INTERRELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN TOTAL PRODUCTIVE

MAINTENANCE, JIDOKA AND ECONOMIC

SUSTAINABILITY: EMPIRICAL VALIDATION OF AN

INTEGRATED CONCEPTUAL MODEL

Jorge Luis García Alcaraz

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7092-6963

Departamento de Ingeniería Industrial, Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez, México

Jorge Limón Romero

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2117-4803

Facultad de Ingeniería, Arquitectura y Diseño, Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, México

Juan Carlos Quiroz-Flores

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1858-4123

Facultad de Ingeniería Industrial, Universidad de Lima, Perú

Yolanda Báez López

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8418-254X

Facultad de Ingeniería, Arquitectura y Diseño, Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, México

Arturo Realyvásquez Vargas

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2825-2595

Departamento de Ingeniería Industrial, Tecnológico Nacional de México/IT Tijuana, México

Received: June 28, 2025 / Accepted: August 11, 2025

Published: December 19, 2025

doi: https://doi.org/10.26439/ing.ind2025.n049.8063

This research received no external funding.

* Corresponding author e-mails: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

ABSTRACT. This study develops and empirically validates an integrated conceptual model that investigates the causal relationships among Total Productive Maintenance (TPM), Jidoka, and economic sustainability (ECSU) within the manufacturing industry. Based on Resource and Capability Theory as well as Systems Theory, the model posits that TPM directly influences both jidoka and ECSU, while jidoka acts as a mediator in the relationship between TPM and ECSU. Utilizing structural equation modeling (SEM-PLS) and data collected from 357 surveys of the maquiladora industry in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, the analysis confirms that TPM positively affects jidoka (β=٠,632, p<0,001) and ECSU (β=0,340, p<0,001). Furthermore, jidoka contributes significantly to ECSU (β=0,358, p<0,001) and mediates the effect of TPM on ECSU (β=0,226), resulting in an increased total effect of β=0,566. The researchers conducted graphical analyses that demonstrate nonlinear patterns in relationships. These findings underscore the synergies between TPM and jidoka, which work together to maximize sustainable economic benefits in lean manufacturing environments.

KEYWORDS: TPM / jidoka / manufacturing industries / manufacturing processes / lean manufacturing / sustainable development / structural equation modeling

INTERRELACIONES ENTRE EL MANTENIMIENTO

PRODUCTIVO TOTAL, JIDOKA Y LA SOSTENIBILIDAD

ECONÓMICA: VALIDACIÓN EMPÍRICA DE UN MODELO

CONCEPTUAL INTEGRADO

RESUMEN. Este estudio desarrolla y valida empíricamente un modelo conceptual integrado que examina las relaciones causales entre el mantenimiento productivo total (TPM), jidoka y la sostenibilidad económica (ECSU) en la industria manufacturera. Basado en la teoría de recursos y capacidades y la teoría de sistemas, el modelo propone que TPM influye directamente en jidoka y ECSU, mientras que jidoka media la relación TPM-ECSU. Utilizando modelado de ecuaciones estructurales (SEM-PLS) y datos de 357 encuestas en la industria maquiladora de Ciudad Juárez, México, se confirmó que TPM impacta positivamente a jidoka (β=٠,632, p<0,001) y ECSU (β=0,340, p<0,001), mientras que jidoka también contribuye a ECSU (β=0,358, p<0,001). Además, jidoka media el efecto de TPM en ECSU (β=0,226), aumentando el efecto total a β=0,566. Los análisis gráficos revelaron patrones no lineales en las relaciones. Estos hallazgos destacan las sinergias entre TPM y jidoka para maximizar beneficios económicos sostenibles en entornos de manufactura esbelta.

PALABRAS CLAVE: TPM / jidoka / industria manufacturera / procesos industriales / producción eficiente / desarrollo sostenible / modelos de ecuaciones estructurales

INTRODUCTION

In the contemporary industrial landscape, businesses must actively optimize operational efficiency and enhance their competitiveness to address the escalating pressures of global economics and environmental challenges. Total Productive Maintenance (TPM), first conceptualized by Nakajima (1989), represents a strategy that integrates physical asset management to systematically eliminate the six primary operational losses associated with machines: equipment breakdowns, setup and adjustment times, minor stoppages, speed reductions, quality defects, and start-up losses (Ahuja & Khamba, 2008). TPM transcends conventional approaches of corrective and preventive maintenance by adopting a holistic philosophy that actively engages all organizational levels in maximizing Overall Equipment Efficiency (OEE).

Empirical evidence demonstrates that companies successfully implementing TPM significantly enhance various dimensions of organizational performance, including reduced operational costs, increased productivity, and improved product quality (Pramod et al., 2010). However, the complexity of implementing TPM necessitates a comprehensive understanding of the interrelationships among its fundamental pillars and its integration with other continuous improvement philosophies, such as lean manufacturing (LM), concurrently applied on production lines.

Lean manufacturing (LM) is a management methodology designed to maximize customer value by systematically eliminating waste in production processes. It encompasses various tools, including Total Productive Maintenance (TPM), which originated in the Toyota Production System. This philosophy prioritizes the optimization of resource utilization, the reduction of lead times, and the enhancement of quality in response to market demands. By focusing on waste elimination, the TPM approach aligns closely with LM principles. Consequently, TPM has emerged as one of the most prevalent tools in production lines within the LM framework (Valverde-Curi et al., 2019).

The integration of LM and waste elimination has fostered a natural convergence between TPM and the concept of jidoka, which embodies automation with a human touch and serves as a fundamental pillar of the Toyota Production System (Shingo & Dillon, 1989). jidoka represents the capacity of production systems to automatically detect anomalies and halt the process until the system identifies and corrects the root cause. This approach effectively prevents the propagation of defects and minimizes the generation of waste (Cantini et al., 2024). It is important to recognize that these defects often result from inadequate machine maintenance (Pascal et al., 2019).

The conceptual synergy between TPM and jidoka stems from their mutual emphasis on operational autonomy and proactive problem detection. TPM aims to maximize equipment availability and reliability, while jidoka enhances this perspective by ensuring that production systems operate only under optimal quality conditions (Womack et al., 2017). This theoretical convergence indicates the presence of significant causal relationships that require rigorous empirical validation.

The implementation of TPM and jidoka in industry aims to convert waste into savings and financial benefits. Consequently, in the contemporary business landscape, economic sustainability (ECSU) emerged as a central factor shaping strategic decision-making. This shift moves beyond the traditional focus on short-term profit maximization towards a sustainable approach to value creation (Chaabane et al., 2021). Within the industrial context, ECSU is understood as an organization’s capacity to sustain competitive financial performance while optimizing resources and minimizing negative environmental and social impacts.

Existing research demonstrates that effectively implementing TPM generates sustainable economic advantages through various mechanisms, such as reducing maintenance costs, optimizing asset life cycles, minimizing waste, and enhancing energy efficiency (Chaabane et al., 2021). Similarly, the application of jidoka principles significantly improves ECSU by mitigating non-quality costs, minimizing rework, and optimizing productive resources.

Despite a rich body of literature on TPM and jidoka as separate methodologies in industrial applications, researchers have overlooked the integrated modeling of their interrelationships and the combined impact on ECSU. Previous studies have primarily concentrated on identifying critical success factors for the individual implementation of each methodology (Gelaw et al., 2024) and examining their isolated effects on specific performance indicators.

The existing literature lacks integrative conceptual models that simultaneously examine the causal relationships among TPM, jidoka, and ECSU from a systemic perspective. This gap is particularly critical, as Resource-Based View (RBV) theory asserts that sustainable competitive advantages emerge from the synergistic integration of complementary organizational resources and capabilities (Arief et al., 2023). This study develops and empirically validates an integrated conceptual model aimed at exploring the causal relationships among TPM, jidoka, and ECSU within the industrial sector.

This study advances theoretical understanding by empirically validating an integrated conceptual model and presents significant scientific and social implications. Scientifically, the research demonstrates how the synergy between TPM and jidoka functions as complementary organizational capabilities that enhance ECSU. This finding addresses a notable gap in the literature concerning the quantification of their interaction.

On a social level, these findings are particularly relevant to the manufacturing and maquiladora industries, which play a crucial role in regions such as Ciudad Juárez. The research offers a practical framework that maximizes sustainable economic benefits, improves job stability, and strengthens regional competitiveness. By effectively integrating TPM and jidoka, organizations can optimize resources, reduce costs, and cultivate a culture of continuous improvement and personnel empowerment. These factors notably enhance worker well-being and corporate social responsibility.

This paper is structured into six main sections: introduction, methodology, results, discussion of results and conclusions that include managerial implications, limitations, and future research. The methodology section details the research design, operationalization of latent variables, and the procedures for data collection. The results present a descriptive statistical analysis alongside the validation and evaluation of the measurement model. In the conclusions, the paper synthesizes the findings, outlines the limitations, and suggests avenues for future research.

This model identifies three interconnected latent variables through three hypotheses, supported by the Resources and Capabilities Theory (RBV) and the Systems Theory (ST). The RBV plays a crucial role in clarifying how TPM and jidoka foster sustainable competitive advantages that lead to ECSU. Specifically, the RBV defines TPM and jidoka as organizational capabilities or strategic intangible assets, which empower firms to develop distinctive competencies that directly influence their economic performance (Samadhiya et al., 2023).

ST is helpful in explaining the causal structure and interrelationships among the variables under investigation. Specifically, ST makes it clear that TPM needs to influence jidoka, thereby enabling both to effectively impact on ECSU. Absent a systemic perspective, the model lacks conceptual coherence; we must understand the sequential causal relationships and synergistic effects among TPM, jidoka, and ECSU from a holistic viewpoint (Zhou et al., 2022). Within this framework, each component is influenced by other concepts in the system is, thereby generating positive feedback loops.

The interrelationship between TPM and jidoka is clarified through the Resource-Based View (RVB) framework. The implementation of TPM allows for the optimization of both physical and human resources, which in turn enables real-time detection and rectification of errors. From a systems theory perspective, TPM serves as a critical subsystem that enhances the reliability and stability of the production system. This improvement establishes essential conditions for jidoka to bolster quality and improve responses to failures.

The interrelationship between TPM and jidoka relies on the operational interdependence of these methodologies within the lean manufacturing framework. TPM plays a crucial role in ensuring the availability and reliability of operations, equipment, and systems, which establishes the technological stability necessary for the effective functioning of the automatic detection mechanisms integral to jidoka. By prioritizing the maximization of equipment efficiency, TPM facilitates the successful integration of jidoka principles. According to Quiroz-Flores and Vega-Alvites (2022), lean manufacturing methodologies like TPM effectively reduce production costs and enhance overall productivity, thereby increasing the flexibility required to implement timely quality controls that are fundamental to jidoka. Additionally, TPM strategies promote proactive engagement among operators, strengthening their ability to identify, diagnose, and address anomalies within the production process, a critical aspect of the jidoka approach.

TPM and jidoka actively seek to minimize the downtime caused by equipment malfunctions and defects. Hallioui et al. (2023) demonstrate that implementing TPM improves overall equipment effectiveness (OEE), aligning with the goal of producing high-quality results while minimizing waste. Oroye et al. (2022) assert that maintaining machinery in optimal conditions minimizes operational disruptions, allowing workers to focus on quality control, and enabling the early detection of process defects. Additionally, Rada et al. (2024) reveal that industries experience improvements in operational performance following the adoption of Total Productive Maintenance (TPM). This implementation not only fosters the integration of jidoka, but also boosts productivity, and helps achieve sustainability objectives. Consequently, these insights highlight the importance of a robust TPM framework as a foundational element for the successful implementation of jidoka. Based on this analysis, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1. The implementation of TPM has a direct and positive effect on jidoka.

The relationship between TPM and ECSU hinges on TPM’s ability to maximize asset utilization, reduce costs, and enhance productivity. This dynamic ultimately strengthens the economic income of the organization, in line with RSV theory. Furthermore, from an ST perspective, TPM enhances the overall operation of the production system, thereby ensuring its long-term viability and economic competitiveness.

Organizations implement TPM with the expectation of achieving economic benefits through improved equipment efficiency and waste reduction, which translates into significant savings. To achieve these objectives, TPM actively trains employees to take responsibility for equipment maintenance. This emphasis on training enhances operational reliability, minimizes production losses, streamlines operations, and improves overall equipment effectiveness (OEE). This allows organizations to maximize productivity, reduce costs (Mendes et al., 2023), and increase profitability for manufacturers (Zhang & Chin, 2021).

TPM effectively aligns with lean manufacturing principles to eliminate non-value-added activities, fostering continuous optimization and economic performance (Bekar, 2023). Companies that implement TPM actively reduce waste and improve their resource efficiency, which is essential for gaining a competitive advantage and ensuring compliance with Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance (ESG) criteria (Danguche & Taifa, 2023). The current integration of TPM with the Internet of Things (IoT) and Industry 4.0 enables real-time monitoring and analysis of defects, which extends equipment lifespan and allows for more effective maintenance scheduling, ultimately resulting in cost savings by preventing unforeseen failures (Samadhiya et al., 2023). Based on this information, we can propose the following hypothesis:

H2. The implementation of TPM has a direct and positive effect on ECSU.

The association between jidoka and ECSU becomes clear as jidoka actively enhances quality and minimizes waste, which improves competitiveness and directly contributes to the organization’s ECSU from the perspective of RSV. Additionally, jidoka strengthens the adaptability and efficiency of the production system from the standpoint of ST, enabling an agile response to anomalies and ensuring the system’s economic sustainability.

Jidoka emphasizes the importance of training both machines and operators to swiftly identify defects during the production process. This proactive approach not only prevents quality issues but also reduces costs linked to waste, rework, and inefficiencies. This suggests that implementing jidoka promotes ECSU. Additionally, jidoka’s economic benefits extend to heightened employee engagement and empowerment, as it allows employees to halt production in the event of problems. This practice cultivates a culture of continuous improvement and accountability. Such empowerment enhances job satisfaction and retention, ultimately boosting labor productivity (Tamás et al., 2020).

When industries adopt jidoka they position themselves more effectively to navigate the transition to Industry 4.0 by integrating advanced technologies and automation tools. This transition fosters the development of resilient production systems that can adapt to fluctuating economic conditions and demands (Koteswarapavan & Pattanaik, 2024). By enhancing flexibility and responsiveness to market changes, jidoka becomes a strategic asset for firms aiming to sustain long-term economic growth amidst environmental uncertainties (Cantini et al., 2024). This analysis leads us to propose the following hypothesis:

H3. The implementation of jidoka has a direct and positive effect on ECSU.

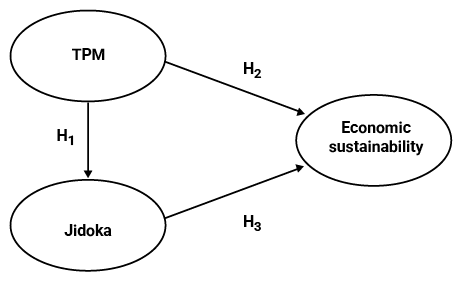

A graphical representation of the proposed hypotheses is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Relationships between variables and hypotheses

METHODOLOGY

The relationships among the latent variables--TPM, jidoka, and ECSU-- are- illustrated in Figure 1 as a structural equation model (SEM), a methodology well-documented in existing research. Balouei Jamkhaneh et al. (2018) employed SEM to evaluate the impact of computerized maintenance on organizational performance, and we adopted their methodology to validate our hypotheses through the following activities.

This study examines three latent variables: TPM, jidoka, and ECSU. We conducted a comprehensive literature review to identify prior studies related to these variables and the methods for assessing them. Specifically, we sourced TPM and jidoka from Martínez-Loya et al. (2018) and obtained ECSU from Díaz-Reza et al. (2022). To ensure the relevance of these items to the specific geographical context and contemporary events, we undertook a validation process involving three academic experts and five industry managers.

Given its significant economic and social impact, we administered a questionnaire to the manufacturing sector in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, targeting approximately 309 maquiladora companies. We conducted the survey online using Google Forms, inviting each prospective participant to participate via email. The data collection period ran from February 1 to May 1, 2025, and specifically focused on managers and engineers employed in the maintenance department.

On May 2, 2025, I researchers downloaded a dataset from the Google Forms platform and validated each variable according to the indices proposed by Kock (2023). To assess predictive validity, we employed R2 and adjusted R2, aiming for values that exceed 0,2. For internal validity, we utilized Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability indices, ensuring they are greater than or equal to 0,7. We measured convergent validity using the average variance extracted, which should exceed 0,5. To evaluate multicollinearity among the items, we applied variance inflation indices, which must remain below 5. Some of these indices are obtained iteratively, as removing specific items within the latent variables enhances their overall quality.

In this study, we employed a structural equation model (SEM) to validate the hypotheses delineated in Figure 1. This approach is particularly appropriate for latent variables, especially when certain variables, such as those associated with jidoka, simultaneously serve as both independent and dependent variables (Hair & Alamer, 2022). We selected the partial least squares (PLS) approach because of the ordinal nature of the data and its effectiveness in situations where variables do not adhere to a normal distribution or when the sample size is small (Kock & Hadaya, 2018). All computations in this study were performed with a confidence level of 95%.

Before interpreting the PLS-SEM, we ensured compliance with the quality and efficiency indices outlined by Kock (2023). We assessed the average path coefficient (APC), average R-squared (ARS), and average adjusted R-squared (AARS) to evaluate predictive validity, noting that the p-value was below 0,05. Additionally, we examined the average block VIF (AVIF) and the average full collinearity VIF (AFVIF) to assess collinearity, confirming that these values remained below 5. Lastly, we utilized the Tenenhaus GoF index (GoF) to evaluate the model’s data fit, ensuring it exceeded the threshold of 0,36.

In the SEM analysis conducted using WarpPLS v.8 software, we identified three types of effects between variables at a 95 % confidence level, following the procedures outlined by Hair et al. (2017). First, the direct effects validate the hypotheses. Second, the indirect effects arise through a mediating variable, such as jidoka. Finally, the total effects encapsulate both direct and indirect effects, providing a comprehensive view of the relationships among the variables.

For each type of effect—direct, indirect, and total—we calculated a standardized β value to quantify the dependence between the latent variables. We assessed the significance of these effects using the p-value, testing the null hypothesis H0: β=0 was tested against the alternative hypothesis H1: β≠0. If the analysis shows that β=0, we conclude that no relationship exists between the latent variables. Conversely, if we find that β≠٠, we conclude that a relationship does exist (Kock, 2023).

For each relationship between latent variables, this study reports the effect size (ES) as a measure of the variance explained by the independent variable, as proposed by (Kock, 2023). Similarly, the study presents the value of R2 for the dependent variables to quantify the variance explained by the independent variables that impact it. To determine the necessary sample size, the study utilized the minimum value of β from the direct effects, applying the inverse square root and gamma exponential methods (Kock & Hadaya, 2018).

WarpPLS v.8 software enables researchers to compute probabilities for latent variables based on their degree of implementation. In this study, we define a high level of implementation for a variable when the standardized Z value exceeds one, denoted as P(Z>1). Conversely, we identify a low level of implementation when the standardized Z value falls below -1, represented as P(Z<-1), as utilized by Kock (2023). This study presents the following three probabilities proposed by Kock (2023).

1. The probability that a variable manifests at either a high or low level of implementation.

2. The probability that two variables simultaneously manifest with a combination of high and low levels of implementation.

3. The conditional probability that the dependent variable occurs at any level, given that the independent variable has occurred at any other level.

RESULTS

Out of 1,231 mailings distributed, researchers received a total of 368 responses, yielding a response rate of 29,89 %. However, the analysis excluded 11 respondents identified as non-committed responders, leading to a final sample of 357 respondents, which includes 197 males and 160 females. Table 1 presents a comprehensive breakdown of the sectors and positions held by the respondents, highlighting that managers and maintenance engineers comprised the most prevalent roles, with significant representation from the automotive sector.

Table 1

Positions and industry sector

|

Position |

Sector |

Total |

||||||||

|

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

H |

I |

||

|

Manager |

29 |

20 |

12 |

6 |

18 |

11 |

13 |

14 |

24 |

147 |

|

Engineer |

52 |

2 |

18 |

17 |

7 |

4 |

20 |

12 |

30 |

162 |

|

Supervisor |

12 |

1 |

3 |

7 |

2 |

2 |

7 |

4 |

10 |

48 |

|

Total |

93 |

23 |

33 |

30 |

27 |

17 |

40 |

30 |

64 |

357 |

A: Automotive, B: Aeronautics, C: Electrical, D: Electronics, E: Logistics, F: Machinery, G: Medical, H: Rubber and Plastics, I: Textiles.

Table 2 presents the median as a measure of central tendency for the items included in the questionnaire, analyzing the grouped data. It also displays the interquartile range (IQR) of the items, which serves as a measure of dispersion. The variables marked with an asterisk (*) were eliminated during the validation process, specifically TPM1, ECS3, and ECS8, to enhance reliability or reduce collinearity (Parsazadeh et al., 2018).

Table 2

Descriptive analysis of the items

|

Item |

Median |

IQR |

|

TPM |

||

|

* TPM1. We ensure that machines are always in a high state of readiness for |

4,15 |

1,67 |

|

TPM2. We conduct regular inspections to keep machines running smoothly |

4,14 |

1,59 |

|

TPM3. We have a sound daily maintenance system to prevent machine failures |

3,96 |

1,80 |

|

TPM4. We thoroughly clean work areas (including machines and equipment) to |

4,04 |

1,67 |

|

TPM5. We have a specific time set aside each day for maintenance activities. |

3,89 |

1,98 |

|

TPM6. Operators receive training to keep the machines running. |

3,94 |

1,70 |

|

TPM7. We highlight our excellent maintenance system as a strategy for achieving |

4,03 |

1,66 |

|

Jidoka |

||

|

JID1. Does the machinery alert you when a part does not meet requirements? |

4,07 |

1,73 |

|

JID2. Does the machinery stop automatically when it detects an error in |

4,10 |

1,70 |

|

JID3. Are small machines used to ensure a fast and uniform flow of materials? |

4,02 |

1,75 |

|

JID4. Do operators have the authority to stop the machine in case of problems? |

4,25 |

1,39 |

|

JID5. Is visual control used to assess the status of production processes? |

4,27 |

1,44 |

|

JID6. When a failure occurs, can each member obtain specific information to |

4,18 |

1,51 |

|

ECSU |

||

|

ECS1. Reduction in production costs |

4,30 |

1,40 |

|

ECS2. Improvement in profits |

4,26 |

1,40 |

|

* ECS3. Reduction in product development costs |

4,26 |

1,45 |

|

ECS4. Reduction in energy costs |

4,24 |

1,43 |

|

ECS5. Reduction in inventory costs |

4,21 |

1,42 |

|

ECS6. Reduction in rejection and rework costs |

4,18 |

1,46 |

|

ECS7. Reduction in raw material costs |

4,23 |

1,46 |

|

* ECS8. Reduction in waste treatment costs |

4,23 |

1,44 |

|

ECS9. Reduction in administrative penalties for environmental incidents |

425 |

1,45 |

Table 3 provides the validation indices for the latent variables. The final column includes the desired values, allowing us to conclude that both parametric and non-parametric predictive validity, along with adequate internal validity, and convergent validity that exceeded the minimum threshold. Furthermore,v, the analysis showed no collinearity issues among the variables. For each variable, the table specifies the number of initial and final items following validation; for example, TPM initially included seven items, but after the removal of TPM1, only six items were analyzed. Similarly, ECS initially consisted of nine items, but after eliminating ECS3 and ECS8 due to collinearity issues, only seven items were analyzed. Additionally, the Jarque-Bera normality test (normal–JB) confirms the appropriateness of the PLS approach over the covariance-based approach (CB-PLS).

Table 3

Validation of the latent variables

|

Index |

TPM |

Jidoka |

ECSU |

Best if |

|||

|

Initial/final items |

7 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

9 |

7 |

|

|

R2 |

0,399 |

0,395 |

>0,2 |

||||

|

Adjusted R2 |

0,396 |

0,39 |

>0,2 |

||||

|

Composite reliability |

0,951 |

0,927 |

0,954 |

>0,7 |

|||

|

Cronbach’s alpha |

0,938 |

0,905 |

0,944 |

>0,7 |

|||

|

Average variance extracted |

0,763 |

0,678 |

0,75 |

>0,5 |

|||

|

Variance inflation index |

1,777 |

1,863 |

1,603 |

<5 |

|||

|

Q2 |

0,398 |

0,394 |

≈ R2 |

||||

|

Normal - JB |

No |

No |

No |

||||

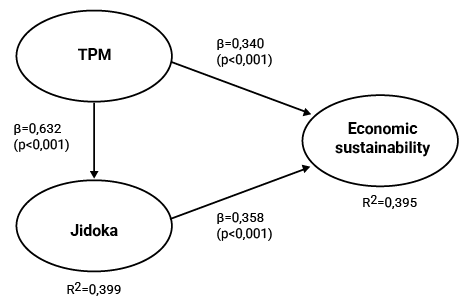

After validating the latent variables, we conducted the SEM analysis to assess its efficiency and quality indices. The results demonstrate that the model can be interpretable, as it meets all the necessary criteria. Figure 2 illustrates the model, and the indices are as follows:

- The average path coefficient (APC)=0,443 (P < 0,001).

- Average R-squared (ARS)=0,397, P<0,001.

- The average adjusted R-squared (AARS) was 0,393 (P < 0,001).

- Average block VIF (AVIF)=1,648, acceptable if ≤ 5.

- Average full collinearity VIF (AFVIF)=1,747, which is acceptable if < 5.

- Tenenhaus GoF (GoF)=0,539 and large ≥ 0,36.

Figure 2

Validation of hypotheses

Figure 2 illustrates the direct effects among the latent variables, displaying each standardized β value alongside its corresponding p-value and R² value for the dependent variables. The p-values demonstrate that all relationships are statistically significant, achieving a confidence level of up to 99,9 %. Table 4 summarizes the conclusions drawn concerning the proposed hypotheses.

Table 4

Validation of hypotheses

|

Hypotheses |

β (p-value) |

ES |

Conclusion |

|

H1. TPM→jidoka |

0,632 (p<0,001) |

0,399 |

Supported |

|

H2. TPM→ECSU |

0,340 (p<0,001) |

0,191 |

Supported |

|

H3. jidoka→ECSU |

0,358 (p<0,001) |

0,204 |

Supported |

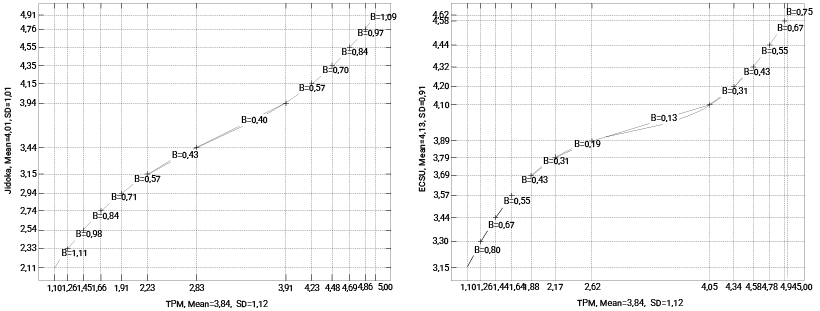

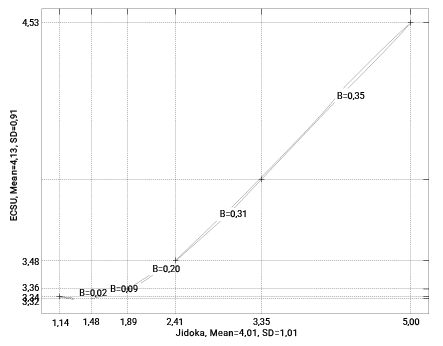

Figures 3,4, and 5 illustrate the graphical relationships among the variables for the TPM→jidoka relationship in H1, the TPM→ENSU relationship in H2, and the jidoka→ENSU relationship in H3, respectively. These plots effectively demonstrate the variation in β values on a five-point Likert scale.

Figure 3 Figure 4

TPM→jidoka ratio TPM→ECSU ratio

Figure 5

Jidoka-ECSU relationship

In this model, jidoka serves as a mediator in the relationship between TPM and ECSU, exhibiting a coefficient of β=0,226 (p<0,001), which indicates statistical significance. This mediation is significant, as the direct effect of TPM and ECSU measures only 0,340, resulting in an increased total effect between these variables to 0,566. Table 5 summarizes the total effects among the variables, incorporating the indirect effect and underscoring the prominence of TPM’s influence on both jidoka and ECSU, which are characterized by the highest effect values.

Table 5

Total effects

|

To |

From |

|

|

TPM |

Jidoka |

|

|

Jidoka |

0,632 (p<0,001) ES=0,399 |

|

|

ECSU |

0,565 (p<0,001) ES=0,319 |

0,358 (p<0,001) ES=0,204 |

Table 6 details the sensitivity analysis performed on both low and high levels of variable implementation, as outlined by the hypotheses in Figure 1. The analysis indicates low levels of a variable with a “-” minus sign, while high levels are indicated by the “+” plus sign. In this framework, joint occurrence probabilities use the ampersand “&”, while conditional probabilities are denoted by “IF” for dependent scenarios. The analysis reveals that the independent probability of TPM+ occurring is 0,212, whereas the probability of TPM- is 0,154. Furthermore, the probability of both jidoka+ and TPM+ occurring concurrently is 0,104. When considering the occurence of jidoka+ given that TPM+ has taken place, the probability rises to 0,490. In contrast, the probability of jidoka- occurring under the condition of TPM+ is only 0,020. This finding indicated that high levels of TPM implementation do not correlate with low levels of jidoka. Similar interpretations apply to other relationships examined within the analysis.

Table 6

Sensitivity analysis

|

To |

Probability |

From |

|||

|

TPM+ |

TPM- |

Jidoka+ |

Jidoka- |

||

|

0,212 |

0,154 |

0,163 |

0,163 |

||

|

Jidoka + |

0,163 |

&=0,104 IF=0,490 |

&=0,008 IF=0,054 |

||

|

Jidoka - |

0,163 |

&=0,004 IF=0,020 |

&=0,067 IF=0,432 |

||

|

ECSU+ |

0,175 |

&=0,092 IF=0,431 |

&=0,013 IF=0,081 |

&=0,083 IF=0,513 |

&=0,008 IF=0,051 |

|

ECSU- |

0,163 |

&=0,000 IF=0,000 |

&=0,071 IF=0,459 |

&=0,008 IF=0,051 |

&=0,083 IF=0,513 |

DISCUSSION OF RESULTS

This study’s empirical findings, obtained through SEM, demonstrate the interrelationships among TPM, jidoka, and ECSU within the manufacturing context. The results show that TPM exerts a direct and positive influence on jidoka (β=0,632, p<0,001), accounting for 39,9 % of its variance. This finding aligns with previous literature that highlights the complementarity between these lean methodologies, particularly the work of Cua et al. (2001). Additionally, the nonlinear relationship illustrated in Figure 3 reveals coefficients that range from β=1,11 at low levels of TPM to β=1,09 at high levels, indicating a diminishing returns effect as both methodologies develop and mature.

From a theoretical perspective, this relationship is based on the premise that TPM ensures the operational stability and equipment reliability essential for the effective implementation of jidoka. The preventive and predictive maintenance integral to TPM fosters optimal technological conditions for efficient automatic anomaly detection systems. The observed positive correlation, albeit with varying intensities, reveals that organizations investing in TPM concurrently enhance their automatic defect-detection capabilities. This synergy cultivates a virtuous cycle of continuous improvement, wherein both methodologies reinforce one another. Consequently, well-maintained equipment is better equipped to detect and respond to anomalies with greater accuracy, thereby facilitating a more effective implementation of the jidoka principles.

The analysis demonstrates a direct and positive relationship between TPM and ECSU, with a standardized coefficient of β=0,340 (p<0,001), accounting for 19,1 % of ECSU variability. Additionally, TPM exerts an indirect effect through jidoka, with a coefficient of β=0,226, culminating in a total effect of 0,565 and explaining up to 31,9 % of the ECSU variability.

Figure 4 illustrates three distinct phases of the relationship: an initial phase of early adoption that yields substantial economic returns (β=0,80–0,67), an intermediate learning plateau where benefits stabilize (β=0,13–0,19), and an advanced optimization phase in which mature TPM sustains economic benefits (β=0,43–0,75). This three-phase pattern aligns with organizational technology adoption theory, which posits that initial improvements target fundamental inefficiencies, followed by a period where organizations develop competence, ultimately achieving advanced optimization. In essence, TPM directly influences ECSU by reducing operating costs, minimizing losses due to unplanned downtime, and optimizing the asset lifecycle, corroborating the findings of Díaz-Reza et al. (2022).

The findings clearly indicate that jidoka exerts a direct and positive influence on ECSU (β=0,358, p<0,001), accounting for up to 20,4 % of its variability. Figure 5 depicts an exponential growth relationship, with coefficients rising from β=0,03 at initial levels to β=0,34 at higher levels of jidoka, which signifies an acceleration in economic benefits. This exponential pattern underscores key characteristics of jidoka, where initial economic gains remain modest due to the investments necessary to yield significant impacts. During the early stages, organizations built essential anomaly detection capabilities but experienced limited economic benefits because of the learning costs and initial investments in automated systems. As systems mature, however, a multiplier effect emerges; the capability to automatically halt production upon detecting defects results in exponential savings, prevents the mass production of defective products, reduces reprocessing costs, minimizes material waste, and enhances overall quality.

A significant finding of this study demonstrates that jidoka mediates the relationship between TPM and ECSU (β=0,226, p<0,001). This mediation enhances the total effect of TPM on ECSU, increasing it from 0,340 to 0,566. This enhancement indicates that certain economic benefits of TPM flow through the capabilities of jidoka. Consequently, maquiladoras can maximize their economic returns on TPM investments by concurrently implementing jidoka systems, thus creating synergies that amplify sustainable economic benefits.

The sensitivity analysis offers compelling evidence of these relationships, indicating a probability of 0,490 for jidoka occurring at high levels. However, the probability of jidoka occurring at low levels when TPM is at high levels is only 0,020. These findings clearly demonstrate the strong positive dependence between the two methodologies and support a joint implementation strategy to maximize organizational benefits.

CONCLUSIONS

This study presents an integrated conceptual model that empirically validates the causal relationships among TPM, jidoka, and ECSU within the manufacturing industry. The findings provide scientific evidence supporting the synergies between these lean methodologies. Specifically, the study affirms the three proposed hypotheses: it demonstrates that TPM directly and positively influences jidoka (β=0,632), that TPM directly impacts ECSU (β=0,340), and that jidoka significantly contributes to ECSU (β=0,358). Furthermore, the analysis identifies jidoka’s mediating effect in the TPM-ECSU relationship (β=0,226), which enhances the total effect to β=0,566.

The findings substantiate the joint application of Resource and Capability Theory alongside Systems Theory to elucidate the interrelationships among lean methodologies. The results reveal that TPM and jidoka serve as complementary organizational capabilities, and their integrated implementation yields sustainable competitive advantages that produce greater economic benefits compared to their isolated applications. This study advances scientific knowledge by providing empirical evidence of the systemic nature of lean practices, demonstrating that value is maximized through synergistic integration rather than through the independent use of individual tools.

The graphical analyses presented in this study reveal nonlinear patterns in the relationships, offering valuable information for strategic management. In the case of the TPM-jidoka relationship, the saturation curve identifies an optimal balance point at which investments in both methodologies yield maximum returns. Regarding TPM-ECSU, the three-phase pattern highlights the necessity for tailored implementation strategies that align with the organization’s maturity level, acknowledging that economic benefits fluctuate significantly throughout the adoption process. In the jidoka-ECSU relationship, the exponential nature of the interaction underscores the critical importance of persistence and long-term vision in the implementation process, as substantial benefits typically materialize only after organizations navigate initial learning and investment challenges.

The study faces several limitations, primarily due to its restricted geographical focus on the Maquiladora industry in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. This narrow concentration limits the generalizability of the findings to other industrial and cultural contexts. The cross-sectional design employed in the research constrains the ability to establish definitive causal relationships among the examined variables. The absence of moderating variables, such as organizational size, technological maturity, and the specific industrial sector, diminishes the strength of the observed relationships. Additionally, this study predominantly emphasizes economic benefits and pays little attention to the environmental and social dimensions of sustainability that are increasingly pertinent in contemporary discourse.

Future research should involve longitudinal studies to capture the temporal evolution of the relationships between TPM, jidoka, and ECSU, thereby establishing definitive causality. Additionally, researchers should perform cross-cultural comparative analyses to validate the model across various geographical and industrial contexts. It is essential to integrate moderating variables such as digitalization, Industry 4.0, and dynamic organizational capabilities into future studies. Researchers should also strive to develop comprehensive sustainability models that encompass both environmental and social dimensions through triple impact constructs.

The study presents robust empirical evidence underscoring the significance of implementing TPM and jidoka as strategies to enhance ECSU in lean manufacturing environments. It offers a theoretical and practical framework for optimizing organizational resources and attaining sustainable competitive advantages, which ultimately contribute to improved economic performance and sustainable industrial development.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

CREDIT AUTHOR STATEMENT

Jorge Luis García Alcaraz: Writing-original drafting, writing, proofreading, editing, conceptualization, data curation, methodology, and research. Jorge Limón Romero: Writing, revision and editing, supervision, conceptualization, and visualization. Yolanda Báez López: Writing, proofreading, and editing, supervision, and visualization. Juan Carlos Quiroz Flores: Software, writing, revision, and editing. Arturo Realyvásquez Vargas: Writing-original drafting, proofreading, editing, and conceptualization.

REFERENCES

Ahuja, I. P. S., & Khamba, J. S. (2008). Total productive maintenance implementation in a manufacturing organisation. International Journal of Productivity and Quality Management, 3(3), 360–381. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPQM.2008.017504

Arief, I., Hasan, A., Putri, N. T., & Rahman, H. (2023). Literature reviews of RBV and KBV theories reimagined: A technological approach using text analysis and Power BI visualization. International Journal on Informatics Visualization, 7(4), 2532–2542. https://dx.doi.org/10.62527/joiv.7.4.1940

Balouei Jamkhaneh, H., Khazaei Pool, J., Khaksar, S. M. S., Arabzad, S. M., & Verij Kazemi, R. (2018). Impacts of computerized maintenance management system and relevant supportive organizational factors on total productive maintenance. Benchmarking, 25(7), 2230–2247. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-05-2016-0072

Bekar, E. T. (2023). Efficiency measurement based on novel performance measures in Total Productive Maintenance (TPM) Using a fuzzy integrated COPRAS and DEA method. Frontiers in Manufacturing Technology, 3, article 1072777. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmtec.2023.1072777

Cantini, A., Ahmadi, A., Presciuttini, A., & Portioli-Staudacher, A. (2024). Jidoka advancements and applications for empowering manufacturing and operations: a bibliometric review. In XXIX AIDI Summer School Francesco Turco – Industrial systems engineering. https://www.summerschool-aidi.it/images/papers/session_3_2024/1108_Cantini.pdf

Chaabane, K., Schutz, J Dellagi, S., & Trabelsi, W.. (2021). Analytical evaluation of TPM performance based on an economic criterion. Journal of Quality in Maintenance Engineering, 27(2), 413–429. https://doi.org/10.1108/JQME-08-2019-0085

Cua, K. O., McKone, K. E., & Schroeder, R. G. (2001). Relationships between implementation of TQM, JIT, and TPM and manufacturing performance. Journal of Operations Management, 19(6), 675–694. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-6963(01)00066-3

Danguche, I., & Taifa, I. W. R. (2023). Factors Influencing Total Productive Maintenance Implementation for Thermal Generation Plants. Tanzania Journal of Engineering and Technology, 42(1), 97–112 https://journals.udsm.ac.tz/index.php/tjet/article/view/9156

Díaz-Reza, J. R., García-Alcaraz, J. L., Figueroa, L. J. M., Vidal, R. P., & Muro, J. C. S. D. (2022). Relationship between lean manufacturing tools and their sustainable economic benefits. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, (123), 1269–1284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-022-10208-0

Gelaw, M. T., Azene, D. K., & Berhan, E. (2024). Assessment of critical success factors, barriers and initiatives of total productive maintenance (TPM) in selected Ethiopian manufacturing industries. Journal of Quality in Maintenance Engineering, 30(1), 51–80. https://doi.org/10.1108/JQME-11-2022-0073

Hair, J., & Alamer, A. (2022). Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) in second language and education research: Guidelines using an applied example. Research Methods in Applied Linguistics, 1(3), 100027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmal.2022.100027

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least Squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage.

Hallioui, A., Herrou, B., Katina, P. F., Santos, R. S., Egbue, O., Jasiulewicz-Kaczmarek, M., Soares, J. M., & Marques, P. C. (2023). A review of Sustainable Total Productive Maintenance (STPM). Sustainability, 15(16), 12362. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612362

Kock, N. (2021). WarpPLS user manual: Version 7.0. ScriptWarp Systems.

Kock, N. (2023). Contributing to the success of PLS in SEM: An action research perspective. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 52(1), 730–734. https://aisel.aisnet.org/cais/vol52/iss1/48/

Kock, N., & Hadaya, P. (2018). Minimum sample size estimation in PLS-SEM: The inverse square root and gamma-exponential methods. Information Systems Journal, 28(1), 227–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12131

Koteswarapavan, C., & Pattanaik, L. N. (2024). A novel tool-input-process-output (TIPO) framework for upgrading to lean 4.0. International Journal of Production Management and Engineering, 12(1), 65–77. https://doi.org/10.4995/ijpme.2024.19723

Martínez-Loya, V., Díaz-Reza, J. R., García-Alcaraz, J. L., & Tapia-Coronado, J. Y. (2018). SEM: A global technique—Case applied to TPM. In J. L. García-Alcaraz, G. Alor-Hernández, A. A. Maldonado-Macías, & C. Sánchez-Ramírez (Eds.), New perspectives on applied industrial tools and techniques (pp. 3–22). Springer International Publishing.

Mendes, D., Gaspar, P. D., Charrua-Santos, F., & Navas, H. V. G. (2023). Integrating TPM and Industry 4.0 to increase the availability of industrial assets: A case sttudy on a conveyor belt. Processes, 11(7), 1956. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr11071956

Nakajima, S. (1989). TPM development program: Implementing total productive maintenance. Productivity Press.

Oroye, O. A., Sylvester, B. O., & Farayibi, P. K. (2022). Total productive maintenance and companies performance: A case study of fast moving consumer goods companies. Jurnal Sistem dan Manajemen Industri, 6(1), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.30656/jsmi.v6i1.4185

Parsazadeh, N., Ali, R., Rezaei, M., & Tehrani, S. Z. (2018). The construction and validation of a usability evaluation survey for mobile learning environments. Studies in Educational Evaluation, (58), 97–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2018.06.002

Pascal, V., Toufik, A., Manuel, A., Florent, D., & Frédéric, K. (2019). Improvement indicators for total productive maintenance policy. Control Engineering Practice, (82), 86–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conengprac.2018.09.019

Pramod, V. R., Devadasan, S. R., & Jagathy Raj, V. P. (2010). Quality improvement in engineering education through the synergy of TPM and QFD. International Journal of Management in Education, 4(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMIE.2010.029879

Quiroz-Flores, J. C., & Vega-Alvites, M. L. (2022). Review lean manufacturing model of production management under the preventive maintenance approach to improve efficiency in plastics industry SMES: A case study. South African Journal of Industrial Engineering, 33(2), 143–156. https://doi.org/10.7166/33-2-2711

Rada, E. C., Nicolae, I., Zerbes, M.-V., Tulbure, A., Karaeva, A., Torretta, V., & Giurea, R. (2024). Implementation of a performance management system for environmental sustainability in an industrial organization. Journal of Physics Conference Series, 2857(1), 012030. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/2857/1/012030

Samadhiya, A., Agrawal, R., Kumar, A., & Garza?Reyes, J. A. (2023). Blockchain technology and circular economy in the environment of total productive maintenance: A natural resource-based view perspective. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 34(2), 293–314. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMTM-08-2022-0299

Shingo, S., & Dillon, A. (1989). A study of the Toyota Production System: From an industrial engineering viewpoint (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315136509

Tamás, P., Tollár, S., Illés, B., Bányai, T., Tóth, Á. B., & Skapinyecz, R. (2020). Decision support simulation method for process improvement of electronic product testing systems. Sustainability, 12(7), 3063. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12073063

Valverde-Curi, H., De-La-Cruz-Angles, A., Cano-Lazarte, M., Alvarez, J. M., & Raymundo-Ibañez, C. (2019). Lean management model for waste reduction in the production area of a food processing and preservation SME. In The 5th International Conference Proceeding on Industrial and Business Engineering. https://doi.org/10.1145/3364335.3364378

Womack, J. P., Jones, D., & Ross, D. (2017). La máquina que cambió el mundo: la historia de la producción lean, el arma secreta de Toyota que revolucionó la industria mundial del automóvil. Profit.

Zhang, X. Z. & Chin, J. F. (2021). Implementing total productive maintenance in a manufacturing small or medium-sized enterprise. Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management, 14(2), 152. https://doi.org/10.3926/jiem.3286

Zhou, Z. R., Xiong, X. Q., Wang, J. X., & Bai, H. T. (2022). Equipment management of customized furnishing manufacturers based on total productive maintenance. Chinese Journal of Wood Science and Technology, 36(3), 20–25. https://dx.doi.org/10.12326/j.2096-9694.2021169