UNIVQUAKE: SERIOUS VIRTUAL REALITY GAME

ABOUT EARTHQUAKES IN UNIVERSITY SCENARIOS

Sebastian Herrera Solis

https://orcid.org/0009-0009-9837-4257

Universidad de Lima, Peru

Hernan Quintana-Cruz

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7037-4302

Universidad de Lima, Peru

Received: August 31, 2025 / Accepted: November 3, 2025

doi: https://doi.org/10.26439/interfases2025.n022.8229

UNIVQUAKE: SERIOUS VIRTUAL REALITY GAME ABOUT

EARTHQUAKES IN UNIVERSITY SCENARIOS

ABSTRACT. Conventional earthquake drills often fail to provide safe, realistic, and repeatable training for procedural knowledge. This limitation is particularly critical in high-density settings, such as university environments, where it is vital to be prepared in the event of such disasters. Virtual reality (VR) combined with serious games (SGs) provides an opportunity for users to experience and practice responses to such events within a controlled environment. This research describes the design, development, and validation of VR-based SG for earthquake preparedness. The primary objective was to assess the effectiveness of the SG in improving university students’ knowledge of the measures to be taken in the event of earthquakes. The secondary objective was to analyze the correlation between the level of presence experienced in the SG and the knowledge gain. A pre-post study was conducted using a questionnaire validated by expert judgment to measure knowledge acquisition. The results demonstrated a statistically significant increase in participants’ average knowledge scores after using the VR-based SG. Additionally, a noteworthy finding was that no direct correlation could be confirmed between the level of presence reported by the participants and the knowledge they acquired. This research concludes that VR-based SG are an effective technological tool for improving procedural knowledge in earthquake preparedness in university settings, even when subjective presence is not a significant factor in the learning process.

KEYWORDS: earthquake, virtual reality, presence, serious game, undergraduate

UNIVQUAKE: juego serio de realidad virtual

sobre terremotos en escenarios universitarios

RESUMEN. Los simulacros de terremotos convencionales a menudo no proporcionan una formación segura, realista y repetible sobre los procedimientos a seguir. Esta deficiencia es especialmente grave en entornos de alta densidad, como los universitarios, donde la preparación ante este tipo de desastres resulta fundamental. La realidad virtual (RV), combinada con los juegos serios (JS), ofrece la oportunidad de «vivir» y practicar las respuestas a estos eventos en un entorno controlado. Esta investigación describe el diseño, desarrollo y validación de un JS basado en RV para la preparación ante terremotos. El objetivo principal era medir la eficacia del JS para mejorar los conocimientos de los estudiantes universitarios sobre las medidas que deben tomarse en caso de terremoto. El objetivo secundario era analizar la correlación entre el nivel de presencia experimentado en el JS y la adquisición de conocimientos. Se llevó a cabo un estudio pre-post utilizando un cuestionario validado por expertos para medir la adquisición de conocimientos. Los resultados demostraron un aumento estadísticamente significativo en las puntuaciones medias de conocimientos de los participantes después de utilizar el JS de RV. Además, un hallazgo notable fue que no se pudo confirmar una correlación directa entre el nivel de presencia reportado por los participantes y los conocimientos que obtuvieron. Este estudio concluye que los JS de RV son una herramienta tecnológica eficaz para mejorar los conocimientos procedimentales en materia de preparación para terremotos en entornos universitarios, incluso cuando la presencia subjetiva no es un factor significativo en el proceso de aprendizaje.

Palabras clave: realidad virtual, terremotos, juego serio, presencia, universitarios

INTRODUCTION

Peru is part of the so-called Pacific Ring of Fire (Guardia & Tavera, 2012, p. 1), which means that the possibility of an earthquake is a constant risk in the country. This vulnerability is shared by other countries, such as Japan, which is considered an international reference in disaster risk reduction due to its effective strategies for managing such disasters (Pastrana-Huguet et al., 2022). In contrast, Peru faces challenges in fostering an effective culture of prevention and safety, as only approximately 55% of the population participated in drills during 2019 (Instituto Nacional de Defensa Civil [INDECI], 2020).

This vulnerability presents a critical risk for high-density populations. In 2023, Peruvian private universities had combined a total of over 1.5 million enrolled students (National Institute of Statistics and Informatics [INEI], 2023). Given the unpredictability of earthquakes, they can occur at any time, including during class hours. Therefore, this research focuses on undergraduate students, as preparedness on university campuses is a key factor in mitigating risks.

Currently, the primary preparedness tool used in this context is national drills. However, most earthquake drills lack sufficient effectiveness and realism. Consequently, students and administrators do not gain a truly realistic experience during these activities (Gong et al., 2015, p. 2242).

Given the need for simulated environments that provide a realistic experience of these events, a number of studies have proposed the use of new technologies, including VR, to recreate disaster-training scenarios at a lower cost and with significantly reduced risk compared to real-world exercises. This approach has proved to be useful in both educational and training contexts (Lu et al., 2020). Additionally, users must be able to learn from the simulation in an interactive and engaging way. According to Checa and Bustillo (2020), serious games (SGs) offer a student-centered educational approach with specific, well-defined tasks that enhance learning. Through this approach, students engage in an interactive and motivating process that will improve their overall, active, and critical learning. Therefore, the objective of this study is to design, develop, and validate a VR-based SG for earthquake preparedness in a university scenario.

The article is organized into three main parts. First, it introduces a review of the relevant literature from the last seven years related to the research proposal. Next, it describes the methodology proposed for this research. Finally, it addresses the experimentation conducted.

STATE OF THE ART

This section provides a compilation of articles on VR-based SG for emergencies, VR-based SG focused on earthquakes, and VR-based earthquake simulators. It also summarizes recent advances and identifies existing research gaps.

Serious Immersive and Non-Immersive Games for Emergencies

VR-based SG can support training for emergency scenarios and enhance individuals’ chances of survival in highly hazardous situations (Irshad et al., 2021). Furthermore, VR technology offers an innovative approach to delivering this training in a scalable and resource-efficient manner (Rickenbacher-Frey et al., 2023). Table 1 presents a compilation of articles on the design, development, and implementation of VR-based SG for emergency situations.

Table 1

VR-based SG for Emergency Situations

|

Emergency |

Subjects |

I or N |

Type of navigation |

Scenario |

Origin |

Authors |

Contribution / Gap |

|

Rescue in confined spaces |

20 regular workers and 20 specialized workers |

I |

Limited to decisions |

Incident in Foshan, China |

China |

Lu et al. (2020) |

Gap: Participant cannot control movement |

|

Flooding |

55 volunteers |

N |

Open navigation via keyboard and mouse |

Urban buildings in Italy |

Italy |

D’Amico et al. (2023) |

Contribution: Focus on safe routes and object interaction |

|

Terrorist strike |

32 volunteers |

I |

Teleportation |

University building |

New |

Lovreglio et al. (2022) |

Contribution: University scenario |

|

Fire |

30 people aged 60 to 80 |

I |

Teleportation |

Realistic residences |

China |

Fu & Li (2023) |

Contribution: Dynamic events |

|

Fire |

140 junior students |

I |

- |

High-rise building |

Taiwan |

Chen & Chien (2022) |

Contribution: Teaching situations based on levels |

|

Fire |

78 hospital staff members |

N |

Open navigation via keyboard and mouse |

Vincent Van Gogh Hospital |

Belgium |

Rahouti et al. (2021) |

Contribution: Immersive experience positively affects |

Note. I = immersive, N = non-immersive.

VR-Based SG for Earthquake Training

Serious games in VR about earthquakes

Table 2 presents a compilation of articles that address the design, development, and implementation of immersive VR-based SG focused on earthquake preparedness training.

Table 2

Immersive VR-based SG for Earthquakes

|

Subjects |

Type of |

Scenario |

Origin |

Authors |

Contribution / Gap |

|

91 |

Predefined |

High school and |

- |

Feng, González, Mutch et al. (2020) |

Contribution: 6-framework for customizable learning |

|

93 |

Predefined |

Fifth floor of Auckland City Hospital |

New Zealand |

Feng, González, Amor et al. (2020) |

Contribution: Qualitative strategy for damages |

|

147 |

Open using remote control |

Shopping mall |

- |

Ahmadi et al. (2023) |

Gap: No object interaction |

|

42 |

Teleportation |

Juvenile room |

Greece |

Maragkou et al. (2023) |

Contribution: Interactive mechanics |

The literature reveals a lack of studies that integrate natural locomotion systems with object interaction across different scenarios.

During this section, the reviewed literature uses VR to measure and observe participant behavior. For example. Zhang et al. (2021) developed a VR simulator to evaluate the safe actions people take during an earthquake in an office and in a room, aiming to understand people’s behavior during an earthquake. Similarly, Mitsuhara et al. (2021) created a system to observe behaviors during the evacuation of people, highlighting the differences between a single-person and a two-person simulation. Their primary goal is to understand what people do in these types of emergencies.

On the other hand, the literature also focuses on the environmental replication of real scenarios. Xu et al. (2023) implemented a method using mixed reality where they scanned the simulation area and showed safe and dangerous zones where the participant should be located, highlighting the ability to represent an environment in VR. Also, Suzuki et al. (2018) conceived an earthquake simulator that generates a copy of the indoor environment using artificial intelligence (AI) technologies and allows it to be projected into the VR world.

Meanwhile, other literature validates the educational impact. Rajabi et al. (2022) decided to evaluate the effect of VR education on decisions during an earthquake, using a classroom in Tehran as a case study. Liuwandy et al. (2020) explored an affordable way to conduct earthquake simulations in VR, creating an earthquake simulator that can be run on cell phones. Finally, Shu et al (2019) compared the presence and effectiveness of an earthquake simulator viewed on a computer screen with that of a VR headset. They concluded that VR simulators help people become familiar with earthquake simulations.

A review of the literature reveals significant deficiencies. We identified a shortcoming in locomotion and navigation, with most applications opting for restrictive navigation methods. Secondly, physical interactivity is clearly limited. Current applications focus on decision-making rather than on interactions with the environment. Finally, reviewed simulators are primarily used for behavioral observation. This suggests an opportunity to gamify these simulations, transforming them into effective training tools.

3. MATERIALS AND METHODS

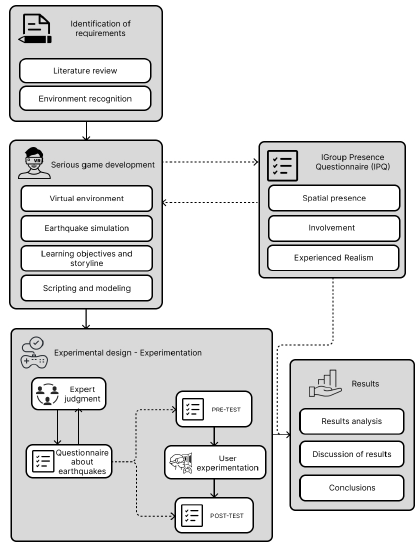

The methodology proposed for this research can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Methodological Scheme

Identification of Requirements

During the requirements identification process, the material provided by INDECI was reviewed, from which the relevant recommendations and instructions for these disaster scenarios were extracted. This information is essential for defining the learning objectives and developing the game’s storyline.

As shown in Table 3, the learning objectives incorporate INDECI’s recommendations for actions to be taken before, during, and after an earthquake.

Table 3

Learning Objectives During the Stages of an Earthquake

|

Stage |

Learning objectives |

|

Before an earthquake |

|

|

During an earthquake |

|

|

After an earthquake |

|

Note. Learning objectives based on interviews and a review of official guidelines (INDECI, 2024).

Additionally, the learning objectives address other preparedness activities, such as identifying the essential items that should be included in an emergency kit: (i) water, (ii) canned food, (iii) coats, (iv) a flashlight, (v) a battery-powered radio, (vi) a whistle, and (vii) a first-aid kit. Furthermore, the objectives include identifying safe areas inside buildings in the event of an earthquake, such as (i) columns, (ii) life-triangle zones, (iii) areas away from glass or falling objects, (iv) doorways, (v) locations under beams, and (vi) areas outside elevator shafts (INDECI, 2024).

Regarding the recognition of environments, the approach taken by Xiao et al. (2017) was followed, in which the author proposed a complete review of the infrastructure of the environments. Classrooms L3-402 and O2-202 at the Universidad de Lima were selected for analysis and research, along with their respective evacuation routes and points of interest, due to the availability and accessibility of infrastructure data.

SG Development

During the development of the virtual environment, basic 3D models were used to create the buildings aiming to replicate reality as closely as possible, along with textures designed to simulate the surrounding environment. Several objects within the environments were sourced from Sketchfab (https://sketchfab.com/) and Unity Asset Store (https://assetstore.unity.com/). As seen in Figure 2, these models in the virtual classroom must exhibit physics, dimensions, and behaviors consistent with their real-world counterparts (Rajabi et al., 2022).

According to Lovreglio (2018), this study will use earthquake simulation using a qualitative strategy. This approach involves simulating the damage caused by the disaster without incorporating information about the structures in the simulated environment. In addition, this strategy was used because it is more suitable for designing a SG, as it allows threats to be represented strategically to enhance training effectiveness (Lovreglio, 2018). The Modified Mercalli Intensity (MMI) scale was used to choose the earthquake magnitude, as it aligns with the qualitative approach, based on work of Feng, González, Mutch et al. (2020). The scale chosen for this research is MM9, as this causes partial damage to buildings, total breakage of glass, and cracks in walls (Dowrick et al., 2008).

Based on Lu et al. (2020) and Rahouti et al. (2021), a story for the game is proposed using the scenarios and learning objectives (see Table 3). The story, which lasts approximately 30 minutes, consists of the following elements:

- At the beginning, participants must prepare their emergency kit before proceeding to their classroom.

- Participants begin outside their classroom building and are required to proceed toward it.

- During their journey, they must recognize safe areas and ensure that there are no obstacles along the evacuation route.

- When they arrive at their classroom and take their seats, an earthquake begins. Participants must remain calm and decide whether to take shelter under a table, move to a safe area, or evacuate as quickly as possible using the available controls. Depending on their choice, they may need to repeat this level.

- After the earthquake, participants must wait for any aftershocks or move toward the exit.

- During the evacuation, participants must avoid any objects that may fall or cause injury, while keeping their heads protected as a precaution.

- Once the evacuation is complete, participants must proceed to an emergency meeting point and call the emergency numbers, if necessary, to end the game. They will also have the option to return to the building, in which case they will restart the level.

At the end of the game, the players will be provided with a report detailing their actions throughout the simulation, along with the total evacuation time (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Screenshots of UnivQuake

Note. UnivQuake scenes: “Emergency kit” (top left), “L3 hallway” (top right), “O2 hallway” (middle left), “L3 classroom after earthquake” (middle right), “O2 classroom after earthquake” (bottom left), and “Evacuation complete” (bottom right).

Unity Game engine was used to create the game, as this Integrated Development Environment (IDE) provides the audio, physics, and graphics tools required to create an enjoyable experience in a space in which users can freely navigate the virtual space (Ilongwe et al., 2023). Within Unity, version 2021.3.23f1 was used, along with the XR Interaction Toolkit, an interaction system for creating augmented and VR experiences through interactive objects that operate using Unity events (Unity, 2023).

Regarding the sounds implemented for the earthquake simulation, the audio files were sourced from Zapslat (https://www.zapslat.com/) and were used to illustrate the noises that occur during an earthquake.

During the development stage, a pilot test was conducted to measure the presence level of the SG using the Igroup Presence Questionnaire (IPQ), an instrument designed to assess the sense of presence experienced by users in a virtual environment. The IPQ consists of one general item and three subscales: (i) Spatial Presence, (ii) Involvement, and (iii) Experienced Realism (Igroup, 2016). This pilot test enabled adjustments to several presence-related aspects of the SG.

Questionnaire About Earthquakes

The questionnaire used in this research to measure knowledge consists of five open-ended questions related to the learning objectives, as shown in Table 4. The score for each question will be determined by the number of correct responses provided by the participants for that question. The use of this type of questionnaire is supported by De Fino et al. (2023), Feng, González, Mutch et al. (2020), and Lu et al. (2020). These studies use pre-test and post-test questionnaires, methodologically designed to measure the knowledge acquired through their respective SGs.

Table 4

Earthquake Knowledge Questionnaire

|

Questions |

Score |

|

What actions should you take before an earthquake? |

|

|

What to do during an earthquake? |

|

The questionnaire was validated by expert judgment. The scale used was the Content Validity Ratio (CVR) proposed by Lawshe (1975). The five questions were evaluated by twelve INDECI members, each receiving a CVR value of 0.80. Therefore, these questions are essential and were included in the questionnaire.

|

What to do after an earthquake? |

|

|

What items should be included in an emergency kit? |

|

|

What are the safe areas inside a building in the event of an earthquake? |

|

Participants

The target population consisted of undergraduate students who attended computer-equipped classrooms during 2024. The sample included 30 undergraduate students (25 male, 5 female), aged 20 to 25 years. All participants reported prior experience in computer-equipped classrooms. Consistent with Tavares (2022), the sample was familiar with digital interaction, as most participants are young individuals who frequently engage with digital technologies such as video games. Regarding the technology used in the study, only four participants reported prior experience with VR headsets.

Experimentation

To assess the knowledge of the measures to be taken during earthquakes, a quasi-experimental repeated-measures design was implemented. A pre-test using the proposed questionnaire was conducted to determine the participants’ initial knowledge level. Subsequently, a post-test was conducted after participants completed the SG in VR.

To evaluate the presence experienced in the SG, the IPQ was used, as in the pilot test, since this instrument allows effective measurement of participants’ sense of presence in virtual environments.

Additionally, the study aims to analyze the relationship between the level of presence experienced by the test participants and the improvement in knowledge of earthquake safety measures. To this end, a correlation analysis will be conducted between the IPQ scores and the differences between pre-test and post-test results.

The different hypotheses proposed are described below:

- Null hypothesis 1 (H0₁): There is no significant difference between the participants’ knowledge before and after the SG test.

- Alternative hypothesis 1 (H1₁): There is a significant improvement in the participants’ knowledge after participating in the SG.

- Null hypothesis 2 (H0₂): No significant correlation was found between the level of presence experienced in the SG and the improvement in knowledge of earthquake safety measures.

- Alternative hypothesis 2 (H1₂): A significant positive correlation was found between the level of presence experienced in the SG and the improvement in knowledge of earthquake safety measures.

To participate in the game, a device enabling immersive visualization of the virtual environment is required. Therefore, Meta Quest 2 headsets were used in the research, allowing for tracking of both head and hand movements.

For interaction with the virtual environment and free movement, the Touch controllers included with the headsets were used. Regarding sound stimuli, Logitech Astro A10 headphones were used during the experiment.

RESULTS

This section presents knowledge assessment results corresponding to Hypothesis 1. As shown in Table 5, the Shapiro-Wilk test was first applied to data to determine their normal distribution. The resulting p value for this test is reported in the “Normality” column. If the normality value was less than 0.05, the non-parametric Wilcoxon test was applied; if it was greater than 0.05, the paired t-test was used. Subsequently, the selected test was used to validate the existence of an improvement. The table compares these pre-test and post-test scores, where M is the mean score and SD is the standard deviation

Table 5

Earthquake Knowledge Questionnaire Results

|

Learning objectives |

Pre-test |

Post-test |

Normality |

p value |

T- values/ W values |

Statistical test |

|

Before the earthquake |

M = 1.53 |

M = 2.26 |

0.0003974 |

0.00005912 |

W = 9 |

Wilcoxon |

|

During the earthquake |

M = 1.86 |

M = 2.36 |

.0346 |

.009472 |

W = 39 |

Wilcoxon |

|

After the earthquake |

M = 1.53 |

M = 2.63 |

.04416 |

.0005698 |

W = 32.5 |

Wilcoxon |

|

Emergency kit |

M = 3.50 |

M = 5.36 |

.08104 |

.000001844 |

T = 5.6951 |

Paired t-test |

|

Indoor safe zones in case of earthquakes |

M = 1.23 |

M = 2.43 |

.02167 |

.0001014 |

T = 5.1739 |

Paired t-test |

|

Total |

M = 9.66 |

M = 15.06 |

0.2961 |

9.61E-10 |

T = 8.5727 |

Paired t-test |

An improvement in knowledge was observed across all evaluated areas. In the assessment of knowledge prior to the earthquake, the mean score increased from 1.53 to 2.26, with a p < .05, indicating a significant improvement in knowledge levels. This effect may be attributed to the fact that this stage involved the greatest level of participant interaction with objects within the game.

During the earthquake knowledge assessment, this item showed the smallest increase, with the mean score rising from 1.86 to 2.36 and a p < .05. This could be caused by the fact that during this stage, participants were in distress due to the earthquake, which led them to focus on escaping the environment rather than performing the recommended actions. In the post-earthquake knowledge assessment, the mean score increased from 1.53 to 2.63, with a p < .05, which suggested a significant improvement.

The question related to the emergency kit showed the greatest increase in the mean score compared to the other questions. This effect may be attributed to participants’ engagement with the activity of preparing the emergency kit. Finally, the assessment related to indoor safe zones during earthquakes showed an increase in the mean score from 1.23 to 2.43, with a p < .05, which suggested a significant improvement, even though the activity related to this assessment was addressed superficially. Our findings on knowledge improvement are consistent with those reported by Feng, González, Mutch et al. (2020) and Lu et al. (2020). However, these findings contrast with those reported by Ahmadi et al. (2023), who indicated that their post-game assessment did not show a significant increase in safety knowledge.

Hypothesis 2 proposes a significant correlation between the perceived level of presence and improved knowledge of earthquake preparedness measures. Spearman’s correlation test was applied, given that the data from the knowledge questionnaire did not show a normal distribution across all objectives. These results did not show significant evidence between the two variables, with a correlation coefficient ρ = 0.236 and a coefficient of determination r² = 0.0557, implying that only 5.5% of the variability in knowledge can be explained by the overall level of presence. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 is not supported by the findings of this study.

CONCLUSIONS

The purpose of this research was to design, develop, and validate a VR-based SG for earthquake preparedness in university scenarios. The primary objective was to assess participants’ knowledge, and the secondary objective was to analyze the correlation between the level of presence experienced in the SG and improved knowledge.

To this aim, two simulated environments were created in which participants could experience an earthquake and complete tasks before, during, and after the earthquake. The pre-post study used a questionnaire validated by expert judgment to measure knowledge.

A statistically significant increase in participants’ average knowledge scores was observed after testing the SG. In addition, an important finding was that a direct correlation between the level of presence and the knowledge gain.

The importance of this work lies in the provision of a technological solution for earthquake risk management education in university settings and emphasizes the scientific value of VR SG in as an effective tool for disaster preparedness training.

One of the main limitations is the hardware processing capacity, which restricts the generation of more realistic scenarios and the inclusion of non-player characters.

These limitations provide directions for future research. Additionally, the implementation of immediate feedback is proposed to enable participants to identify and correct their mistakes in real time. It is suggested to include more activities that reinforce knowledge in stages and investigate which factors directly influence learning within VR.

In conclusion, this research validates VR SGs as a practical and effective tool for building procedural knowledge in disaster preparedness within university settings.

REFERENCES

Ahmadi, M., Yousefi, S., & Ahmadi, A. (2023). Investigation of the most effective training method for rescuing people in earthquake emergency using immersive virtual reality serious games [Preprint]. SSRN. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4555342

Checa, D., & Bustillo, A. (2020). A review of immersive virtual reality serious games to enhance learning and training. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 79(9-10), 5501–5527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-019-08348-9

Chen, S.-Y., & Chien, W.-C. (2022). Immersive virtual reality serious games with DL-assisted learning in high-rise fire evacuation on fire safety training and research. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.786314

D’Amico, A., Bernardini, G., Lovreglio, R., & Quagliarini, E. (2023). A non-immersive virtual reality serious game application for flood safety training. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 96, 103940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2023.103940

De Fino, M., Tavolare, R., Bernardini, G., Quagliarini, E., & Fatiguso, F. (2023). Boosting urban community resilience to multi-hazard scenarios in open spaces: A virtual reality – serious game training prototype for heat wave protection and earthquake response. Sustainable Cities and Society, 99, 104847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2023.104847

Dowrick, D. J., Hancox, G. T., Perrin, N. D., & Dellow, G. D. (2008). The Modified Mercalli intensity scale. Bulletin of the New Zealand Society for Earthquake Engineering, 41(3), 193-205. https://doi.org/10.5459/bnzsee.41.3.193-205

Feng, Z., González, V. A., Amor, R., Spearpoint, M., Thomas, J., Sacks, R., Lovreglio, R., & Cabrera-Guerrero, G. (2020). An immersive virtual reality serious game to enhance earthquake behavioral responses and post-earthquake evacuation preparedness in buildings. Advanced Engineering Informatics, 45, 101118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2020.101118

Feng, Z., González, V. A., Mutch, C., Amor, R., Rahouti, A., Baghouz, A., Li, N., & Cabrera-Guerrero, G. (2020). Towards a customizable immersive virtual reality serious game for earthquake emergency training. Advanced Engineering Informatics, 46, 101134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2020.101134

Fu, Y., & Li, Q. (2023). A virtual reality–based serious game for fire safety behavioral skills training. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 40(19), 5980-5996. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2023.2247585

Guardia, P., & Tavera, H. (2012). Inferencias de la superficie de acoplamiento sísmico interplaca en el borde occidental del Perú. Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica del Perú, 106, 3748. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12816/914

Gong, X., Liu, Y., Jiao, Y., Wang, B., Zhou, J., & Yu, H. (2015). A novel earthquake education system based on virtual reality. IEICE Transactions on Information and Systems, E98.D(12), 2242-2249. https://doi.org/10.1587/transinf.2015edp7165

Igroup. (2016). Igroup Presence Questionnaire (IPQ) overview [Questionnaire]. https://www.igroup.org/pq/ipq/index.php

Ilongwe, A., Sepulveda, C., & Kashani, T. (2023). The calling VR: A musical virtual reality experience. SIGGRAPH ‘23: Special Interest Group on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques Conference. https://doi.org/10.1145/3588027.3595598

Instituto Nacional de Defensa Civil. (2020). Estadísticas de gestión reactiva de la gestión del riesgo de desastres – Año 2019 [Reactive management statistics of disaster risk management – Year 2019] [Report]. https://portal.indeci.gob.pe/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/CAPITULO-II-Estad%C3%ADsticas-GR-2019.pdf

Instituto Nacional de Defensa Civil. (2024, January 14). ¿Qué hacer en caso de sismo? [What to do in case of an earthquake?]. Gob.pe. https://www.gob.pe/1053-que-hacer-en-caso-de-sismo

Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. (2023). Número de alumnos/as matriculados en universidades privadas, 2008-2023 [Number of students enrolled in private universities, 2008-2023] [Data set]. Retrieved September 15, 2023, from https://m.inei.gob.pe/estadisticas/indice-tematico/university-tuition/

Irshad, S., Perkis, A., & Azam, W. (2021). Wayfinding in virtual reality serious game: An exploratory study in the context of user perceived experiences. Applied Sciences, 11(17), 7822. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11177822

Lawshe, C. H. (1975). A quantitative approach to content validity. Personnel Psychology, 28(4), 563-575. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1975.tb01393.x

Liuwandy, P., Suryasari, & Wella. (2020). Affordable mobile virtual reality earthquake simulation. 2020 Fifth International Conference on Informatics and Computing (ICIC). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIC50835.2020.9288562

Lovreglio, R., Gonzalez, V., Feng, Z., Amor, R., Spearpoint, M., Thomas, J., Trotter, M., & Sacks, R. (2018). Prototyping virtual reality serious games for building earthquake preparedness: The Auckland City Hospital case study. Advanced Engineering Informatics, 38, 670-682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2018.08.018

Lovreglio, R., Ngassa, D.-C., Rahouti, A., Paes, D., Feng, Z., & Shipman, A. (2022). Prototyping and testing a virtual reality counterterrorism serious game for active shooting. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 82, 103283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103283

Lu, S., Xu, W., Wang, F., Li, X., & Yang, J. (2020). Serious game: Confined space rescue based on virtual reality technology. 2020 2nd International Conference on Video, Signal and Image Processing. https://doi.org/10.1145/3442705.3442716

Maragkou, V., Rangoussi, M., Kalogeras, I., & Melis, N. S. (2023). Educational seismology through an immersive virtual reality game: Design, development and pilot evaluation of user experience. Education Sciences, 13(11), 1088. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111088

Mitsuhara, H., Tanioka, I., & Shishibori, M. (2021). Observing evacuation behaviours of surprised participants in virtual reality earthquake simulator. Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Computers in Education, 2, 576-582. https://doi.org/10.58459/icce.2021.4294

Pastrana-Huguet, J., Casado-Claro, M.-F., & Gavari-Starkie, E. (2022). Japan’s culture of prevention: How bosai culture combines cultural heritage with state-of-the-art disaster risk management systems. Sustainability, 14(21), 13742. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113742

Rahouti, A., Lovreglio, R., Datoussaïd, S., & Descamps, T. (2021). Prototyping and validating a non-immersive virtual reality serious game for healthcare fire safety training. Fire Technology, 57(2), 3041-3078. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10694-021-01098-x

Rajabi, M. S., Taghaddos, H., & Zahrai, S. M. (2022). Improving emergency training for earthquakes through immersive virtual environments and anxiety tests: A case study. Buildings, 12(11), 1850. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12111850

Rickenbacher-Frey, S., Adam, S., Exadaktylos, A. K., Müller, M., Sauter, T. C., & Birrenbach, T. (2023). Development and evaluation of a virtual reality training for emergency treatment of shortness of breath based on frameworks for serious games. GMS Journal for Medical Education, 40(2), Doc16. https://doi.org/10.3205/zma001598

Shu, Y., Huang, Y.-Z., Chang, S.-H., & Chen, M.-Y. (2019). Do virtual reality head-mounted displays make a difference? A comparison of presence and self-efficacy between head-mounted displays and desktop computer-facilitated virtual environments. Virtual Reality, 23(4), 437-446. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-018-0376-x

Suzuki, R., Iitoi, R., Qiu, Y., Iwata, K., & Satoh, Y. (2018). AIbased VR earthquake simulator. In J. Y. C. Chen & G. Fragomeni (Eds.), Lecture notes in computer science: Vol. 10910. Virtual, augmented and mixed reality: Applications in health, cultural heritage, and industry (pp. 213-222). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91584-5

Tavares, N. (2022). The use and impact of game-based learning on the learning experience and knowledge retention of nursing undergraduate students: A systematic literature review. Nurse Education Today, 117, 105484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2022.105484

Unity. (2023). XR Interaction Toolkit (version 2.4) [Software documentation]. https://docs.unity3d.com/Packages/[email protected]/manual/index.html

Xiao, M.-L., Zhang, Y., & Liu, B. (2017). Simulation of primary school-aged children’s earthquake evacuation in rural town. Natural Hazards, 87(3), 1783-1806. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-017-2849-8

Xu, Z., Yang, Y., Zhu, Y., & Fan, J. (2023). Mixed reality drills of indoor earthquake safety considering seismic damage of nonstructural components. Scientific Reports, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-43533-9

Zhang, F., Xu, Z., Yang, Y., Qi, M., & Zhang, H. (2021). Virtual reality-based evaluation of indoor earthquake safety actions for occupants. Advanced Engineering Informatics, 49, 101351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2021.101351