BIOENERGY VALORIZATION OF BANANA PEEL WASTE

THROUGH ENZYMATIC HYDROLYSIS: A CIRCULAR

ECONOMY CASE IN MACHALA, ECUADOR

Hugo Romero Bonilla*

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7846-0512

Grupo de Investigación de Aplicaciones Electroanalíticas y Bioenergía, Universidad Técnica de Machala, Ecuador

Cristian Vega Quezada

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7525-2486

Grupo de Investigación de Aplicaciones Electroanalíticas y Bioenergía, Universidad Técnica de Machala, Ecuador

Edgar Tinoco Galvez

https://orcid.org/0009-0007-2920-0152

Grupo de Investigación de Aplicaciones Electroanalíticas y Bioenergía, Universidad Técnica de Machala, Ecuador

Cristopher Choez Tobo

https://orcid.org/0009-0004-5761-6161

Grupo de Investigación de Aplicaciones Electroanalíticas y Bioenergía, Universidad Técnica de Machala, Ecuador

Received: June 12, 2025 / Accepted: August 16, 2025

Published: December 19, 2025

doi: https://doi.org/10.26439/ing.ind2025.n049.7991

This research received no external funding.

* Corresponding author

Author e-mails in order of appearance: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]

This is an open access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence.

ABSTRACT. Researchers utilized an anaerobic reactor to estimate the reduction of CO₂ emissions in Machala, Ecuador, through the enzymatic hydrolysis of mature banana peels. With a weight-to-volume ratio of 60 %, the researchers achieved an estimated reduction of 37,419 t CO₂/year (102,45 t/day), with a purity of 99,97 %. This research supports a circular economy approach, projecting annual carbon credit incentives of 2813,2 dollars from glucose syrup production, with even greater potential returns if the process is expanded to include bioethanol production. The hydrolysis process yielded 5,91 g⋅L-1 of glucose syrup. Furthermore, the bioeconomic potential of the resulting biogas is estimated between 21 and 24 million dollars, necessitating an initial investment of 2,5 to 2,6 million dollars. The absence of public financing incentives restricts private sector implementation. In contrast, producing bioethanol proves to be less profitable, especially when banana peels are used for generating biogas for electricity production.

KEYWORDS: banana / hydrolysis / enzymes / biogas / circular economy / carbon bonds

VALORIZACIÓN BIOENERGÉTICA DE LOS RESIDUOS

DE CÁSCARA DE BANANO MEDIANTE HIDRÓLISIS ENZIMÁTICA:

UN CASO DE ECONOMÍA CIRCULAR EN MACHALA, ECUADOR

RESUMEN. Se utilizó un reactor anaeróbico para estimar la reducción de emisiones de CO₂ en Machala, Ecuador, mediante la hidrólisis enzimática de cáscaras de banano maduras. Con una relación peso/volumen de 60 %, se logró una reducción estimada de 37,419 t CO₂ /año (102,45 t/día), con una pureza del 99,97 %. Esto respalda un enfoque de economía circular, que podría generar incentivos por bonos de carbono de 2813,2 dólares anuales si se produce jarabe de glucosa, y más aún si se extiende a bioetanol. La hidrólisis produjo 5,91 g⋅L-1 de jarabe de glucosa. El potencial bioeconómico del biogás generado se estima entre 21 y 24 millones de dólares, con una inversión inicial de 2,5 a 2,6 millones de dólares. No obstante, la falta de incentivos públicos limita su implementación privada. Comparativamente, la producción de bioetanol resulta menos rentable que la del biogás, especialmente si se destina a generación eléctrica.

PALABRAS CLAVE: plátanos / hidrólisis / enzimas / biogás / economía circular / bonos de carbono

INTRODUCTION

A substantial portion of household and commercial waste consists of organic or biodegradable materials (57 %), including food scraps, yard trimmings, and other degradable matter collectively categorized as Biodegradable Municipal Waste (BMW) (Cardenas Astudillo et al., 2022). Furthermore, waste generated by the food industry and related sectors constitutes a significant segment of BMW (Allegue et al., 2020), with a considerable amount consisting of fruit and vegetable peels (Mittal & Sharma, 2024).

Lignocellulosic residues from banana plants, such as rachis, pseudostems, peels, and leaves, offer significant potential for producing second-generation biofuels, including bioethanol and biogas. A recent study in Ecuador assessed the biomass generation potential in key banana-producing provinces, notably El Oro. The researchers reported a residue-to-product ratio of approximately 3,8, estimating that Ecuador generates around 2,65 million tonnes of dry banana residual biomass annually. In El Oro, researchers measured an average carbon stock of 5,13 megagrams per hectare and estimated the carbon abatement potential to be approximately 3,92 million tonnes of carbon dioxide per year. These findings indicate a significant availability of untapped lignocellulosic feedstock for sustainable energy valorization in the region (Ortiz-Ulloa et al., 2021).

El Oro province encompasses approximately 36,254 hectares (ha) of banana plantations that primarily focus on exportation (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos [INEC], 2024). In addition to serving export markets, local banana production fulfills domestic consumption needs and supplies essential raw materials for the agri-food industry. Several companies in the region specialize in transforming mature banana pulp into flour, puree, and nectar.

Globally, researchers estimate that producers cultivate approximately 114 million metric tonnes of bananas each year. Notably the peel constitutes about 30-40 % of the banana’s weight, a substantial portion that the food industry commonly discards as waste (Putra et al., 2022). In 2023, the Continuous Agricultural Area and Production Survey (ESPAC) reported that the province of El Oro in Ecuador generated around 1,48 million metric tonnes of bananas, thereby establishing itself as one of the country’s primary banana-producing regions (INEC, 2024). These discarded peels undergo natural aerobic fermentation, which leads to the emission of greenhouse gases (GHGs), including methane (CH4), carbon dioxide (CO2), and others.

Enzymatic hydrolysis of banana peels serves as an effective strategy for transforming lignocellulosic waste into fermentable sugars that can be used to produce bioethanol or biogas. By employing enzymes such as cellulase, this process avoids the intensive use of harsh chemicals and high temperatures, thereby reducing energy consumption and emissions compared to traditional industrial methods. Research demonstrates that, after an adequate pretreatment stage, enzymatic hydrolysis achieves high yields of reducing sugars, thereby enhancing ethanol production during fermentation processes (Jennita Jacqueline & Velvizhi, 2024). By converting organic waste into renewable energy, this approach mitigates the need for landfill disposal, which would otherwise result in the generation of greenhouse gases such as methane. This valorization of energy directly contributes to reducing net carbon emissions, aligning with the principles of a circular economy and promoting environmental sustainability (Alzate Acevedo et al., 2021).

Converting banana peel waste into renewable energy prevents its disposal in landfills, where anaerobic decomposition would generate methane. Instead, this model recovers energy through technologies such as microbial fuel cells and anaerobic digestion. This approach enhances resource efficiency, reduces net carbon emissions, and fully embodies the principles of the circular economy (Rincón-Catalán et al., 2022).

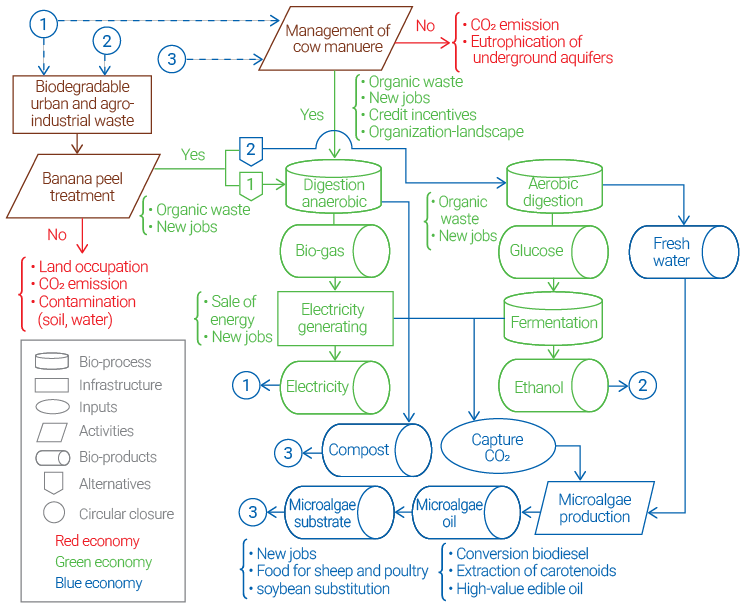

The model highlights the interaction between urban, agro-industrial, and livestock waste streams by reframing biodegradable residues as valuable resources. By drawing on the Chinese circular economy approach, it emphasizes a multilevel strategy: promoting cleaner production at the micro level, fostering industrial symbiosis at the meso level, and advocating for supportive public policies at the macro level.

In this context, the valorization of banana peels in Machala illustrates how local bioenergy initiatives align with the overarching objectives of resource efficiency and sustainable development. The model incorporates a color-coding system: Red, representing the “red economy”, signifies the non-treatment of biodegradable waste. Green, associated with the “green economy”, indicates the treatment of biodegradable waste and includes two environmentally viable alternatives for second-generation biofuel production, while recognizing certain limitations in their profitability when biofuels serve as the sole product or activity. Finally, blue is related to the “blue economy” and encompasses supplementary activities that utilize inputs from previous processes to produce goods that benefit the agro-industry and livestock production, thereby completing a virtuous circle. This approach capitalizes on biotechnological synergies, generating systemic benefits that would not emerge independently among the activities within the framework.

Among the identified alternatives for banana peel utilization, two options have emerged: the production of biogas for electricity generation and the production of ethanol as a biofuel. Adopting an integrated approach that considers economic, environmental, and social dimensions, such as poverty reduction and carbon emissions, researchers assess bioenergy systems using tools like cost-benefit analysis, CO₂-equivalent emission evaluations, and multicriteria decision analysis (Vega Quezada, 2018). Furthermore, incorporating CO₂ capture serves as a critical input for the production of microalgae and their associated by-products.

This integrated approach enables a quantitative assessment of environmental, economic, and social indicators within our proposed circular scheme that utilizes mature banana peels. The primary focus of this study lies in economically quantifying the environmental benefits derived from biogas and ethanol production. To evaluate the biotechnological potential, the researchers conducted an experimental assessment of greenhouse gas GHG emissions from banana peels and their conversion into glucose. This assessment will be supported by estimations of glucose into ethanol, as documented in the existing literature.

Figure 1 illustrates a comprehensive process flow diagram for the proposed circular model, which actively valorizes specific organic wastes, including cow manure and banana peels, as well as other biodegradable urban and agro-industrial waste.

Figure 1

Summary of the process flow for the proposed circular model

METHODOLOGY

Assessment of the bio-economic potential of mature banana peel

This study employs specific methodological tools to establish the bio-economic potential of the banana peel, which are detailed below:

Biogas production

To assess biogas production derived from the anaerobic digestion of urban and agro-industrial biodegradable waste, including livestock manure, it was essential to identify the equivalent CO2 emissions associated with the livestock inventory. This evaluation is associated with livestock inventory. This evaluation utilized the methodology set forth by the Environmental Protection Agency (US Environmental Protection Agency, 2013), which has been effectively applied in previous studies on circular economy dynamics, as demonstrated by Vega Quezada (2018).

The study determined the CO2 emissions from mature banana peels and estimated biogas production from a combination of husks and livestock manure using experimental methods. Additionally, we estimated electric production levels by analyzing the CH4 percentage per cubic meter in the biogas generated during the experiments.

This study expresses all monetary quantifications in US dollars and evaluates them using a cost-benefit analysis (BCA) based on the net present value criterion. The analysis applies discount rates of 6,48 % and 8,84 % to the monetary flows (Vega Quezada, 2018).

Production of ethanol

The second alternative for utilizing urban and agro-industrial biodegradable waste focuses on the production of ethanol. This approach includes an experimental design phase dedicated to converting biomass into glucose, a thorough literature review on ethanol production from glucose, and an evaluation of the opportunity cost of exchanging CO2 emissions for Certified Emission Reductions (CERs), expressed in US dollars. Researchers executed these evaluations through a cost-benefit analysis (BCA) that incorporates the discount rates as described in the preceding section.

Reactor to store CO2 generated by mature banana peel

The setup utilized a 20-litre plastic tank, commonly used for storing purified water. This tank included an inlet and an outlet valve. To facilitate the substrate’s descent to the bottom of the tank, we positioned a 60 cm long PVC pipe with a diameter of 3/4 inches at the top inlet. Additionally, we placed the outlet valve at the tank’s base to enable the discharge of the generated biogas.

Monitoring the volume of CO2 generated by the mature banana peel

We measured the volume of CO2 generated by the mature banana peel three times a day, using a propylene bag as the sampling system.

Determination of the CO2 concentration produced in the reactor from the residues

of mature banana peel

We conducted on-site analysis of the generated CO2 using a FULI Gas Chromatograph equipped with flame ionization (FID) and thermal conductivity (TCD) detectors, along with a capillary column (Supel-Q PLOT, 30 m × 0,32 mm × 40 Å). We utilized hydrogen as the carrier gas, maintaining the furnace, injector, and flame ionization detector at temperatures of 250 °C, ٢٥٠ °C, and ٣٥٠ °C, respectively. To ensure accuracy, we constructed a calibration curve using CO2 as the reference standard and performed all measurements in duplicate.

Conversion of litres of CO2 to tonnes of CO2 that are no longer emitted

The gas density, measured at 1,96 g⋅L-1, facilitated the calculation of the metric tonnes of CO2 generated from mature banana peel residues.

Determination of the biotechnological potential of mature banana peels

Biotechnological processes such as enzymatic hydrolysis and alcoholic fermentation convert mature banana peels into glucose and bioethanol, with the latter serving as a second-generation biofuel. To optimize both the yield and kinetics of the bioconversion of lignocellulosic residues into biofuels, the inclusion of pretreatment stages proves essential in this biotechnological process.

Pretreatment of grinding + hydroxide for enzymatic hydrolysis

To initiate the lignocellulosic degradation process, we first milled the banana husk and then added 1 % sodium hydroxide to raise the pH to 11. We allowed the biomass to stand for one day. Subsequently, we introduced citric acid until the pH reached 5, which is the optimal pH for effective fungal adaptation during the enzymatic hydrolysis process.

The methodology employed enzymatic hydrolysis using cellulases that convert the cellulose in banana peels into glucose. We utilized the Trichoderma reesei species as the enzyme-producing agent for this transformation. Following pretreatment, we prepared 4 L bioreactors and maintained them at room temperature (28 °C-30 °C) for six days, conducting daily glucose content monitoring. For this purpose, 5 ml of each sample underwent pre-filtration. In accordance with the recommendations of Romero et al (2015), the researchers applied a weight/volume (w/v) ratio of 60 % of lignocellulosic residue to water, resulting in a total substrate volume of 2 L (biomass). They subjected this substrate to enzymatic hydrolysis with Trichoderma reesei at a concentration of 0,6 g⋅L-1 (w/v). Before enzymatic hydrolysis, manual agitation ensured the even distribution of cellulase enzymes, which are crucial for converting cellulose into glucose.

RESULTS

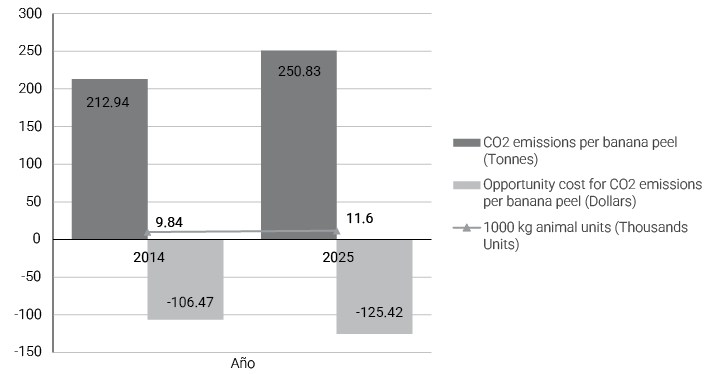

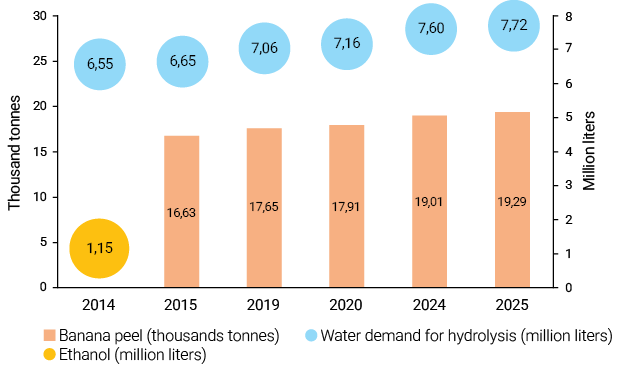

This analysis investigates the bio-economic potential of converting urban, agro-industrial, and livestock biodegradable waste into biogas, covering the study period from 2014 to 2025. Figure 1 illustrates the byproducts generated from the agro-industrial and livestock sectors. As shown in Figure 2, the estimated volume of banana peels during this period ranges from 16,380 to 19,294 tonnes. Aerobic decomposition of these peels generates CO2 emissions totaling approximately 213 to 251 tonnes across the study horizon.

The analysis presents the equivalent monetary value of mitigating CO2 emissions from banana peels. It highlights that these potential monetary benefits, arising from CO2 mitigation, represent an opportunity cost since they do not generate income until stakeholders implement mitigation initiatives. An important factor to consider is the necessity of utilizing a specific quantity of 1000 kg cattle units alongside banana peels to effectively execute GHG mitigation strategies within the framework of a circular economy. This approach emphasizes the conversion of biodegradable waste, including both animal and livestock byproducts, into valuable outputs that can support biotechnological processes, such as biogas production for energy purposes, as illustrated in Figure 3 below.

Figure 2

CO2 emissions from the banana peel and the livestock inventory

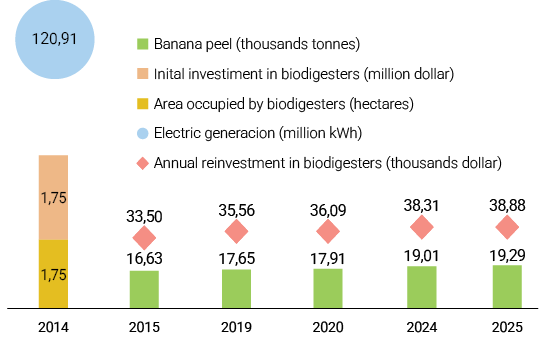

Figure 3 presents estimates for the initial investment required, the expected availability of banana husks, the land area necessary for implementing this initiative, the periodic reinvestment needed to manage the increasing residues, and the projected total electricity generation from biogas combustion over the period of 2014 to 2025.

Figure 3

Investment, revenue, and energy production from the combustion of biogas

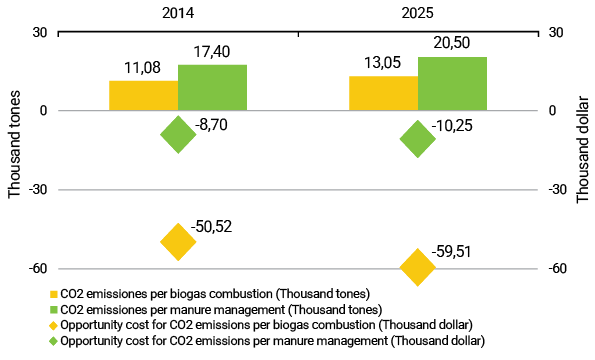

Furthermore, Figure 4 presents the CO2 emissions generated by the combustion of biogas for energy production and by manure management, while accounting for the changes in biogas production throughout the study period. Notably, the emissions from biogas combustion exceed the equivalent CO2 emissions from manure management in the livestock sector.

Figure 4

CO2 emissions and opportunity cost in biogas combustion and manure management

Table 1 summarizes the economic, environmental, and social indicators associated with the implementation of the biogas production initiative for energy purposes. This initiative estimates a Net Present Value (NPV) between 23,71 to 20,67 million dollars. While the initiative may initially appear economically unviable when focused solely on electricity generation, the circular flow of by-products for agro-productive purposes, such as fertilizers, reveals the systemic effects of the proposed scheme. By capitalizing on potential revenue from by-products and transforming the opportunity costs of environmental liabilities into income through mitigation, the initiative yields significant monetary benefits, ranging from 125,94 and 110,89 thousand dollars. This initiative also aims to reduce approximately 374 thousand tonnes of CO2 emissions and has the potential to create a positive socio-economic impact at the local level, directly employing 3508 households.

Table 1

Assessing economic, environmental, and social indicators of biogas production from agro-industrial and livestock waste within a circular economy

|

Biogas |

Discount rate (k) |

Unit |

||

|

6,48 % |

8,84 % |

|||

|

Economic indicators |

(+) Electricity sales revenue |

2,8 |

2,48 |

million dollars |

|

(-) Biodigester + Electric generators |

2,62 |

2,54 |

million dollars |

|

|

(-) Labor cost |

156,86 |

138,12 |

million dollars |

|

|

(+) Liquid fertilizer |

150,98 |

132,94 |

million dollars |

|

|

(+) Solid fertilizer |

29,41 |

25,9 |

million dollars |

|

|

(=) NPV |

23,71 |

20,67 |

million dollars |

|

|

Opportunity cost |

||||

|

(+/-) CO₂ emissions - Banana peel |

0,93 |

0,82 |

thousand dollars |

|

|

(+/-) CO₂ emissions - Manure management |

76,37 |

67,25 |

thousand dollars |

|

|

(+/-) CO₂ emissions - Biogas combustion |

48,63 |

42,82 |

thousand dollars |

|

|

(=) NPV |

125,94 |

110,89 |

thousand dollars |

|

|

Environmental indicators |

CO₂ emissions - Banana peel |

2,78 |

thousand tonnes |

|

|

CO₂ emissions - Manure management |

226,92 |

thousand tonnes |

||

|

CO₂ emissions - Biogas combustion |

144,49 |

thousand tonnes |

||

|

Total CO₂ emissions |

374,19 |

thousand tonnes |

||

|

Social indicators |

New jobs |

3 508 |

people |

|

|

Water requirement |

149,53 |

thousand m³ |

||

The second method for utilizing urban waste, particularly mature banana peels, involves the production of ethanol. Figure 5 depicts the main inputs, products, and by-products generated during the analysis period. This figure highlights the anticipated production of just over 1,15 million litres of ethanol throughout the study period, alongside an estimated water requirement of approximately 85,45 million litres for the enzymatic hydrolysis process used to obtain glucose.

Figure 5

Main inputs and by-products in the production of ethanol from banana peels

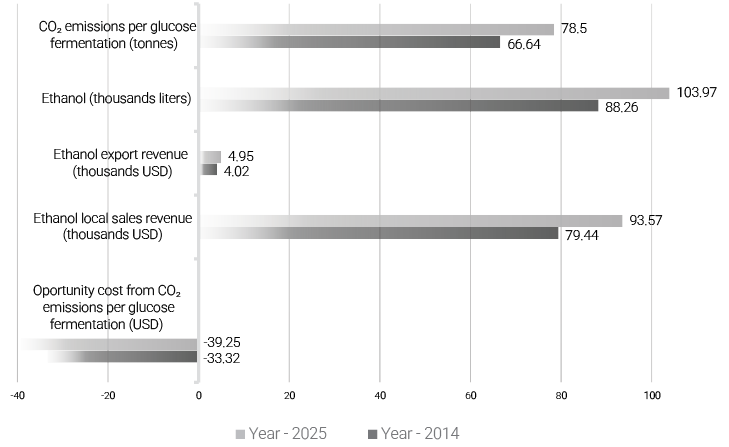

Figure 6 illustrates the progression of CO2 emissions resulting from the glucose fermentation process, while concurrently highlighting the opportunity cost linked to CO2 emissions from the decomposition of banana peels. This figure also details the evolving potential revenues from ethanol sales under two distinct trade scenarios. The first scenario estimates earnings derived from exporting ethanol at international prices (OECD/FAO, 2016), whereas the second quantifies revenue generated from local ethanol sales, taking into account incentives for domestic biofuel production in Ecuador.

Figure 6

CO2 emissions and opportunity cost in ethanol production

The analysis of economic, environmental, and social indicators related to the utilization of biodegradable municipal waste in ethanol production reveals significant contrasts in potential revenues from ethanol sales between the global and local markets, as illustrated in Table 2. However, researchers were unable to quantify the costs associated with the investment and operational aspects of ethanol production due to limitations in the available official literature during the study period. Estimates indicate that CO2 emissions from ethanol production totaled 3,65 thousand tonnes. Furthermore, the estimated opportunity costs and potential monetary benefits of initiatives aimed at reducing CO2 emissions range from 1,08 to 1,23 thousand dollars.

Table 2

Economic, environmental and social indicators of agro-industrial waste use in ethanol production under the circular economy approach

|

Ethanol |

Discount rate (k) |

Unit |

||

|

6,48 % |

8,84 % |

|||

|

Economic indicators |

(+) Ethanol sales revenue – |

33,09 |

29,07 |

thousands of dollars |

|

(+) Ethanol sales revenue – |

697,34 |

614,02 |

thousands of dollars |

|

|

(-) Investment and labor cost |

N/A |

N/A |

thousands of dollars |

|

|

Opportunity cost |

||||

|

(+/-) CO₂ emissions – |

0,93 |

0,82 |

thousands of dollars |

|

|

(+/-) CO₂ emissions – |

0,29 |

0,26 |

thousands of dollars |

|

|

(=) NPV (Net Present Value) |

1,23 |

1,08 |

thousands of dollars |

|

|

Environmental |

CO₂ emissions – |

2,78 |

thousand tonnes |

|

|

CO₂ emissions – |

0,87 |

thousand tonnes |

||

|

Total CO₂ emissions |

3,65 |

thousand tonnes |

||

|

Social indicators |

New jobs |

N/A |

People |

|

|

Residual fresh water |

170,89 |

thousand m³ |

||

DISCUSSION

Glucose concentrations in the syrup reached a mean of approximately 5 g⋅L-1 by the sixth day of experimentation. This result aligns with the findings of other researchers, such as Abdulla et al. (2022), who reported values of 5,31 g⋅L-1, and Indulekha et al. (2020) who found 4,24 g⋅L-1 for the enzymatic hydrolysis of dried banana peels—a process that inherently involves higher pretreatment costs. While earlier studies focused on optimizing sugar yields using dried peel inputs with a response surface methodology, our findings highlight the sensitivity of yield to pretreatment methods because they are derived from undried substrate conditions. Furthermore, they show the potential trade-off between cost and enzymatic efficiency.

Conversely, producing biogas from this residue demonstrates a substantial bioeconomic potential, estimated at between 21 and 24 million dollars annually. However, this potential depends on an initial investment of approximately 2,5 to 2,6 million dollars. In the absence of public funding incentives, this economic barrier presents a significant challenge for private sector adoption.

In contrast, ethanol production has demonstrated lower profitability. Its economic viability relies heavily on state support through various incentives and regulatory frameworks. Brazil serves as a prominent example, where long-term policies have successfully driven the expansion of the ethanol market. Specifically, the production of flex-fuel vehicles surged from 49,264 units in 2003 to over 2,95 million units in 2013, thereby consolidating a robust domestic market for this biofuel (Karp et al., 2021). As of 2023, Brazil holds the position of the second-largest ethanol producer globally, generating 32,95 billion litres, which constitutes approximately 30 % of total global production (Hayashi, 2024). In 2018, ethanol represented 6,4 % of the country’s overall energy consumption (Karp et al., 2021).

The Brazilian government implemented the RenovaBio program in 2017, playing a pivotal role in decarbonizing the energy sector. In 2022, the program succeeded in avoiding 71,1 million metric tonnes of CO₂ equivalent and aims to achieve a cumulative reduction of 678 million metric tonnes by 2030 (Hayashi, 2024).

While ethanol supports climate goals and aligns with Sustainable Development Goal 7 (SDG7), its adoption in Brazil remains inconsistent due to seasonal competitiveness and regional disparities. Forecasts suggest that gasoline will continue to dominate fuel consumption through 2030, highlighting the challenges of shifting consumer behavior and market dynamics toward renewable alternatives (Marques Serrano et al., 2025).

The data strongly indicate that in developing countries like Ecuador, implementing robust public policies aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) could enhance the viability of ethanol production from agricultural waste. In the absence of such policies, this study reveals that biogas production presents a more profitable and readily implementable alternative.

CONCLUSIONS

The implementation of this initiative in the city of Machala, Ecuador, could prevent the emission of approximately 374,19 thousand tonnes of CO₂ over the designated time horizon, achieving a capture purity of 99,97 %. This reduction underscores the environmental significance of the proposed bioethanol production scheme, especially in urban areas facing increasing energy demands and sustainability challenges.

The bioeconomic potential of ethanol production is contingent on keeping production costs below the projected revenue range, estimated to be between USD 614 000 and 698 000. During the study period, the anticipated output exceeded 1,15 million litres of ethanol. This production process requires approximately 85,45 million litres of water, primarily for the enzymatic hydrolysis stage, which is essential for glucose generation. These figures highlight the importance of resource efficiency and process optimization in achieving long-term economic viability.

The initiative, while initially perceived as economically unviable when evaluated solely for electricity generation, reveals its true potential through the integration of by-products into agro-productive systems. By-products, such as organic fertilizers, generate additional revenue streams and underscore the broader systemic effects of the project. Current estimates suggest that the monetary gains from these by-products, along with the conversion of environmental liability costs into productive income, will range between USD 110 890 and 125 940. Furthermore, the initiative is expected to reduce approximately 374 000 tonnes of CO₂ emissions throughout its operational period. In addition to its environmental advantages, the project provides significant socio-economic advantages, directly employing around 3 508 households, thereby making a meaningful contribution to local development and social inclusion.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

CREDIT AUTHOR STATEMENT

Hugo Romero Bonilla: conceptualization, secured funding, research methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, writing: original draft. Cristhian Vega Quezada: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, research, methodology, project administration, software, visualization. Edgar Tinoco Galvez: Formal analysis, methodology, software, validation, visualization. Cristopher Manuel Choez Tobo: investigation, visualization, writing: original draft, writing: review & editing.

REFERENCES

Abdulla, R., Johnny, Q., Jawan, R., & Sani, S. A. (2022). Agrowastes of banana peels as an eco-friendly feedstock for the production of biofuels using immobilized yeast cells. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 1103(1), 012022. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/1103/1/012022

Allegue, L. D., Puyol, D., & Melero, J. A. (2020). Food waste valorization by purple phototrophic bacteria and anaerobic digestion after thermal hydrolysis. Biomass and Bioenergy, 142, 105803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2020.105803

Alzate Acevedo, S., Díaz Carrillo, Á. J., Flórez-López, E., & Grande-Tovar, C. (2021). Recovery of banana waste-loss from production and processing: A contribution to a circular economy. Molecules, 26(17), 5282. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26175282

Cardenas Astudillo, A. J., Vásquez Vera, M. M., Vera Bravo, M. L., Villamil Valencia, I. A., & Calderón Pincay, J. M. (2022). Origen y composición de los residuos sólidos en la ciudad de Calceta, Manabí. Revista ESPAMCIENCIA, 13(2), 62-65. https://doi.org/10.51260/revista_espamciencia.v13i2.311

Hayashi, T. (2024). Brazil biofuels annual report 2024. GAIN Report BR2024-0022. https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=Biofuels+Annual_Brasilia_Brazil_BR2024-0022.pdf

Indulekha, J., Prasanthi, Y., & Arunagiri, A. (2020). Production of bioethanol from banana peel using isolated cellulase from Aspergillus Niger. En Global challenges in energy and environment: Select proceedings of ICEE 2018 (pp. 9-18). Lecture Notes on Multidisciplinary Industrial Engineering. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-9213-9_2

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos. (2024). Encuesta de superficie y producción agropecuaria continua - ESPAC 2023. https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/documentos/web-inec/Estadisticas_agropecuarias/espac/2023/Principales_resultados_ESPAC_2023.pdf

Jennita Jacqueline, P., & Velvizhi, G. (2024). Co-fermentation exploiting glucose and xylose utilizing thermotolerant S. cerevisiae of highly lignified biomass for biofuel production: Statistical optimization and kinetic models. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology, 58, 103197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcab.2024.103197

Karp, S. G., Medina, J. D. C., Letti, L. A. J., Woiciechowski, A. L., Carvalho, J. C., Schmitt, C. C., Penha, R. O., Kumlehn, G. S., & Soccol, C. R. (2021). Bioeconomy and biofuels: The case of sugarcane ethanol in Brazil. Biofuels, Bioproducts and Biorefining, 15(3), 899-912. https://doi.org/10.1002/bbb.2195

Marques Serrano, A., dos Santos Martins, P., Vergara, G., Bispo, G., Pimenta, G., Rezende, L., Noschang, M., Neumann, C., Mendonça, M., & Pereira, V. (2025). Forecasting ethanol and gasoline consumption in Brazil: Advanced temporal models for sustainable energy management. Energies, 18(6), 1501. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18061501

Mittal, V., & Sharma, A. (2024). From scraps to solutions: Harnessing the potential of vegetable and fruit waste in pharmaceutical formulations. Letters in Functional Foods, 1, Artículo e230124225963. https://doi.org/10.2174/0126669390271001231122051310

OECD/FAO. (2016). OECD-FAO agricultural outlook 2016-2025. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/agr_outlook-2016-en

Ortiz-Ulloa, J. A., Abril-González, M. F., Pelaez-Samaniego, M. R., & Zalamea-Piedra, T. S. (2021). Biomass yield and carbon abatement potential of banana crops (Musa spp.) in Ecuador. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28(15), 18741-18753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-09755-4

Putra, N. R., Aziz, A. H. A., Faizal, A. N. M., & Che Yunus, M. A. (2022). Methods and potential in valorization of banana peels waste by various extraction processes: In review. Sustainability, 14(17), 10571. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710571

Rincón-Catalán, N. I., Cruz-Salomón, A., Sebastian, P. J., Pérez-Fabiel, S., Hernández-Cruz, M. d. C., Sánchez-Albores, R. M., Hernández-Méndez, J. M. E., Domínguez-Espinosa, M. E., Esquinca-Avilés, H. A., Ríos-Valdovinos, E. I., & Nájera-Aguilar, H. A. (2022). Banana waste-to-energy valorization by microbial fuel cell coupled with anaerobic digestion. Processes, 10(8), 1552. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr10081552

Romero, H., Ayala, H., & Lapo, B. (2015). Effect of three pre-treatments of banana peel for obtaining glucose syrup by enzymatic hydrolysis. Advances in Chemistry, 10(1), 79-82. http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=85018761402&partnerID=8YFLogxK

US Environmental Protection Agency. (2013). Inventory of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions and sinks: 1990-2011. https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/inventory-us-greenhouse-gas-emissions-and-sinks-1990-2011

Vega Quezada, C. A. (2018). Sinergias entre agricultura y bioenergía como estrategia de desarrollo desde los bordes en los países de América Latina: caso de frontera entre Ecuador y Perú [Doctoral Dissertation, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid]. Archivo Digital, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. https://doi.org/10.20868/UPM.thesis.53164