiatives still lack strategic planning, particularly with regard to social inclusion and meaningful citizen participation.

In the specific case of the city of Aparecida de Goiânia, the focus of this study, initiatives such as the implementation of the video surveillance system are part of a broader digital transformation effort known as the Smart City Project. The municipality of Aparecida de Goiânia has gained national prominence through the implementation of a comprehensive smart city project, which integrates advanced technological infrastructure, data-driven governance, and public security strategies grounded in urban intelligence. The project represents a convergence of technological innovation, regional development, and the promotion of security, aligning with the guidelines of the Brazilian Charter for Smart Cities and the recommendations of ABNT NBR ISO 37122.

The city of Aparecida de Goiânia took a major step towards consolidating its smart city model with the inauguration of the Center for Technological Intelligence (CIT). According to the City Hall, the CIT will serve as the “brain” of the city, receiving real-time information from approximately 700 cameras initially installed at strategic locations, including streets, squares, schools, health units, and public offices. The objective is to enhance the city’s urban monitoring capacity by integrating data on security, mobility, infrastructure, and public services, thereby optimizing decision-making and incident prevention in accordance with the principles of digital governance and data-driven management.

To support this operation, an extensive infrastructure of 720 km of fiber-optic cables was installed, covering the city’s entire urban territory. This high-capacity network ensures the interconnectivity of public systems, enabling high-speed data transmission with low latency—an essential requirement for the operation of critical services such as security, mobility, and integrated urban management. Additionally, the municipality established its own data center, with a storage capacity of 4,600 TB. This infrastructure supports video surveillance operations and the analysis of large volumes of data from multiple areas of public administration, enhancing the analytical and predictive capabilities of municipal management.

The system became operational in 2024 with 3,275 cameras to assist security forces in combating crime and supporting other public services. Of these, 1,632 cameras were installed in schools, 1,140 in health units, and 503 dedicated to urban monitoring. The installed cameras are high-resolution, with a range of up to 2,000 meters, and are monitored in real time by the Center for Technological Intelligence. The project resulted from research conducted at the Laboratory for Research, Development, and Innovation in Interactive Media at the Federal University of Goiás.

Based on the information presented, it is evident that the implementation of the Smart City Project of Aparecida de Goiânia (GO) has enabled significant improvements in the municipality’s urban infrastructure. However, it is necessary to assess whether these initiatives have effectively influenced indicators such as the HDI and CVI, and whether such changes have made a significant contribution to consolidating the concept of a smart city within the regional context.

Understanding regional development, especially in peripheral or medium-sized urban contexts such as Aparecida de Goiânia, requires an approach that goes beyond explanations based solely on geographical factors or the accumulation of physical capital. Contemporary theories of regional development incorporate elements such as innovation, technology diffusion, institutional capabilities, and territorial cooperation networks. Within this framework, the neo-Schumpeterian approach assumes a central role, considering that regional development is intrinsically linked to the ability to generate, adapt, and diffuse innovations at a local scale, emphasizing the evolutionary dynamics of territories.

By shifting the focus from physical capital to technological, cognitive, and institutional capital, neo-Schumpeterian theorists assign particular importance to the role of the State and public innovation policies as drivers of regional transformation. The smart city, as an urban management strategy based on digital technologies and integrated information systems, represents a materialization of these ideas, embedding innovation as a fundamental component. As examined in this work, the implementation of urban video surveillance systems not only expands the State’s capacity to respond to crime but also generates positive externalities related to security, public trust, investment attraction, and improvements in quality-of-life indicators.

The articulation between the smart city project and social indicators underscores the relevance of the neo-Schumpeterian approach, emphasizing that regional development results from specific trajectories of learning, institutional capacity, and social and technological innovation. From this perspective, video surveillance should not be regarded merely as a technical artifact but as part of a broader process of institutional modernization and the development of endogenous capabilities. This aligns with the concept of regional innovation systems, in which the territory functions as an active space for knowledge production and for the coordination of public, private, and social actors, capable of fostering development based on context-specific and sustainable solutions.

The reviewed literature shows that the concept of Smart Cities goes beyond the simple adoption of technologies. It is a complex process that requires collaborative governance, the development of indicators that reflect local realities, data protection, and a focus on human development and public safety. The intersection between technology, social development, and urban security is, therefore, central to the consolidation of smart cities in Brazil, especially in regional contexts like that of Aparecida de Goiânia.

METHODOLOGY

This research project adopts a quantitative, qualitative, and exploratory methodological approach, based on a case study of the implementation of video surveillance in the city of Aparecida de Goiânia.

The research considers crime hotspots from 2014 to 2024, as well as quantitative data, with a temporal division between the periods before (2014–2017) and after (2018–2024) the implementation of video surveillance in the city of Aparecida de Goiânia, GO. The crimes comprising the CVI proposed by Lira (2013), presented at the 2nd Consad Congress on Public Management, will be considered in this study. From a quantitative point of view, the data analysis will proceed with the use of descriptive statistics, followed by multivariate statistical analysis using the OLS method, with the estimation of models, analysis of results, and analysis of residuals.

In seeking to establish the methodological relevance of this research, it was found that studies examining potential relationships between socioeconomic indicators and crime are relatively common. Authors such as Silva et al. (2017) and Oliveira (2018) serve as examples. However, studies that intend to represent the phenomenon from a multivariate perspective are still rare. On the other hand, multivariate statistical methods have proven efficient in many criminological explanations.

The composition of CVI, as shown in Figure 1, comprises nine categories of crimes, with the combination of indicators formed by a set of criminal variables. According to Lira (2013), by correlating these variables with socioeconomic information, the CVI aims to facilitate the understanding of the structural factors that likely influence criminal dynamics, as well as to support the development of public policies and strategies for the prevention, control, and mitigation of violence.

Figure 1

CVI

Note. Adapted from Índice de Violência Criminalizada (IVC) [Criminalized Violence Index (CVI)], by P. Lira, 2013, in II Congresso Consad de Gestão Pública – Painel 62: Gestão em segurança pública, Vitória (https://consad.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/%C3%8DNDICE-DE-VIOL%C3%8ANCIA-CRIMINALIZADA-IVC3.pdf).

Based on the characteristics of the indicators presented above, it can be argued that they represent typologies directly reflecting the essential conditions related to societal security and can be considered for evaluation within the scope of this research. For a better understanding, the variables included in the CVI dataset are presented in Table 1, grouped by specific indicators and accompanied by acronyms to facilitate data processing and analysis (Table 2).

Table 2

Variables of CVI

|

ID |

Indicator |

Variables |

|

LCP |

Lethal crimes against the person |

Homicides, robberies, and attempted homicides |

|

NLCP |

Non-lethal crimes against the person |

Bodily injury, fights, violence, and threats |

|

SCC |

Serious crimes against custom |

Rape and indecent assault |

|

RC |

Robbery crimes |

Total asset thefts |

|

TC |

Theft crimes |

Total asset thefts |

|

WAC |

Weapons and ammunition crimes |

Illegal possession of weapons, illegal manufacturing of weapons and ammunition, seizure of firearms, and discharge of weapons |

|

DTC |

Drug trafficking crimes |

Trafficking of marijuana, cocaine, and other narcotics |

|

CPUD |

Crimes of possession and use of drugs |

Possession and use of marijuana, cocaine, and other narcotics |

|

CD |

Crime of drunkenness |

Drunkenness |

Note. Adapted from Índice de Violência Criminalizada (IVC) [Criminalized Violence Index (CVI)], by P. Lira, 2013, in II Congresso Consad de Gestão Pública – Painel 62: Gestão em segurança pública, Vitória (https://consad.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/%C3%8DNDICE-DE-VIOL%C3%8ANCIA-CRIMINALIZADA-IVC3.pdf).

The variables Theft Crimes (TC) and Robbery Crimes (RC) are categories of property crimes included in the CVI, which aims to facilitate the understanding of criminal dynamics. Within the composition of the CVI, the article states that both categories, RC and TC, are represented by the descriptive variable “Total Asset Thefts”. However, the core distinction between TC and RC lies in the manner in which the asset is taken: RC implies the use of violence or serious threat against a person, whereas TC involves the taking of the asset without such means. Thus, although both variables in the CVI share the same description, namely “total asset thefts”, the categorical differentiation is crucial for the analysis of criminalized violence, with RC being a crime of violence against the person and TC being a strictly property crime.

Once the data had been accessed, the OLS method was applied to estimate the relationship between the video surveillance implemented in the city of Aparecida de Goiânia and the selected explanatory variables. OLS is an estimation method widely used in econometrics, aiming to minimize the sum of the squares of the residuals, which are the differences between the observed values of the dependent variable and the values predicted by the model. OLS relies on a set of classical assumptions that guarantee its estimators are unbiased, consistent, and efficient. One of these assumptions is homoscedasticity, which requires the error term to exhibit constant variance across all observations. As per the analysis performed, this assumption was violated, indicating the presence of heteroscedasticity in the model’s error term.

To assess the robustness of the results and verify the adequacy of the model estimated via OLS, several diagnostic tests were performed on the residuals and explanatory variables. The characteristics of the tests used are:

- Breusch-Pagan test: This test is used to assess the presence of heteroscedasticity in the residuals. The null hypothesis assumes homoscedasticity, meaning that the error term exhibits constant variance. Rejecting the null hypothesis provides evidence of heteroscedasticity.

- Multicollinearity test (variance inflation factor, VIF): This test examines the existence of multicollinearity among the explanatory variables.

- RESET test: This is a residual-based test used to evaluate model specification. A high p value indicates that the model is adequately specified.

- Durbin-Watson test: This test evaluates the presence of autocorrelation in the residuals. The alternative hypothesis states that the autocorrelation coefficient (ρ) differs from zero. In addition to the original linear model, a log–log specification will also be estimated by transforming all variables into their natural logarithms. The same diagnostic tests will be applied to this transformed model to determine whether the logarithmic functional form improves the robustness of the results.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The data used in this analysis corresponds to a time series covering the period from 2014 to 2024, enabling the examination of trends in key social, economic, and public security indicators over the past decade. The dataset was structured around the variable lethal crimes against the person (LCP), which is part of the CVI, and was labeled “homicides” for clarity.

The variables used are detailed in the Table 3 and include indicators related to the number of homicides, education, health, employment, and income (based on the IFDM), as well as the variable representing the coverage of urban video surveillance. This database was statistically processed and organized with the support of the RStudio software, enabling the execution of econometric tests with methodological robustness and alignment with the best practices of quantitative research applied to regional analysis.

Table 3

Variables Used in the Analysis

|

Variable |

Description |

Behavior in analysis |

|

Homicides |

Number of homicides in the period |

Explanatory variable |

|

IFDM |

FIRJAN Municipal Development Index |

Explanatory variable |

|

CAM |

Presence or absence of cameras installed |

Explanatory variable |

|

EDU |

FIRJAN Education Index |

Explanatory variable |

|

SAL |

FIRJAN Salary Index |

Explanatory variable |

|

ER |

FIRJAN Employment and Income Index |

Explanatory variable |

The descriptive statistics of the variables were used to gain an initial understanding of their behavior, as presented in Table 2, which summarizes the following characteristics (Table 4):

Table 4

Descriptive Statistics

|

Variables |

Homicides |

CAM |

EDU |

SAL |

ER |

|

Mean |

267.5 |

1.00 |

0.4719 |

0.5843 |

0.7919 |

|

Minimum |

139.0 |

0.00 |

0.3726 |

0.5291 |

0.7395 |

|

Maximum |

342.0 |

1.00 |

0.6133 |

0.6694 |

0.8823 |

|

Variance |

5280.16 |

0.24 |

0.005858829 |

0.001683414 |

0.002853324 |

|

Standard deviation |

72.66470945 |

0.489897949 |

0.076542987 |

0.04102943 |

0.053416511 |

|

Coefficient of variation |

183.6963855 |

0.002939388 |

0.000358367 |

0.00024065 |

0.00043012 |

To estimate the relationship between the Homicides variable and the explanatory variables, the OLS method was used. OLS is a widely used estimation method in econometrics, that aims to minimize the sum of squared residuals, which represent the differences between the observed values of the dependent variable and those predicted by the model. The classical assumptions of OLS ensure that its estimators are unbiased, consistent, and efficient. One of the assumptions of OLS is homoscedasticity, which requires the error term to have constant variance.

The data analysis and econometric model estimation were conducted with the help of RStudio software, an open-source statistical tool widely used in the field of applied econometrics. RStudio was used to perform data pre-processing, which included organizing variables, conducting descriptive analyses, and checking for inconsistencies, as well as estimating regressions using the OLS method. The programming environment also allowed for the application of essential statistical tests to evaluate the model’s assumptions, such as homoscedasticity, normality of residuals, multicollinearity, and functional specification. The use of RStudio facilitated the transparency, reproducibility, and robustness of the empirical analysis, in line with the best practices of quantitative research.

A model was estimated with Homicides as the dependent variable and the remaining variables as explanatory variables, and all necessary diagnostic tests were conducted to assess the robustness of the results, as presented below.

Estimated Model

Homicides = 817.47 – 44.55 CAM – 516.85 EDU – 101.89 SAL - 293.32 ER + error

The estimated model was implemented using RStudio software, and the results are presented in the Table 5.

Table 5

Results of the Model Execution in RStudio

|

Estimate standard |

Error |

Value |

Pr (>t) |

|

|

(Intercept) |

817.47 |

258.22 |

3.166 |

0.0249 * |

|

CAM |

- 44.55 |

41.01 |

-1.086 |

0.3270 |

|

EDU |

- 516.85 |

335.97 |

-1.538 |

0.8470 |

|

SAL |

- 101.89 |

501.46 |

-0.203 |

0.8470 |

|

ER |

- 293.32 |

227.73 |

227.73 |

0.2541 |

|

Signif. codes: 0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1 ‘ ’ 1 |

||||

The results of the estimated model, including the behavior of the variables, are presented below, with the statistical significance levels indicated at the bottom of the table. Residuals are presented in the Table 6.

Table 6

Residuals

|

Residual standard error |

Multiple R2 |

Adjusted R2 |

F-statistic |

p value |

|

33.13 on 5 degrees |

0.8961 |

0.813 |

10.78 on 4 |

0.01128 |

To evaluate the robustness of the results and verify the adequacy of the model estimated by OLS, several diagnostic tests were performed on the residuals and explanatory variables. The characteristics of the tests used, as described in the sources, are:

- Breusch-Pagan test: This test is used to assess the presence of heteroscedasticity in the residuals. The null hypothesis assumes homoscedasticity, meaning that the error term exhibits constant variance. Rejecting the null hypothesis provides evidence of heteroscedasticity. An analysis where the value points to a “very low (<2)” p value leads to the rejection of the null hypothesis.

- Shapiro-Wilk test: This test assesses whether the residuals follow a normal distribution. In this analysis, a p value greater than 0.5 indicates that the residuals deviate from normality, thereby violating the normality assumption.

- Multicollinearity test (VIF): This test examines the existence of multicollinearity among the explanatory variables. If the analysis yields a VIF value greater than 10, it is considered indicative of severe multicollinearity. Conversely, a VIF value below 10 suggests the absence of severe multicollinearity, which is favorable for the stability of the estimated coefficients.

- RESET test: This is a residual-based test used to evaluate model specification. A high p value indicates that the model is adequately specified. If the analysis indicates a low p value (“ideally >= 0.05”), this suggests a potential specification problem, which may result from omitted relevant variables or from the relationship between variables not being strictly linear.

- Durbin-Watson test: This test checks for the existence of autocorrelation in the residuals. The alternative hypothesis of the test states that the autocorrelation coefficient (ρ) differs from zero. According to the cited sources, a p value greater than 0.05 in the normality test indicates that the residuals deviate from normality, while for the multicollinearity and autocorrelation tests, results are considered problematic if the p value is below 0.02. Applying a logarithmic functional form may improve the robustness of the results.

A linear model and a log-log model were estimated, as presented in Table 7:

Table 7

Comparison of Results Between the Linear and Log-Log Models

|

Test / Metric |

Linear model |

Log-Log model |

|

Breusch-Pagan test |

||

|

BP statistic |

4.0906 |

3.2673 |

|

df |

4 |

4 |

|

p value |

0.3939 |

0.5141 |

|

Shapiro-Wilk test |

||

|

W statistic |

0.94076 |

0.89527 |

|

p value |

0.5615 |

0.1943 |

|

Multicollinearity test (VIF) |

||

|

VIF (CAM / lCAM) |

3.67902 |

4.219989 |

|

VIF (EDU / lEDU) |

6.027090 |

5.489638 |

|

VIF (SAL / lSAL) |

3.857900 |

3.365490 |

|

VIF (ER / lER) |

1.348632 |

1.251529 |

|

RESET test |

||

|

RESET statistic |

3.6872 |

3.0856 |

|

df1 |

2 |

2 |

|

df2 |

3 |

3 |

|

p value |

0.1555 |

0.1871 |

|

Durbin-Watson test |

||

|

DW statistic |

1.663671 |

1.857104 |

|

p value |

0.044 |

0.112 |

Analysis of the Linear Model Results

The estimated equation for the linear model, using the OLS method, can be represented as follows:

Homicides = β₀ + β₁ VideoSurveillance + β₂ Education + β₂ Health + β₃ Employment/Income + error

Based on the data incorporated into the model, the equation can be represented as follows:

Homicides = 817.47 – 44.55 CAM – 516.85 EDU – 101.89 SAL - 293.32 ER + error

The OLS estimation results indicate that:

- The intercept is 817.47 and is statistically significant. The CAM variable has a coefficient of -44.55 and is also statistically significant, suggesting a negative relationship between the presence of cameras and the Homicides variable.

- The EDU variable has a coefficient of -516.85 and is highly statistically significant, suggesting a negative relationship between the FIRJAN Education Index and the Homicides variable.

- The SAL variable has a coefficient of -101.89 and is statistically significant, suggesting a negative relationship between the FIRJAN Health Index and the Homicides variable.

- The model’s goodness of fit, measured by the multiple R-squared, is 0.8961, and the adjusted R-squared is 0.813. The overall F-test is highly significant (F-statistic = 10.78, p = 0.01128), indicating that the explanatory variables, collectively, are relevant in explaining Homicides.

The diagnostic tests for the linear model yielded the following results and analyses:

- Breusch-Pagan test: BP = 4.0906, df = 4, p = 0.3939. Analysis: The test indicated that the residuals are heteroscedastic, indicating a problem of heteroscedasticity in the model. The null hypothesis of homoscedasticity is accepted, considering that the p value showed a considerable value (>2).

- Shapiro-Wilk test: W = 0.94076, p = 0.5615. Analysis: The test indicates that the residuals do not have a normal distribution due to the p > 0.5, thereby satisfying the normality assumption.

- Multicollinearity test (VIF): VIF for CAM = 3.679022, EDU = 6.027090, SAL = 3.857900, ER = 1.348632. Analysis: The VIF results do not indicate the presence of multicollinearity, as all values are below 10, which is favorable for the stability of the estimated coefficients.

- RESET test: RESET = 3.6872, df1 = 2, df2 = 3, p value = 0.1555. Analysis: The test indicates that the model has a specification problem, suggesting it may be misspecified, possibly with important variables omitted, given that the p value was very low (ideal p value >= 0.05). The relationship between the variables may not be strictly linear.

- Durbin-Watson test: DW statistic = 1.663671, p value = 0.044. Analysis: The test result suggests that the error has a normal distribution due to the p value < 5. According to additional analysis, the multicollinearity and autocorrelation tests would not be good because the p value should be greater than 2 (Note: As described in the methodology section, this analysis of the DW p value differs from the standard interpretation).

Based on the considerations above for the linear model, the results are not entirely satisfactory, suggesting that additional relevant variables should be included.

Analysis of the Log-Log Model Results

After transforming the variables to their natural logarithm, the estimated equation for the log-log model is as follows:

Homicides = 3.96143 – 0.07529 lCAM – 1.15769 lEDU – 0.68532 lSAL - 1.40505 lER + error

The OLS estimation results for the log-log model indicate that:

- The intercept is 3.96143, and is highly statistically significant. None of the other variables showed statistical relevance.

In terms of fit, the Multiple R2 for the log-log model is 0.8941, and the Adjusted R2 is 0.8094. These values are slightly higher than those of the linear model, suggesting a marginally better fit. The overall F-test of the log-log model does not show high statistical significance (F-statistic: 10.55, p value: 0.01181).

The diagnostic tests for the log-log model yielded the following results and analyses:

- Breusch-Pagan test: BP = 3.2673, df = 4, p = 0.5141. Analysis: Unlike the linear model, the test indicated that the residuals are heteroscedastic (heteroscedasticity problem). The null hypothesis of homoscedasticity is rejected, considering that the p value was very low (<2). The presence of heteroscedasticity violates one of the classical assumptions of the OLS method.

- Shapiro-Wilk test: W = 0.89527, p = 0.1943. Analysis: Unlike the linear model, the test indicates that the residuals have a normal distribution due to the p value < 0.5, thereby satisfying the normality assumption.

- Multicollinearity test (VIF): VIF for lCAM = 4.219989, lEDU = 5.489638, lSAL = 3.365490, and lER = 1.251529. Analysis: The VIF results do not indicate the presence of multicollinearity, as all values are below 10, which is favorable for the stability of the estimated coefficients.

- RESET test: RESET = 3.0856, df1 = 2, df2 = 3, p = 0.1871. Analysis: The test indicates that the log-log model also has a specification problem, suggesting it may be misspecified, possibly with important variables omitted, given that the p value was very low (ideal p value >= 0.05). The relationship between the variables may not be strictly linear.

- Durbin-Watson test: DW statistic = 1.857104, p = 0.112. Analysis: The result suggests that the error has a normal distribution due to the p value < 5. According to additional analysis, the multicollinearity and autocorrelation tests would not be good because the p value should be greater than 2 (Note: As described in the methodology section, this analysis of the DW p value differs from the standard interpretation).

Based on the considerations above, even after transforming the variables into the log–log form, the results of the diagnostic tests (heteroscedasticity, residual normality, and model specification) are not entirely satisfactory. The analysis suggests that the model, in both forms, still exhibits issues, indicating the need for improvements, such as the potential inclusion of additional explanatory variables to better capture the variation in Homicides and address the problems of heteroscedasticity and misspecification. The absence of severe multicollinearity represents a positive aspect in both models.

In summary, the results of the diagnostic tests indicate that neither OLS model (linear nor log–log) fully satisfies all of the classical assumptions, suggesting the need for improvements, such as the inclusion of additional explanatory variables, to achieve more robust and satisfactory results.

Threats to the Validity of the Results

Using the OLS method the results of the quantitative analysis are subject to significant threats to internal validity, preventing the findings from being considered fully satisfactory or robust without further methodological refinement. Internal validity was compromised due to violations of classical OLS assumptions. In the linear model, the Shapiro-Wilk test indicated that the residuals did not present a normal distribution, since the p value (0.5615) was greater than 0.5, thus failing to adhere to the normality assumption.

Although the transformation to the log-log model resolved the issue of residual normality (p value = 0.1943), it exposed a problem of heteroscedasticity, according to the Breusch-Pagan test analysis in the log-log model, which led to the rejection of the null hypothesis of homoscedasticity. The presence of heteroscedasticity, together with the deviation from normality in the linear model, is a key violation of the classical OLS assumptions, affecting both the efficiency and consistency of the estimators.

The main threat to construct and external validity arises from the model misspecification, suggesting the omission of important explanatory variables. The RESET test, applied to both the linear model (p value = 0.1555) and the log-log model (p value = 0.1871), indicated that both models have a specification problem. However, the results suggest that the relationship between the variables may not be strictly linear and that some relevant factors could be missing. Although the Multicollinearity test (VIF) yielded positive results in both cases (values below 10), the recurrence of heteroscedasticity and specification problems limits the predictive and explanatory capacity of the results found.

Therefore, the analysis conclusions suggest the imperative need to include additional variables in the model to better capture the variation in the Homicides variable and achieve more robust and satisfactory results.

CONCLUSION

Research such as the present study is essential for empirically and locally assessing the contributions of smart city initiatives within the broader context of regional development. In medium-sized urban territories, like Aparecida de Goiânia, the strategic use of emerging technologies—such as video surveillance—can not only enhance public safety but also drive structural transformations in local social and economic indicators. The interdisciplinary analysis of technology, public policies, and human development proves to be indispensable for guiding managers, planners, and institutions in understanding the real impacts of these initiatives, providing technical and scientific support for more effective and contextualized decisions.

In the specific case of Aparecida de Goiânia, the results indicate a negative correlation between the expansion of video surveillance camera coverage and homicide rates, suggesting a possible deterrent effect of this technology on urban crime. Furthermore, the analysis showed positive interactions between the advances of the smart city project and the FIRJAN Municipal Development Index (IFDM), particularly in health and education components, although with variations across the historical series. Despite the statistical limitations identified in the estimated models—such as the presence of heteroscedasticity and the need to refine the set of explanatory variables—the study fulfills its purpose by providing initial evidence of the potential of technological solutions to strengthen urban governance and promote collective well-being.

To complement the evaluation of the results, it is imperative to consider the Employment and Income (ER) dimension, a key component of the IFDM. Although subject to statistical limitations, the econometric analysis indicated a negative correlation between the Employment and Income Index and the Homicides variable (coefficient of –293.32 in the linear model). This result suggests that advances in economic development and income generation—core elements of human development as proposed by Amartya Sen—tend to move in the opposite direction of lethal violence. However, the ER coefficient did not demonstrate statistical relevance in any of the executed models, estimated models, with the p value in the linear specification equal to 0.2541. The absence of statistical significance for the ER coefficient corroborates the need pointed out in the discussion of results: model misspecification (as indicated by the RESET test, p value = 0.1555 in the linear model) and the violation of OLS assumptions require the inclusion of additional variables to robustly capture the contribution of Employment and Income to crime reduction, thereby aligning the smart city strategy with the promotion of quality of life and the reduction of inequalities.

REFERENCES

Abreu, J. P. M., & Marchiori, F. F. (2019). Ferramentas de avaliação de desempenho de cidades inteligentes: uma análise da norma ISO 37122:2019 [Performance assessment tools for smart cities: An analysis of ISO 37122:2019]. PARC Pesquisa Em Arquitetura E Construção, 14, e023002. https://doi.org/10.20396/parc.v14i00.8668171

Alves, L. A. (2019). Cidades saudáveis e cidades inteligentes: Uma abordagem comparativa [Healthy cities and smart cities: A comparative approach]. Sociedade & Natureza, 31, e47004. https://doi.org/10.14393/sn-v31-2019-47004

Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas. (2020). ABNT NBR 37122: Cidades e comunidades sustentáveis — Indicadores para cidades inteligentes [ABNT NBR 37122: Sustainable cities and communities — Indicators for smart cities]. Associação Brasileira De Normas Técnicas. https://abnt.org.br/certificacao/smartcities/

Brasil. Ministério do Desenvolvimento Regional. (2021). Carta Brasileira de Cidades Inteligentes. Ministério do Desenvolvimento Regional. https://www.gov.br/cidades/pt-br/acesso-a-informacao/acoes-e-programas/desenvolvimento-

urbano-e-metropolitano/projeto-andus/carta-brasileira-para-cidades-inteligentes

Chichoski, A., & Marquardt, J. F. (2023). O uso de tecnologias através do videomonitoramento do gabinete de segurança integrada municipal de Foz do Iguaçu – PR pelas agências de segurança pública e defesa social [The use of technologies through videomonitoring by the Integrated Municipal Security Office of Foz do Iguaçu – PR by public security and social defense agencies]. Revista (RE)Definições das Fronteiras, 1(1), 197-217. https://doi.org/10.59731/vol1iss1pp219-239

Covas, M. M. C. M., & Covas, A. M. A. (2020). Cidades inteligentes e criativas e smartificação dos territórios: Apontamentos para reflexão [Smart and creative cities and the smartification of territories: Notes for reflection]. DRd – Desenvolvimento Regional em Debate, 10(ed. esp.), 40-59. https://doi.org/10.24302/drd.v10ied.esp..2896

Ferreira, D. L. S., Novaes, S. M., & Macedo, F. G. L. (2023). Cidades inteligentes e inovação: A videovigilância na segurança pública de Recife, Brasil [Smart cities and innovation: Video surveillance in the public security system of Recife, Brazil]. Cadernos Metrópole, 25(58), 1095-1122. https://doi.org/10.1590/2236-9996.2023-5814

Filho, N. B., Santos, A. A. R., & Lima, H. C. P. (2024). Manaus como cidade inteligente – Vantagens e desvantagens do videomonitoramento aplicado à segurança pública [Manaus as a smart city – Advantages and disadvantages of video surveillance applied to public security]. Revista Contemporânea, 4(7), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.56083/RCV4N7-010

Gomes, M., Albernaz, L. R., Nascimento, A. C., & Torres, F. R. (2016). Accountability e transparência na implementação da Agenda 2030: As contribuições do Tribunal de Contas da União [Accountability and transparency in the implementation of the 2030 Agenda: Contributions from the Federal Court of Accounts]. Revista do Tribunal de Contas da União, 48(136), 76-91.

Guimarães, J. R. S., & Jannuzzi, P. M. (2005). IDH, indicadores sintéticos e suas aplicações em políticas públicas: Uma análise crítica [HDI, synthetic indicators and their applications in public policies: A critical analysis]. Revista Brasileira de Estudos Urbanos e Regionais, 7(1), 73-90. https://doi.org/10.22296/2317-1529.2005v7n1p73

Jordão, K. C. P. (2016). Cidades inteligentes: Uma proposta viabilizadora para a transformação das cidades brasileiras [Smart cities: A viable proposal for the transformation of Brazilian cities] [Master’s thesis, Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Campinas]. PUC Repository. https://repositorio.sis.puc-campinas.edu.br/handle/123456789/15131

Lazzaretti, K., Sehnem, S., Bencke, F. F., & Machado, H. P. V. (2019). Cidades inteligentes: Insights e contribuições das pesquisas brasileiras [Smart cities: Insights and contributions from Brazilian research]. Urbe. Revista Brasileira de Gestão Urbana, 11. https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-3369.011.001.e20190118

Lira, P. (2013). Índice de violência criminalizada (IVC) [Criminalized violence index (CVI)]. In II Congresso Consad de Gestão Pública – Painel 62: Gestão em segurança pública, Vitória, Brasil. https://consad.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/%C3%8DNDICE-DE-VIOL%C3%8ANCIA-CRIMINALIZADA-IVC3.pdf

Martinelli, M. A., Achcar, J. A., & Hoffmann, W. A. M. (2020). Cidades inteligentes e humanas: Percepção local e aderência ao movimento que humaniza projetos de smart cities [Smart cities and human-centered cities: Local perception and adherence to the movement that humanizes smart-city projects]. Revista Tecnologia e Sociedade, 16(39), 164-181. https://doi.org/10.3895/rts.v16n39.9130

Minayo, M. C. S. (2006). Violência e saúde [Violence and health] (Temas em Saúde series, Vol. 1). Editora Fiocruz. https://static.scielo.org/scielobooks/y9sxc/pdf/minayo-9788575413807.pdf

Oliveira, E. F. T. (2018). Estudos métricos da informação no Brasil: Indicadores de produção, colaboração, impacto e visibilidade [Metric studies of information in Brazil: Indicators of production, collaboration, impact, and visibility]. Editora Unesp. https://doi.org/10.36311/2018.978-85-7983-930-6

Paes, C. F. C., Gonçalves, P. H., & Ziebell, C. S. (2021). Smart city como ação determinante ao desenvolvimento do urbanismo sustentável [Smart city as a determinant action for the development of sustainable urbanism]. In Anais do IX Encontro de Sustentabilidade em Projeto – UFSC (pp. 257-268). Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina. https://repositorio.ufsc.br/bitstream/handle/123456789/227788/257-268.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Rezende, L. V. R., Cruz-Riascos, S. A., & Rodrigues, A. C. T. (2019). Dados abertos em cidades inteligentes: Uma análise da fronteira entre acesso e privacidade [Open data in smart cities: An analysis of the frontier between access and privacy]. e-LIS: e-prints in Library and Information Science. http://eprints.rclis.org/38639/

Roland Berger. (2019). Smart city strategy index: Vienna and London leading in worldwide ranking. https://www.rolandberger.com/en/Insights/Publications/Smart-City-Strategy-Index-Vienna-and-London-leading-in-worldwide-ranking.html

Sancino, A., & Lorraine, H. (2020). Leadership in, of, and for smart cities – Case studies from Europe, America, and Australia. Public Management Review, 22, 701-725. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2020.1718189

Silva, A. F. da, Sousa, J. S. de, & Araujo, J. A. (2017). Evidências sobre a pobreza multidimensional na região Norte do Brasil [Evidence on Multidimensional Poverty in the Northern Region of Brazil]. Revista de Administração Pública, 51, 219–239. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7612160773

Takiya, Carolina, A., Junior, S., & Marè, R. (2019). Cidades Inteligentes e o Índice Cities in Motion [Smart Cities and the Cities in Motion Index] – Case São Paulo. Revista Simetria do Tribunal de Contas do Município de São Paulo, 1(5), 65-81. https://doi.org/10.61681/revistasimetria.v1i5.46